A collaboration between Lewis McLain & AI

Skills, Motivation, and the Capabilities Behind Accurate Mapping

Introduction: The Human Attempt to Shrink the World Into Understanding

A map seems simple at first glance: a flat surface covered with lines, shapes, labels, and colors. Yet the act of creating an accurate map is one of the most difficult intellectual tasks humans have ever attempted. Mapping demands a rare combination of observation, mathematics, engineering, imagination, artistry, philosophy, and courage. It requires a person to look at a world too large to see all at once and to represent it faithfully on something small enough to hold in the hand. Every map, whether carved on a clay tablet or drawn by satellite algorithms, is a claim about what is real and what matters.

This paper explores the mapmaker’s mind across four eras—ancient, exploratory, philosophical, and modern technological—and then strengthens that understanding through case studies and technical appendices. Throughout the narrative, one idea remains constant: accuracy is not merely a technical achievement; it is a human triumph grounded in the mapmaker’s inner capabilities.

I. Ancient Mapmakers: Building Accuracy from Memory, Observation, and Survival

For thousands of years, before the invention of compasses, sextants, or even numerals as we know them, mapmakers relied on the most fundamental tools available to any human being: their memory, their senses, and their endurance.

A Babylonian cartographer might spend long days walking field boundaries and tying lengths of rope to stakes to re-establish property lines after floods. An Egyptian “rope stretcher” could look at the shadow of a pillar, note the angle, and derive a surprisingly accurate sense of latitude and season. Polynesian navigators sensed the shape of islands from the swell of the ocean, the direction of prevailing winds, the pattern of clouds, or the flight paths of birds—even when land was hundreds of miles away. All of this happened without written language in many places, and without anything like formal mathematics.

The motivations were simple but powerful. Survival required knowing where water, game, shelter, and danger lay. Governance required knowing how much farmland belonged to whom, where the temples held jurisdiction, and how to tax agricultural output. Trade required predictable knowledge of paths, distances, and safe passages. Human curiosity played its own role as well; people have always wanted to know the shape of their world.

Accuracy in ancient mapping was limited by natural constraints. Long distances could not be measured with confidence. Longitude remained elusive for nearly all of human history. Oral traditions, though rich, introduced distortions. Political agendas often shaped borders. And yet ancient maps show remarkable competence: logical river systems, consistent directions, recognizable landforms, and surprisingly stable proportionality. Accuracy was relative to the tools available, but the intent—the desire to record reality—was the same as today.

II. Explorers and Enlightenment Surveyors: Lewis & Clark and the Birth of Scientific Mapping

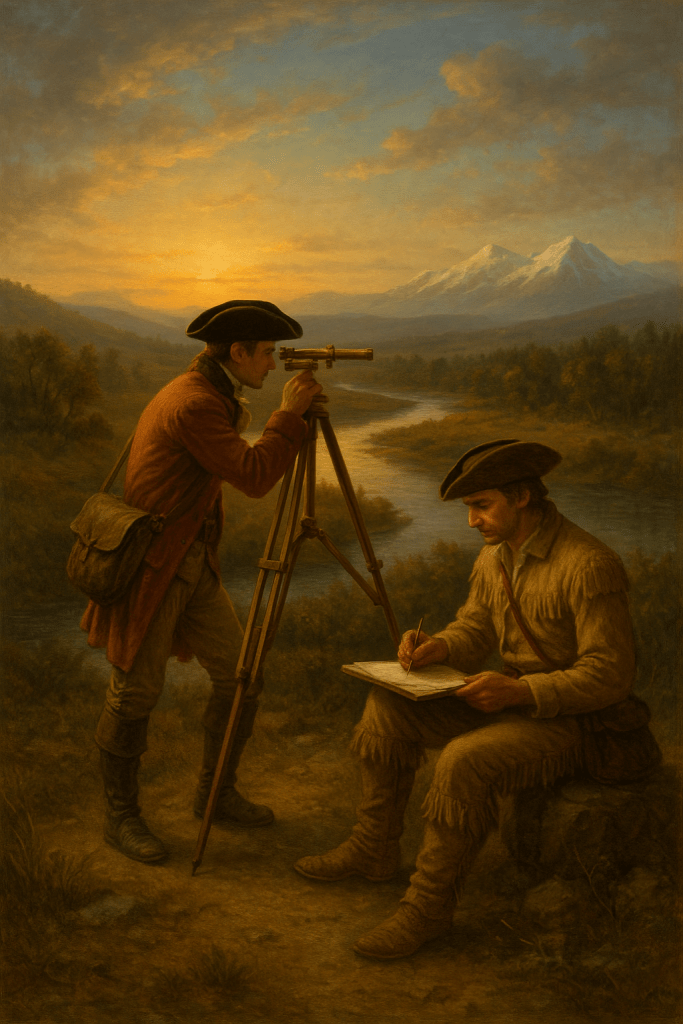

The early nineteenth century introduced a new kind of cartographer: the trained surveyor who combined field observation with scientific measurement. Lewis and Clark exemplify this transition.

Armed with sextants, compasses, chronometers, astronomical tables, and notebooks filled with surveying instructions, they attempted to impose geometric precision on a landscape no European-American had ever mapped. They measured solar angles to determine latitude, recorded compass bearings at virtually every bend of the Missouri River, estimated distances by managing travel speeds, and triangulated mountain peaks whenever weather permitted. Their notebooks reveal how meticulously they checked, recalculated, and corrected their own readings.

Their motivation blended national ambition, Enlightenment science, personal curiosity, and a desire for legacy. President Jefferson viewed the expedition as a grand experiment in empirical observation and hoped to gather geographic, botanical, zoological, and ethnographic knowledge all at once. Lewis and Clark themselves were deeply committed to documenting not only what they saw but how they measured it.

Despite their tools, they faced severe limitations. Cloud cover often prevented celestial readings. Magnetic variation made some compass bearings unreliable. River distances were difficult to estimate accurately when paddling against currents. Longitudes were usually approximations, sometimes guessed, because no portable timekeeping device of the period could maintain accuracy under field conditions. Yet the map produced from their expedition defined the American West for decades, confirmed mountain ranges, captured river systems, located tribal lands, and fundamentally reshaped the geographic understanding of a continent.

Their accomplishment demonstrates that accuracy is a function not only of tools but of discipline, repetition, cross-checking, and the mental fortitude to tolerate error until it can be corrected.

III. The Philosophical Mapmaker: Understanding That a Map Is a Model, Not the World

One of the most difficult but essential truths in cartography is that a map can never be fully accurate in every dimension. A map is a model, not the thing itself. Understanding this transforms how we judge accuracy.

No map can include everything. The mapmaker must decide what to include and what to omit, what to emphasize and what to generalize. This selective process shapes meaning as much as measurement does. A map that focuses on roads sacrifices terrain; a map that shows landforms hides political boundaries; a nautical chart prioritizes depth, hazards, and tides while ignoring nearly everything inland.

Even more fundamentally, the Earth is round and a map is flat. Flattening a sphere introduces distortions in shape, area, distance, or direction. No projection solves all problems at once. The Mercator projection preserves direction for navigation but distorts the sizes of continents dramatically. Equal-area projections preserve proportional land area but contort shapes. Conic projections work beautifully for mid-latitude regions like the United States but fail near the equator and poles.

Scale introduces another layer of philosophical choice. A map of a neighborhood can show driveways, footpaths, and fire hydrants; a map of a nation must erase tens of thousands of such details. At global scale, even major rivers become thin suggestions rather than features.

Finally, maps inevitably carry bias. National borders are often political statements as much as geographic descriptions. Cultural assumptions guide what is considered important. The purpose of a map—a subway map, a floodplain map, a highway atlas—governs its priorities. Every map quietly expresses a worldview.

Thus, “accurate” does not mean “perfectly true.” It means “fit for the purpose.” A map is correct to the extent that it serves the need it was created for.

IV. The Modern Cartographer: Satellites, GIS, and the Era of Precision

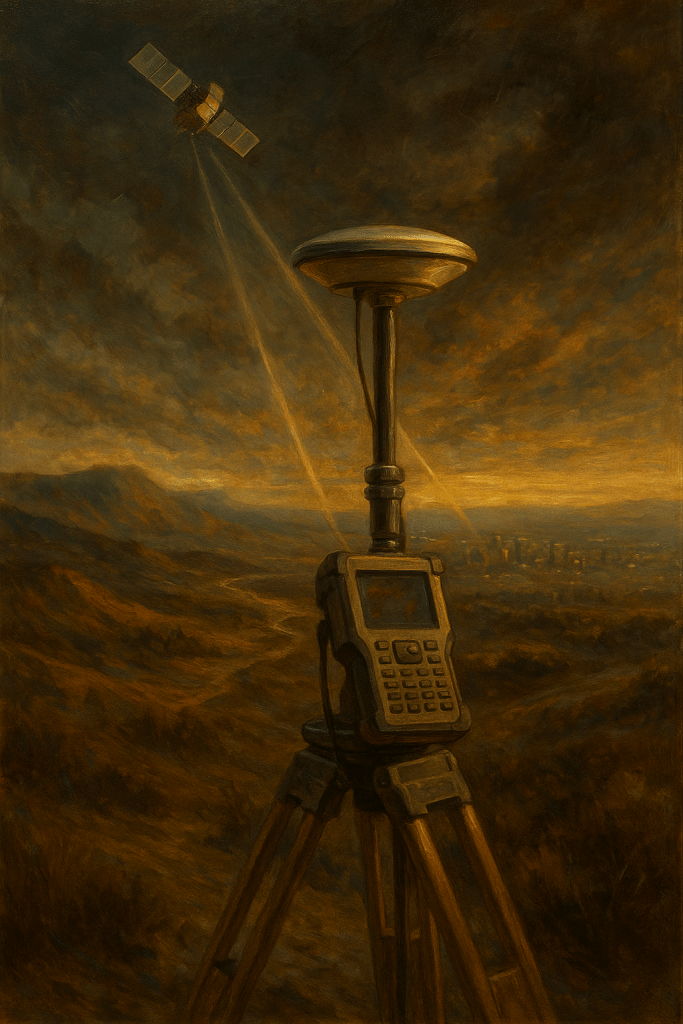

The modern mapmaker operates in a world overflowing with spatial information. GPS satellites circle the earth, constantly broadcasting timing signals that allow any handheld receiver to determine position within a few meters—and survey-grade receivers to reach centimeter-level accuracy. High-resolution satellite imagery captures coastlines, forests, highways, and rooftops with astonishing clarity. LiDAR sensors measure elevation by firing millions of laser pulses per second, creating three-dimensional models of terrain. GIS (Geographic Information Systems) software organizes, analyzes, and visualizes enormous spatial datasets.

The work of the modern cartographer is less about drawing lines and more about managing data. A GIS analyst must understand spatial statistics, database schemas, metadata verification, remote sensing interpretation, coordinate transformations, and the difference between nominal, ordinal, interval, and ratio data. The skill set is analytical, computational, and scientific.

The motivations have expanded as well. Modern mapping supports transportation engineering, zoning, emergency response, flood mitigation, environmental policy, epidemiology, commercial logistics, climate science, and international security. Governments, companies, and researchers all rely on constantly updated maps to make daily decisions.

Yet the abundance of data introduces new complications. Errors no longer stem primarily from lack of information but from inconsistency among datasets, outdated imagery, automated misclassification, incorrect coordinate transformation, or the false sense of precision that digital numbers can give. Even in a world of satellites, the mapmaker must remain vigilant and skeptical. Accuracy must still be earned, not assumed.

V. Case Studies: How Real Maps Achieve Real Accuracy

The theory of mapmaking becomes clearer when examined through specific examples. Four case studies reveal how different contexts produce different solutions to the same universal problem.

Case Study 1: The USGS Topographic Map

The United States Geological Survey began producing standardized topographic maps in the late nineteenth century, combining triangulation, plane-table surveying, and field verification. Later editions incorporated aerial photography and eventually satellite data. These maps formed the spatial backbone of national development. Engineers relied on them to place highways, dams, airports, pipelines, and railroads. Hikers and outdoor enthusiasts still use them today.

Their accuracy was remarkable for their time: often within a few meters horizontally and within a meter vertically. They became the nation’s common spatial language, demonstrating how consistent methodology and repeated verification create reliability across vast geographic space.

Case Study 2: Nautical Charts and the Challenge of the Ocean

No mapping discipline demands more caution than nautical charting. Mariners depend on accurate depths, hazard markings, and tidal information. Early sailors used weighted ropes and visual triangulation to estimate depth. Today’s hydrographers use multibeam sonar, satellite altimetry, LiDAR bathymetry, and tide-corrected measurements to produce charts that can reveal underwater features with astonishing detail.

Yet the ocean floor is dynamic. Storms move sandbars. Currents reshape channels. Dredging alters harbor depths. For this reason, nautical charts are never fully “finished.” They require constant updating. The challenge is not simply measuring depth once, but sustaining accuracy in a world that changes.

Case Study 3: The London Underground Map and the Meaning of “Accuracy”

The London Tube Map, introduced by Harry Beck in 1933, revolutionized the concept of cartographic truth. Beck realized that subway riders did not need geographic precision. They needed simplicity, clarity, and relational accuracy—knowing how stations connected, not how far apart they were in miles.

By replacing geographic realism with abstract geometry, he created a map that was technically inaccurate but functionally brilliant. Nearly all subway maps worldwide now follow the same principle. This case study illustrates that the “right” map is the map that serves the user’s need, not the map that most faithfully represents ground truth.

Case Study 4: Google Maps and the Algorithmic Cartographer

Google Maps represents an entirely new form of mapping. Unlike paper maps, it is not a static depiction of geography. It is a constantly shifting model created from satellite images, aerial photos, street-level observations, user reports, and complex routing algorithms. It recalculates itself continuously, adjusting for traffic, construction, business changes, and political variations in border representation.

Its power is extraordinary, but its limitations remind us that automation cannot eliminate human judgment. The platform reflects commercial incentives, political boundaries, and the imperfections of crowdsourced information. Accuracy is high but uneven, and like the ocean charts, the system must be updated constantly to remain trustworthy.

VI. A Unified Theory of Mapmaking

Across all eras and technologies, the mapmaker’s challenge remains the same. The world is too large and too complex to be perceived directly, so the mapmaker must choose which aspects of reality to capture. Those choices—shaped by purpose, tools, knowledge, and bias—determine whether the resulting map will be useful or misleading. Measurement introduces error; projection introduces distortion; interpretation introduces judgment. Accuracy is always relative to context, intention, and method.

The mapmaker succeeds not by eliminating error altogether, but by understanding its sources, managing its influence, and balancing the competing truths that every map must negotiate.

VII. Technical Appendices

Appendix A: Coordinate Systems and Projections

Modern mapping rests on systems that allow the entire Earth to be described mathematically. Latitude and longitude divide the globe into degrees, providing a universal reference easy to conceptualize but difficult to measure perfectly at large scales. The Universal Transverse Mercator (UTM) system divides the Earth into narrow vertical zones, each of which minimizes distortion for engineering purposes. The North American Datum (NAD83) and the World Geodetic System (WGS84) provide precise mathematical models of the Earth’s shape, enabling GPS receivers to calculate location with remarkable accuracy.

Map projections translate the curved surface of the Earth to a flat plane. Each projection sacrifices something: the Mercator preserves direction but exaggerates the size of high-latitude regions; equal-area projections maintain proportional land area at the cost of distorting continents; the Robinson projection compromises carefully to create a visually balanced world. The choice of projection reflects the map’s purpose more than the mapmaker’s preference.

Appendix B: Surveying Instruments Through Time

The tools of mapping have evolved dramatically. Ancient civilizations used gnomons to measure shadows, ropes to mark distances, and rudimentary cross-staffs to gauge angles. Renaissance innovations introduced compasses, astrolabes, sextants, and the plane table, bringing scientific precision to exploration. By the eighteenth century, the theodolite allowed surveyors to measure angles with unprecedented accuracy.

Modern surveyors rely on total stations, which combine angle measurement with laser-based distance calculation; GNSS receivers capable of centimeter-level precision; LiDAR instruments that generate three-dimensional point clouds of terrain; and drones that capture aerial photographs suitable for photogrammetric reconstruction. Although the instruments have changed, the underlying goal has remained constant: to measure the Earth in a way that minimizes error and maximizes reliability.

Appendix C: Sources of Error and How Mapmakers Correct Them

Cartographic errors emerge from several sources. Positional error occurs when instrument readings or GPS signals are distorted by environmental conditions, equipment limitations, or signal reflections from buildings or terrain. Projection error arises because any flat map must distort some combination of shape, area, direction, or distance. Human interpretation error appears during the classification of aerial images or the delineation of ambiguous features. Temporal error affects maps that have not been updated to reflect natural or man-made changes.

Mapmakers mitigate these errors by using redundant measurements, cross-checking data from multiple sources, incorporating ground-truth verification, applying statistical corrections, and selecting projections tailored to the region being mapped. Accuracy is achieved not through perfection but through a disciplined process of detecting, bounding, and correcting inevitable imperfections.

Conclusion: The Eternal Mind Behind the Map

From a Babylonian surveyor tying knots in a rope, to a Polynesian navigator reading waves in the dark, to Lewis and Clark marking compass bearings along unknown rivers, to a modern GIS analyst adjusting satellite layers on a computer screen, the mapmaker’s mind has never changed in its essential character. The world is too vast, varied, and dynamic to be seen directly, so we create representations—models that reveal structure, meaning, and relationship.

A map is not merely a depiction of space. It is a human judgment about what matters. Every accurate map represents a triumph of curiosity over ignorance, order over chaos, and understanding over confusion. The tools are part of the story, but the deeper story is the capability of the person wielding them: the patience to measure carefully, the discipline to verify and correct, the imagination to translate complexity into clarity, and the humility to know that no map is final, complete, or perfect.

Mapmaking is the oldest form of reasoning about the world, and perhaps the most enduring. To draw a map is to make the world legible. To understand a map is to understand the choices of the person who created it. And to appreciate accuracy is to recognize that behind every line lies a mind trying to grasp the infinite.