The Day the iPhone Rewired the World

A collaboration between Lewis McLain & AI

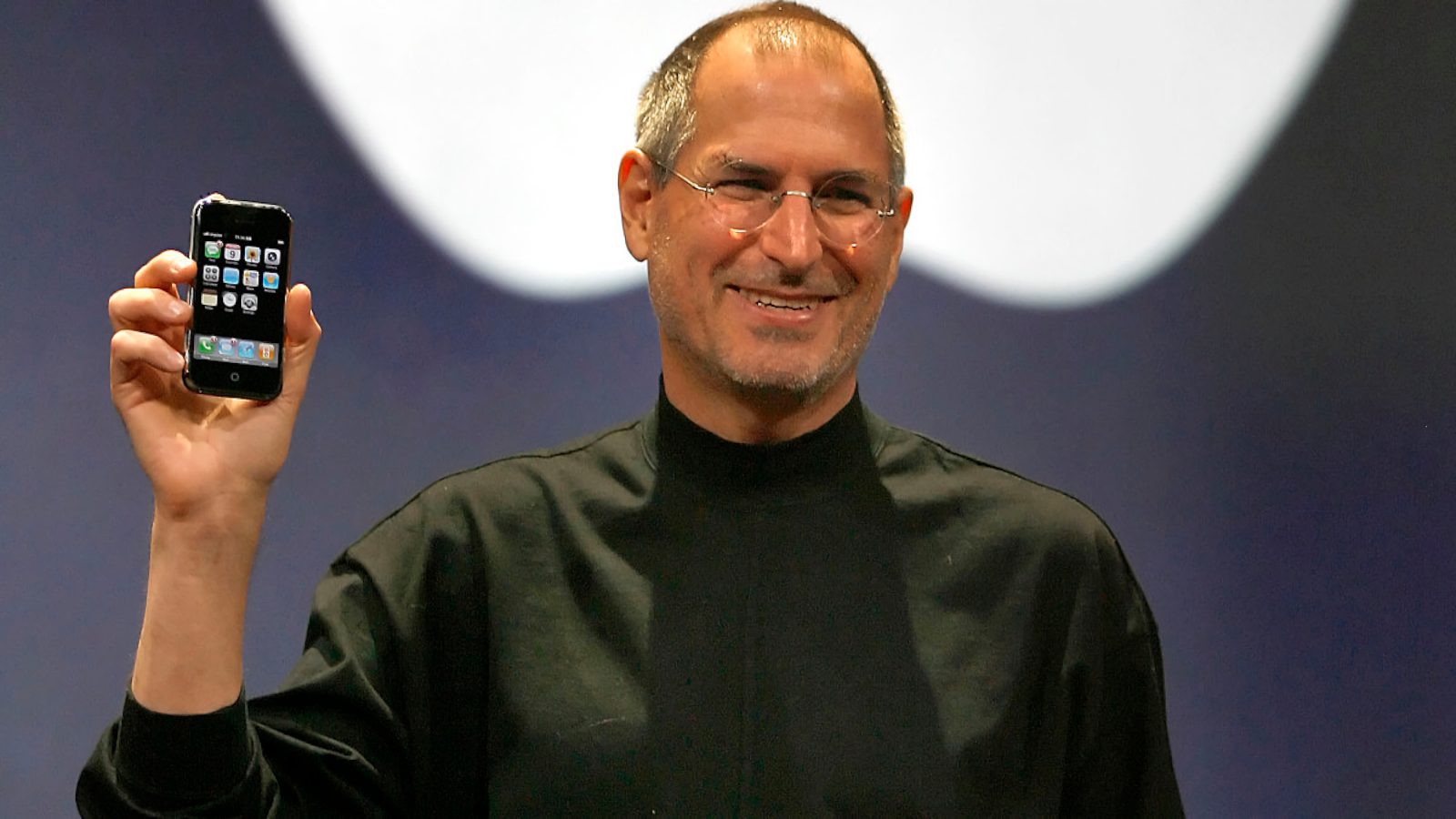

On January 9, 2007, at Macworld in San Francisco, Steve Jobs walked onto the stage and delivered one of the most consequential product announcements in modern history. He framed it theatrically—three devices in one: an iPod, a phone, and an internet communicator. Then he paused, smiled, and revealed the trick. They were not three devices. They were one. The Apple iPhone had arrived.

What followed was not merely a successful product launch. It was a hinge moment—one that quietly reordered how humans interact with technology, with information, with each other, and even with themselves.

What Made the iPhone Event Different

The iPhone announcement mattered not because it was the first smartphone, but because it redefined what a phone was supposed to be.

At the time, the market was dominated by devices with physical keyboards, styluses, nested menus, and clunky mobile browsers. BlackBerry owned business communication. Nokia owned scale. Microsoft owned enterprise software assumptions. Apple owned none of these markets.

Yet the iPhone introduced several radical departures:

- Multi-touch as the interface

Fingers replaced keyboards and styluses. Pinch, swipe, and tap turned abstract computing into something instinctive and physical. - A real web browser

Not a stripped-down “mobile” version of the internet, but the actual web—zoomable, readable, usable. - Software-first design

The device wasn’t defined by buttons or ports but by software, animations, and user experience. Hardware existed to serve software, not the other way around. - A unified ecosystem vision

The iPhone was conceived not as a gadget but as a node—connected to iTunes, Macs, carriers, and eventually an App Store that did not yet exist but was already implied.

Jobs did not spend the keynote talking about specs. He talked about experience. That choice alone signaled a philosophical shift in consumer technology.

The Immediate Shockwave

The reaction was mixed. Some praised the elegance. Others mocked the lack of a physical keyboard, the high price, and the absence of third-party apps at launch. Industry leaders dismissed it as a niche luxury device.

Those critiques aged poorly.

Within a few years, nearly every phone manufacturer had abandoned keyboards. Touchscreens became universal. Mobile operating systems replaced desktop metaphors. The skeptics were not foolish—they were anchored to the past in a moment when the ground moved.

How the iPhone Changed Everyday Life

The iPhone did not just change phones. It collapsed entire categories of human activity into a pocket-sized slab of glass.

Communication shifted from voice-first to text, image, and video-first. Navigation moved from paper maps and memory to GPS-by-default. Photography became constant and social rather than occasional and deliberate. The internet ceased to be a place you “went” and became something you carried.

Several deeper changes followed:

- Time became fragmented

Micro-moments—checking, scrolling, responding—filled the spaces once occupied by waiting, boredom, or reflection. - Attention became a resource

Notifications, feeds, and apps competed continuously for awareness, reshaping media, advertising, and even politics. - Work escaped the office

Email, documents, approvals, and meetings followed people everywhere, blurring boundaries between professional and personal life. - Memory outsourced itself

Phone numbers, directions, appointments, even photographs replaced recall with retrieval.

The iPhone did not force these changes, but it made them frictionless, and friction is often the last defense of human habits.

The App Store Effect

A year later, Apple launched the App Store, and the iPhone’s impact accelerated exponentially. Developers gained a global distribution platform overnight. Entire industries emerged—ride-sharing, mobile banking, food delivery, social media influencers, mobile gaming—built on the assumption that everyone carried a powerful computer at all times.

This was not just technological leverage. It was economic leverage.

Apple positioned itself as the gatekeeper of a new digital economy, collecting a share of transactions while letting others shoulder innovation risk. Few business models in history have been so scalable with so little marginal cost.

The Financial Transformation of Apple

Before the iPhone, Apple was a successful but niche computer company. After the iPhone, it became something else entirely.

The iPhone evolved into Apple’s single largest revenue driver, often accounting for roughly half of annual revenue in its peak years. More importantly, it pulled customers into a broader ecosystem—Macs, iPads, Apple Watch, AirPods, services, subscriptions—each reinforcing the others.

Apple’s profits followed accordingly:

- Revenue grew from tens of billions annually to hundreds of billions

- Gross margins remained unusually high for a hardware company

- Cash reserves swelled to levels rivaling national treasuries

- Apple became, at times, the most valuable company in the world

The genius was not just the device. It was the integration—hardware, software, services, and brand operating as a single system. Competitors could copy features, but not the whole machine.

The Long View

January 9, 2007, now looks less like a product launch and more like a civilizational inflection point. The iPhone compressed computing into daily life so completely that it is now difficult to remember what came before.

That power has brought wonder and convenience—and distraction, dependency, and new ethical dilemmas. Tools that shape attention inevitably shape culture.

Apple did not merely sell a phone that day. It sold a future—one we are still living inside, still arguing about, and still trying to understand.