A collaboration between Lewis McLain and AI

Executive Summary

Municipal drone programs have rapidly evolved from experimental projects to dependable service tools. Today, Texas cities are beginning to treat drones not as gadgets but as core municipal utilities—shared resources as essential as fleet management, radios, or GIS. Properly implemented, drones can provide faster response times, safer job conditions, and higher-quality data, all while saving taxpayer money.

This paper explains how cities can build and sustain a municipal drone program. It examines current and emerging use cases, outlines staffing impacts, surveys training options and costs in Texas, explores fleet models and procurement, and considers the legal, policy, and community dimensions that must be addressed. It concludes with recommendations, case studies of failures, and appendices on payload regulation and FAA sample exam questions.

Handled wisely, drones will make cities safer, smarter, and more responsive. Mishandled, they risk creating public backlash, wasting funds, or even eroding trust.

The Case for Treating Drones as a Utility

Cities that succeed with drones do so by thinking of them as utilities, not toys. A drone program should be centrally governed, jointly funded, and transparently managed. Just like a municipal fleet or IT department, a citywide drone service must be reliable, equitable across departments, compliant with law, interoperable with other systems, and transparent to the public.

This approach ensures that drones are available where needed, that policies are consistent across departments, and that costs are shared fairly. Most importantly, it signals to residents that the city treats drone use seriously, with strong safeguards and clear accountability.

Current and Growing Uses

Across Texas and the country, municipal drones already serve a wide range of functions.

Public Safety: Police and fire agencies use drones as “first responders,” launching them from stations or rooftops to 911 calls. They provide live video of car crashes, fires, or hazardous scenes, often arriving before officers. Firefighters use drones with thermal cameras to locate victims or track hotspots in burning buildings.

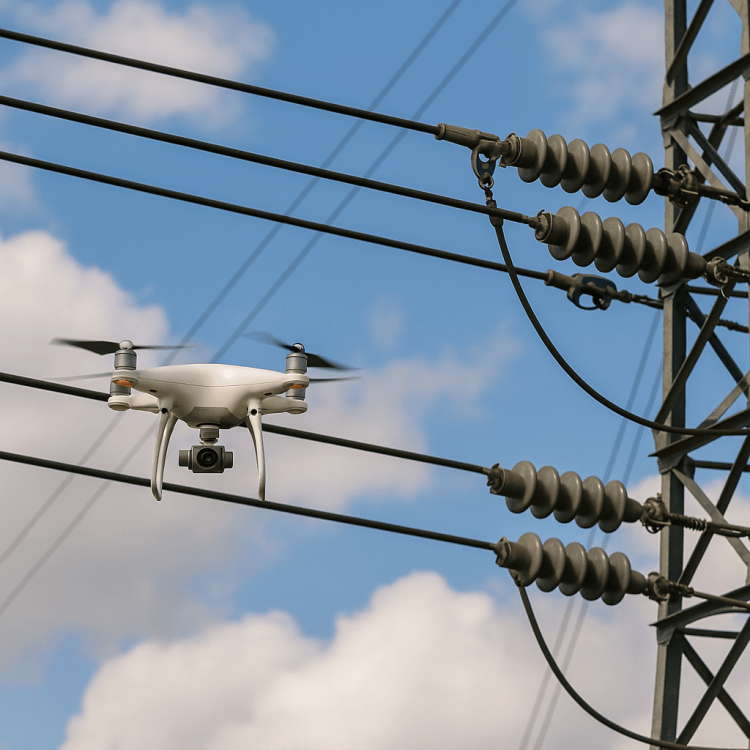

Infrastructure and Public Works: Drones inspect bridges, culverts, roofs, and water towers. Instead of sending workers onto scaffolds or into confined spaces, crews now fly drones that capture detailed photos and 3D models. Landfills are surveyed from the air, methane leaks identified, and storm damage mapped quickly after major events.

Transportation and Planning: Drones monitor traffic flow, study queue lengths, and document work zones. City planners use them to create up-to-date maps, support zoning decisions, and maintain digital twins of urban areas.

Environmental and Health: From checking stormwater outfalls to mapping tree canopies, drones help environmental staff monitor city assets. In some regions, drones are used to identify standing water and apply larvicides for mosquito control.

Emergency Management: After floods, hurricanes, or tornadoes, drones provide rapid situational awareness, helping cities prioritize response and document damage for FEMA claims.

As automation improves, “drone-in-a-box” systems—drones that launch on schedule or in response to sensors—will soon become common municipal tools.

Staffing Impacts

A common fear is that drones will replace jobs. In practice, they save lives and money while creating new roles.

Jobs Saved: By reducing risky tasks like climbing scaffolds or entering confined spaces, drones make existing jobs safer. They also reduce overtime by finishing inspections or surveys in hours instead of days.

Jobs Added: Cities now employ drone program coordinators, FAA Part 107-certified pilots, data analysts, and compliance officers. A medium-sized Texas city might add ten to twenty such roles over the next five years.

Jobs Shifted: Inspectors, police officers, and firefighters increasingly become “drone-enabled” workers, adding aerial operations to their responsibilities. Over time, 5–10% of municipal staff in critical departments may be retrained in drone use.

The net result is redistribution rather than reduction. Drones are not eliminating jobs; they are elevating them.

Training in Texas

FAA rules require every commercial or government drone operator to hold a Part 107 Remote Pilot Certificate. Fortunately, Texas offers many affordable training options.

Community colleges such as Midland College and South Plains College provide Part 107 prep and hands-on flight training, typically costing $350 to $450 per course. Private providers like Dronegenuity and From Above Droneworks offer in-person and hybrid courses ranging from $99 online modules to $1,200 full academies. San Jacinto College and other universities run short workshops and certification tracks.

Online exam prep courses are widely available for $150–$400, making it feasible to train multiple staff at once. When departments train together, cities often negotiate group discounts and host joint scenario days at municipal training grounds.

Fleet Models and Costs

Municipal needs vary, but most cities benefit from a tiered fleet.

- Micro drones (under 250g) for training and quick checks: $500–$1,200.

- Utility quads for mapping and inspection: $2,500–$6,500.

- Enterprise drones with thermal sensors for public safety: $7,500–$16,000.

- Heavy-lift or VTOL systems for long corridors or specialized sensors: $18,000–$45,000+.

Each drone has a three- to five-year lifespan, with batteries refreshed every 200–300 cycles. Cities must also budget for accessories, insurance, and management software.

Policy and Legal Landscape

Federally, the FAA regulates drone operations under Part 107. Rules limit altitude to 400 feet, require flights within visual line of sight, and mandate Remote ID for most aircraft. Waivers can allow for advanced operations, such as flying beyond visual line of sight (BVLOS).

In Texas, additional laws restrict image capture in certain contexts and impose rules around critical infrastructure. Local governments cannot regulate airspace, but they can and should regulate employee conduct, data use, privacy, and procurement.

Transparency is crucial. Cities must publish clear retention policies, flight logs, and citizen FAQs.

Privacy, Labor, and Community Trust

For communities to embrace drones, cities must be proactive.

Privacy: Drones should collect only what is necessary, with cameras pointed at mission targets rather than private backyards. Non-evidentiary footage should be deleted within 30–90 days.

Labor: Cities should emphasize that drones augment rather than replace workers. They shift dangerous tasks to machines while providing staff new certifications and career paths.

Equity: Larger cities may advance faster than small towns, but shared services, inter-local agreements, and regional training programs can close the gap.

Community Trust: Transparency builds legitimacy. Cities should publish quarterly metrics, log complaints, host public demos, and maintain a clear point of contact for concerns.

Lessons from Failures

Not every program has succeeded. Across the country, drone initiatives have stumbled in predictable ways:

- Community Pushback: Chula Vista’s pioneering drone-as-first-responder program drew criticism for surveillance concerns, while New York City’s holiday monitoring drones sparked public backlash. Lesson: transparency and engagement must come first.

- Operational Incidents: A Charlotte police drone crashed into a house, and some agencies lost FAA waivers due to compliance lapses. Lesson: one mistake can jeopardize an entire program; training and discipline are essential.

- Budget Failures: Dallas and other cities saw expansions stall over hidden costs for software and maintenance. Smaller towns wasted funds buying consumer drones that quickly wore out. Lesson: plan for lifecycle costs, not just hardware.

- Legal Overreach: Connecticut’s proposal to arm police drones with “less-lethal” weapons collapsed amid backlash, while San Diego faced court challenges over warrant requirements. Lesson: pushing boundaries invites restrictions.

- Scaling Gaps: Rural Texas counties bought drones with grants but lacked certified pilots or insurance. Small towns gathered imagery but had no analysts to use it. Lesson: drones without people and integration are wasted purchases.

Recommendations

- Invest in training through Texas colleges and private providers.

- Procure wisely, choosing modular, upgradeable hardware.

- Adopt clear policies on payloads, privacy, and data retention.

- Prioritize non-kinetic payloads such as cameras, sensors, and lighting.

- Prepare for BVLOS, which will transform municipal use once authorized.

- Ensure equity, supporting smaller cities through regional cooperation.

Conclusion

Drones are no longer experimental novelties. They are rapidly becoming a core municipal utility—a shared service as essential as public works fleets or GIS. Their greatest promise lies not in flashy technology but in the steady, practical benefits they bring: safer workers, faster response, better data, and more transparent government.

But the promise depends on choices. Cities must prohibit weaponized payloads, publish clear policies, train and retrain staff, and engage openly with their communities. Done right, drones can strengthen both city effectiveness and public trust.

Appendix A: Administrative Regulation on Payloads

Title: Drone Payloads and Weapons Prohibition; Data & Safety Controls

Number: AR-UAS-01

Effective Date: Upon issuance

Applies To: All city employees, contractors, volunteers, or agents operating drones (UAS) on behalf of the City

1. Purpose

This regulation ensures that all municipal drone operations are conducted lawfully, ethically, and safely. It establishes clear prohibitions on weaponized or harmful payloads and sets minimum standards for data use, transparency, and accountability.

2. Definitions

- UAS (Drone): An uncrewed aircraft and associated equipment used for flight.

- Payload: Any item attached to or carried by a UAS, including cameras, sensors, lights, speakers, or drop mechanisms.

- Weaponized or Prohibited Payload: Any device or substance intended to incapacitate, injure, damage, or deliver kinetic, chemical, electrical, or incendiary effects.

- Authorized Payload: Sensors or devices explicitly approved by the UAS Program Manager for municipal purposes.

3. Policy Statement

- The City strictly prohibits the use of weaponized or prohibited payloads on all drones.

- Drones may only be used for documented municipal purposes, consistent with law, FAA rules, and City policy.

- All payloads must be inventoried and approved by the UAS Program Manager.

4. Prohibited Payloads

The following are expressly prohibited:

- Firearms, ammunition, or explosive devices.

- Pyrotechnic, incendiary, or chemical agents (including tear gas, pepper spray, smoke bombs).

- Conducted electrical weapons (e.g., TASER-type devices).

- Projectiles, hard object drop devices, or kinetic impact payloads intended for crowd control.

- Covert audio or visual recording devices in violation of state or federal law.

Exception: Non-weaponized lifesaving payloads (e.g., flotation devices, first aid kits, rescue lines) may be deployed only with prior written approval of the Program Manager and after a documented risk assessment.

5. Authorized Payloads

Authorized payloads include, but are not limited to:

- Imaging sensors (visual, thermal, multispectral, LiDAR).

- Environmental sensors (methane detectors, gas analyzers, air quality monitors).

- Lighting systems (searchlights, strobes).

- Loudspeakers for announcements or evacuation instructions.

- Non-weaponized emergency supply drops (medical kits, flotation devices).

- Tethered systems for persistent observation or communications relay.

6. Oversight and Accountability

- The UAS Program Manager must approve all payload configurations before deployment.

- Departments must maintain an updated inventory of drones and payloads.

- Quarterly inspections will be conducted to verify compliance.

- An annual public report will summarize drone use, payload types, and incidents.

7. Data Controls

- Minimization: Only record what is necessary for the mission.

- Retention:

- Non-evidentiary footage: 30–90 days.

- Evidentiary footage: retained per case law.

- Mapping/orthomosaics: retained per project records schedule.

- Access: Role-based permissions, with audit logs.

- Public Release: Media released under public records law must be reviewed for privacy and redaction (faces, license plates, sensitive sites).

8. Training Requirements

- All operators must hold an FAA Part 107 Remote Pilot Certificate.

- Annual city-approved training on:

- This regulation (AR-UAS-01).

- Privacy and data retention.

- Citizen engagement and de-escalation.

- Scenario-based training must be conducted at least once per year.

9. Enforcement

- Violations of this regulation may result in disciplinary action up to and including termination of employment or contract.

- Prohibited payloads will be confiscated, logged, and removed from service.

- Cases involving unlawful weaponization will be referred for criminal investigation.

10. Effective Date

This regulation is effective immediately upon approval by the City Manager and shall remain in force until amended or rescinded.

Appendix B: FAA Part 107 Sample Questions (Representative, 25 Items)

Note: These questions are drawn from FAA study materials and training resources. They are not live exam questions but are representative of the knowledge areas tested.

- Under Part 107, what is the maximum allowable altitude for a small UAS?

A. 200 feet AGL

B. 400 feet AGL ✅

C. 500 feet AGL - What is the maximum ground speed allowed?

A. 87 knots (100 mph) ✅

B. 100 knots (115 mph)

C. 87 mph - To operate a small UAS for commercial purposes, which certification is required?

A. Private Pilot Certificate

B. Remote Pilot Certificate with a small UAS rating ✅

C. Student Pilot Certificate - Which airspace requires ATC authorization for UAS operations?

A. Class G

B. Class C ✅

C. Class E below 400 ft - How is controlled airspace authorization obtained?

A. Verbal ATC request

B. Filing a VFR flight plan

C. Through LAANC or DroneZone ✅ - Minimum visibility requirement for Part 107 operations?

A. 1 statute mile

B. 3 statute miles ✅

C. 5 statute miles - Required distance from clouds?

A. 500 feet below, 2,000 feet horizontally ✅

B. 1,000 feet below, 1,000 feet horizontally

C. No minimum distance - A METAR states: KDAL 151853Z 14004KT 10SM FEW040 30/22 A2992. What is the ceiling?

A. Clear skies

B. 4,000 feet few clouds ✅

C. 4,000 feet broken clouds - A TAF includes BKN020. What does this mean?

A. Broken clouds at 200 feet

B. Broken clouds at 2,000 feet ✅

C. Overcast at 20,000 feet - High humidity combined with high temperature generally results in:

A. Increased performance

B. Reduced performance ✅

C. No effect - If a drone’s center of gravity is too far aft, what happens?

A. Faster than normal flight

B. Instability, difficult recovery ✅

C. Less battery use - High density altitude (hot, high, humid) causes:

A. Increased battery life

B. Decreased propeller efficiency, shorter flights ✅

C. No effect - A drone at max gross weight of 55 lbs carries a 10 lb payload. Payload percent?

A. 18% ✅

B. 10%

C. 20% - At maximum gross weight, performance is:

A. Improved stability

B. Reduced maneuverability and endurance ✅

C. No change - The purpose of Crew Resource Management is:

A. To reduce paperwork

B. To use teamwork and communication to improve safety ✅

C. To reduce training costs - GPS signal lost and drone drifts — first action?

A. Immediate Return-to-Home

B. Switch to ATTI/manual mode, maintain control, land ✅

C. Climb higher for GPS - If a drone causes $500+ in property damage, what is required?

A. Report only to local police

B. FAA report within 10 days ✅

C. No report required - If the remote PIC is incapacitated, the visual observer should:

A. Land the drone ✅

B. Call ATC

C. Wait until PIC recovers - On a sectional chart, a magenta vignette indicates:

A. Class E starting at surface ✅

B. Class C boundary

C. Restricted airspace - A dashed blue line on a sectional chart indicates:

A. Class B airspace

B. Class D airspace ✅

C. Class G airspace - A magenta dashed circle indicates:

A. Class E starting at surface ✅

B. Class G airspace

C. No restrictions - Floor of Class E when sectional shows fuzzy side of a blue vignette?

A. Surface

B. 700 feet AGL ✅

C. 1,200 feet AGL - Main concern with fatigue while flying?

A. Reduced battery performance

B. Slower reaction and poor decision-making ✅

C. Increased radio interference - Alcohol is prohibited within how many hours of UAS operation?

A. 4 hours

B. 8 hours ✅

C. 12 hours - Maximum allowable BAC for remote pilots?

A. 0.08%

B. 0.04% ✅

C. 0.02%