What’s the Deal With Greenland?

A collaboration between Lewis McLain & AI

In December of 1966, I was at the end of basic training at Lackland in San Antonio. We were days away from being shipped to our selected fields of training. The memories of early days of basic training where the Staff Sargent stood 6 inches from your face and yelled at you were faintly going away. Even Sargent Sharp’s demeanor had changed. We had been transformed under his leadership. There was even a tinge of humor in his voice. Sometimes.

Our squad leader had somehow learned we were Sgt Sharp’s last group to train. He as being shipped to Thule Greenland. On the last day our squad leader made up a chant about Thule. Sgt Sharp was in another building with his peers while we were taking a break. In perfect formation, we marched by the building screaming out the chant. After we passed, we turned around and went by the barracks again. This time Sgt Sharp came out of the building, looking tough with his hands on his hips. Then he burst out in laughter. It was a great moment.

I had not heard the words “Thule Greenland” in over 60 years until it came up in the news recently. So,

I decided to gain a better understanding of this story on my own and share it with you today. LFM

Ice, power, restraint — and what a U.S. president can actually do

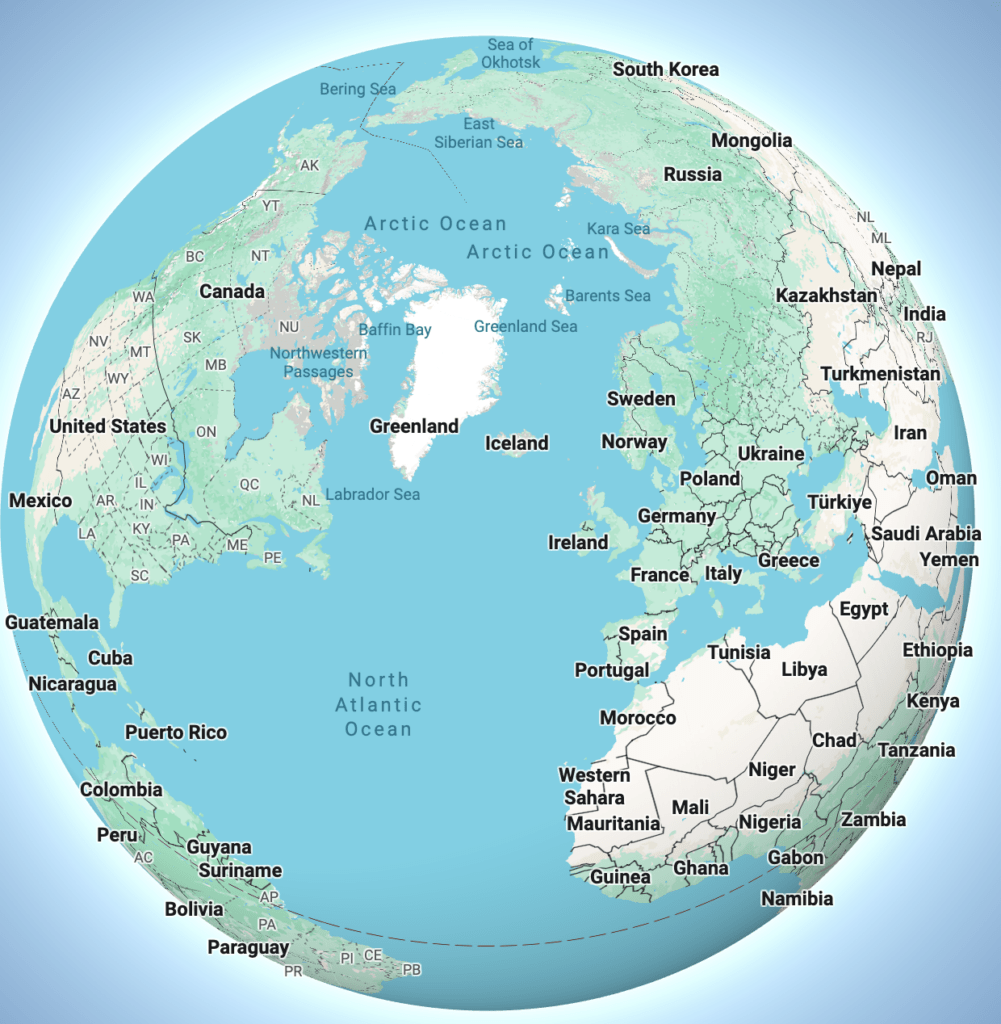

Greenland looks empty on a map. White space. Edge-of-the-world quiet. That appearance is deceptive. Greenland is one of those places where geography speaks in a low voice that never shuts up. It sits between North America and Europe, under the polar routes that matter for missiles, satellites, and future shipping, and adjacent to the ambitions of Russia and China.

That is why it keeps resurfacing in American politics — including under Donald Trump. And to understand why his options are narrower than his rhetoric, you have to understand Greenland whole.

History in brief: autonomy, not absence

Greenland has been home to Inuit peoples for millennia. Norse settlers arrived around 1000 AD and vanished. Danish administration followed centuries later, eventually folding Greenland into the Kingdom of Denmark.

In the modern era, Greenland steadily pulled authority inward:

- 1979: Home Rule

- 2009: Self-Government

Greenland now controls its internal affairs, culture, language, and economy. Denmark retains defense and foreign policy, but Greenland is no passive appendage. It has a parliament, a national identity, and a long memory of being spoken about rather than with.

Why the U.S. showed up — and stayed

The U.S. arrived during World War II after Nazi Germany occupied Denmark. Greenland could not defend itself. America stepped in to prevent German control of the North Atlantic and Arctic approaches.

The Cold War turned that necessity into permanence. At the center stood Thule Air Base — now Pituffik Space Base — positioned to watch the polar routes where Soviet missiles would fly. Greenland became a shield, not a launchpad.

At the Cold War peak (late 1950s–early 1960s):

- ~10,000 U.S. personnel

- A full military town

- Central to missile warning and Strategic Air Command planning

Today, that footprint is lean: roughly 150–200 U.S. service members, focused on missile warning, space surveillance, and Arctic operations. Fewer people. More precision. Higher stakes.

Why it was called Thule

“Thule” comes from classical antiquity — Ultima Thule, the farthest place imaginable, beyond the edge of the known world. Greek and Roman writers used it as shorthand for the extreme north, where maps dissolved into myth.

The Cold War base inherited the name because it sat beyond precedent: remote, polar, and strategically singular. Its renaming to Pituffik — the Greenlandic place name — reflects a deeper shift. Greenland no longer wants to be a myth on someone else’s map. It wants to be a place with a voice.

Population, oil, electricity: restraint as strategy

Greenland has about 56,000 people, one-third of them in Nuuk, the rest scattered along the coast. There are no inland cities. Ice owns the interior.

That scale explains three major choices:

- Oil: Greenland may sit near offshore hydrocarbon basins, but in 2021 it halted new oil and gas exploration. The risks — environmental, social, political — were judged too large for a tiny population to absorb.

- Electricity: Civilian power is mostly renewable, anchored by hydropower from glacial meltwater. There is no national grid — each town runs its own isolated system. It’s pragmatic, not flashy.

- Military footprint: Greenland resists large permanent forces because scale overwhelms small societies fast.

Across domains, Greenland repeatedly chooses control over speed.

The missing piece: what President Trump can actually do

This is where headlines often outrun reality.

A U.S. president cannot buy Greenland, seize Greenland, or unilaterally expand forces there. Greenland is not U.S. territory, and American presence exists under treaty — especially the 1951 defense agreement with Denmark. Unilateral action would violate law, fracture alliances, and hand Russia and China a propaganda gift.

But that does not mean a president is powerless. Far from it.

Trump’s practical Greenland strategy (not the theatrical one)

1. Renegotiate, don’t bulldoze

Trump can push to update defense agreements with Denmark to reflect:

- New missile threats

- Space-domain competition

- Arctic access and logistics needs

Treaties evolve when threat pictures change — and the Arctic threat picture has changed dramatically.

2. NATO-ize the Arctic

By framing upgrades as NATO requirements rather than unilateral U.S. moves, resistance drops. Denmark gains cover. Greenland hears “alliance defense,” not “American expansion.”

3. Spend money instead of issuing ultimatums

Greenland is small. Targeted U.S. funding for:

- Airports

- Ports

- Communications

- Dual-use infrastructure

can materially change public opinion without changing sovereignty.

Influence scales faster where population is tiny.

4. Crowd out China quietly

China wants Arctic access, minerals, and influence. Trump’s real leverage is negative:

- Export controls

- Financing pressure

- Market access signals

Greenland prefers Western partners. It just doesn’t want to look coerced.

5. Expand incrementally, not dramatically

More rotations, more “temporary” systems, more mission creep — fewer headline announcements. In a society of 56,000 people, shock matters more than numbers.

6. Control the tone

Talking about “buying” Greenland backfires. Talking about partnership works. In small societies, rhetoric is not noise — it’s substance.

Why the map matters

Look again at the Arctic map:

- Greenland sits between the United States and Russia

- China is not Arctic by geography, but is pushing in by economics and science

- Missiles, satellites, and shipping all pass north

Greenland is not a side story. It is a junction.

The real deal

Greenland is not a prize to be claimed. It is a pivot to be managed.

It matters because geography never stopped mattering — even in an age of cyberspace and AI. But Greenland has learned something many places learn too late: once you let scale run away from you, you don’t get control back.

So the deal is this:

The U.S. will always need Greenland.

Russia and China will always want influence there.

And Greenland will continue doing what small, strategically vital societies do best:

Move slowly. Say no often. Trade access for respect.

That isn’t weakness.

That’s survival at the top of the world.

You must be logged in to post a comment.