Miss Saigon: Love, Illusion, and the Mirage of the American Dream

A collaboration between Lewis McLain & AI

“You are sunlight and I moon, joined by the gods of fortune.”

— “Sun and Moon”

This dramatic musical was so remarkable to me. I remember writing that it was the best I had ever witnessed at the time, and wondering if I would ever see a better play. I think I saw it three times. The first time was in NYC, and the other two times were in Dallas. They were different in a few ways. The Dallas version was even more profound in the way they handled the opening of the second act. I will never forget the players and emotional content. LFM

I. The World in Ruin, the Heart Still Beating

In Miss Saigon, the world is ending in slow motion. Helicopters thunder above the city, neon signs flicker over shattered streets, and the air hums with the machinery of empire. Yet in the ruins of Saigon, two hearts still find each other. Kim and Chris meet not in peace but in aftermath—he, a disoriented soldier of a collapsing foreign power; she, a displaced orphan forced into a bar called Dreamland. Around them, history howls. Within them, something eternal stirs.

Their love begins as an accident of war but unfolds like a parable of Eden after the Fall: purity glimpsed in a poisoned world. “You are sunlight and I moon,” Kim sings, echoing Genesis more than Puccini—light and darkness yearning toward wholeness, even as they know their union is impossible. The tragedy of Miss Saigon is not simply that love fails; it is that love, though true, cannot redeem the systems that contain it.

II. The Gospel According to Kim

Kim is among the most spiritually resonant heroines of modern theater—a Christ-figure clothed in the garments of an Asian peasant girl. Her purity is not naivety but faith: a conviction that love can sanctify even the most defiled landscape. When Chris leaves her amid the chaos of Saigon’s fall, Kim does not curse him or her fate. She gathers their son, Tam, and holds him as both burden and promise. “You will see me through another season,” she seems to tell God, echoing Mary sheltering the child Messiah in exile.

Years later, in Bangkok, when confronted by Chris’s American wife, Kim’s theology of love reaches its consummation. She chooses death not as surrender but as offering: “Now you must take Tam with you / And you must go on / I’m dying for your sake, my son.” In that moment, Miss Saigon transcends its setting. Kim becomes every mother who has loved into suffering, every believer who has poured out life for another’s salvation. Her sacrifice restores no empire and reforms no politics—but it restores meaning.

To love purely, the musical insists, is to suffer. Yet in that suffering lies a kind of resurrection. When Chris cries over her body—“How in one night have we come so far?”—we hear the echo of humanity’s ancient lament: love arrives divine and departs crucified.

III. The Engineer and the False Heaven

“The American Dream / Is gonna make my dream come true.”

If Kim represents the soul’s yearning for redemption, the Engineer embodies civilization’s addiction to illusion. He is the show’s dark chorus—half clown, half devil, half prophet—hawking the fantasy of America as the new Jerusalem of lust and consumption. His anthem, “The American Dream,” drips with irony: “They’ll have a club for all the rich to join / Where you can drive your Cadillac through the eye of a needle.” It is a parody of Scripture, a theology of greed replacing the Beatitudes with billboards.

The Engineer’s dream is the shadow twin of Kim’s faith. Both are migrants of hope; both seek deliverance. But where Kim’s vision demands self-sacrifice, the Engineer’s demands self-erasure. His dream is not of freedom but of becoming the very machine that once enslaved him. He worships America not as idea but as idol—its neon signs as stained glass, its dollar bills as sacraments. Through him, the musical indicts a modern form of empire: not territorial but spiritual, not conquest but consumption.

In the end, the Engineer does make it to America, but his triumph is hollow. He ascends the staircase of Ellis Island as if entering heaven, yet we hear no music of redemption—only brass and discord. The promised paradise is another illusion; the dream devours its dreamer.

IV. The Mirage of Salvation

The love between Kim and Chris is real; the salvation offered by nations and ideologies is not. That is the paradox at the heart of Miss Saigon. When Chris returns to find Kim years later, married and broken by guilt, his words in “The Confrontation”—“You’re here—Oh my God, you’re here!”—carry the force of resurrection. But it is too late. The world they inhabited has no place for resurrections. Kim’s suicide is not despair but testimony: that no earthly dream can absorb the fullness of love. Her body falls between two worlds—Asia and America, heaven and earth—and her blood exposes the lie that either side could claim moral victory.

Boublil and Schönberg thus turn history into allegory. The fall of Saigon becomes the Fall itself: humankind’s expulsion from innocence, still chasing salvation in the mirage of progress. The helicopter that lifts the last Americans away becomes a steel angel guarding the gate of paradise—an emblem of the separation between what is real and what we wish were real.

V. The Music of Heaven and the Sound of Machines

The score of Miss Saigon is not mere accompaniment; it is theology in melody. The lush orchestration, the merging of Asian tonal motifs with Western harmonies, enacts the same cultural collision as the story itself. In “I Still Believe,” Kim and Ellen sing the same words across oceans: “I still believe you will return / I know you will.” Two women, one melody, one delusion—the human capacity to believe even against evidence. This duet is not about romantic hope but about the nature of faith: to believe is to risk being wrong, and to love is to be wounded by that risk.

Likewise, “Bui Doi” (“dust of life”) transforms what could be sentimental into prophetic lament:

“They are the living reminder of all the good we failed to do.”

It is confession as chorus—the entire nation singing its mea culpa. The orphans of Saigon become symbols of moral residue, the souls left behind by history’s machinery. The music soars, not to glorify but to accuse.

VI. “Bui Doi” — The Children of Dust and the Conscience of a Nation

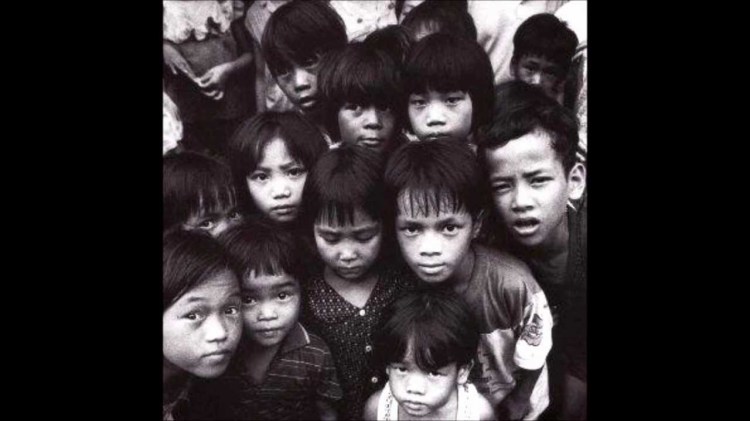

At the opening of the second act, the curtain rises not on Saigon or Bangkok, but on America’s memory—a stage transformed into a tribunal of conscience.

A single voice, John’s, steps forward beneath the glow of a projected photograph. His song, “Bui Doi,” erupts like thunder through the theater: a requiem, a sermon, and a national confession.

They’re called Bui-Doi.

The dust of life.

Conceived in Hell,

And born in strife.

They are the living reminder of all the good we failed to do.

We can’t forget

Must not forget

That they are all our children, too.Like all survivors I once thought

When I’m home I won’t give a damn

But now I know I’m caught, I’ll never leave VietnamWar isn?t over when it ends, some pictures never leave youmind.

They are the faces of the children the ones we left behind

They?re called Bui-doi.

The dust of life, conceived in hell and born in strife

They are the living reminders of all the good we failed to do

That?s why we know deep in our hearts, that they are all ourchildren tooThese kids hit walls on ev?ry side, they don?t belong in anyplace.

Their secret they can?t hide it?s printed on their face.

I never thought one day I?d plead

For half-breeds from a land that?s torn

But then I saw a camp for children whose crime was being bornThey’re called Bui-Doi, the dust of life conceived in hell and born in strife.

We owe them fathers and a family a loving home they never knew.

Because we know deep in our hearts that they are all our children too.These are souls in need, they need us to give

Someone has to pay for their chance to live

Help me tryThey’re called Bui-Doi.

The dust of life.

Conceived in Hell,

And born in strife.

They are the living reminders of all the good we failed to do.

That’s why we know

That’s why we know

Deep in our hearts

Deep in our hearts

That’s why we know

That they are all our children, too.

The Vietnamese phrase Bui Doi means “dust of life.” It names the children born of the war—half American, half Vietnamese—unclaimed by either world. But the phrase carries more than pity; it carries theology. In Genesis, humanity itself is formed from dust. To call these children “dust” is to recall creation and abandonment in a single breath. They are the living proof of divine image forgotten—the breath of life exhaled and left to drift.

John, once the soldier’s companion, now stands as the prophet. His voice shakes with the weight of unrepented sin:

“They are the living reminder of all the good we failed to do.”

That line cuts deeper than any artillery blast. It indicts not merely a nation but a civilization addicted to amnesia. The men’s chorus behind him—uniformed, disciplined, proud—becomes the choir of a guilty church. The horns sound like the trumpets of judgment; the snare rolls like the echo of marching ghosts. This is liturgy as lament, where patriotism and repentance collide.

Musically, the song is both anthem and elegy. The brass proclaims victory; the strings mourn the cost. The melody rises toward triumph but collapses into minor chords—hope bleeding into remorse. Boublil and Schönberg understood that guilt itself has rhythm, that moral awakening can be scored.

Philosophically, “Bui Doi” reframes the entire musical. It transforms Miss Saigon from personal tragedy to collective confession. Kim’s sacrifice in Act I was individual; this is national. Her love sanctified one child; this song pleads for all of them. In that sense, “Bui Doi” functions as the Mass of the piece—the moment when the audience, too, becomes congregation, murmuring its mea culpa in the dark.

VII. The Cinematic Mirror

In most major productions, “Bui Doi” is not sung to an empty backdrop but accompanied by film and photographs—documentary images of the real aftermath of war. As John sings, the theater dissolves into a moving archive: Vietnamese children of mixed heritage, refugee camps, faces pressed against wire and window.

This cinematic layer breaks the fourth wall. It shatters illusion and turns the audience into witness. The theater becomes a courtroom of conscience, the spectators no longer observers but participants in the confession.

It is one of the most striking multimedia sequences in stage history—fiction colliding with fact, melody colliding with memory. The children on screen do not sing, but their images form the silent choir beneath the orchestra’s thunder. When the camera pans across those faces and John intones,

“They are the living reminder of all the good we failed to do…”

the entire house falls still. The song becomes cinema, the cinema becomes prayer.

For a few minutes, Miss Saigon ceases to be a musical and becomes a moral documentary in song—a thunderous meditation on guilt, compassion, and the possibility of redemption through remembrance.

VIII. The Theological Horizon

Philosophically, Miss Saigon rests on one question:

Can love redeem a world built on illusion?

The answer is both yes and no. Kim’s love redeems her soul but cannot redeem the system. The Engineer’s illusion sustains his survival but damns his humanity. America itself becomes a metaphor for mankind’s restless migration toward false heavens—a new Babylon promising light but delivering neon.

In biblical terms, the musical is a modern Ecclesiastes. Everything is vanity: war, politics, even dreams. Yet amid that vanity, a single act of selfless love pierces the darkness. When Kim sings “The Sacred Bird” to Tam, she becomes both Mary and Magdalene—mourning and believing, broken yet beautiful.

Her death is not defeat but transcendence: she forces Chris to confront the cost of love, and through him, the audience to confront its own moral anesthesia. The play ends with Chris kneeling, unable to resurrect her, and the music fading into silence. That silence is judgment—the sound of conscience awakening.

IX. Conclusion: The Love That Outlives Empires

“And if you can forgive me now / For all the things I’ve done / Then I will be the one who’ll stay.”

Empires fall, dreams fade, illusions shatter—but love remains, not as sentiment but as wound.

Miss Saigon is not simply a retelling of Madame Butterfly; it is a spiritual reckoning. It asks whether humanity, in its hunger for progress, has forgotten the sacred art of sacrifice.

Kim’s death redeems nothing external—no nation, no system—but it redeems the meaning of love itself.

In her final act, she transforms the stage of war into an altar. The Engineer’s dream dissolves in irony, but Kim’s faith survives in silence. She proves that even in the rubble of civilization, the human heart can still whisper its prayer to heaven:

“You are sunlight and I moon / Joined here, brightening the sky.”

And for a moment, however brief, the audience feels that sky brighten—proof that art, like love, can still make light out of ruin.

You must be logged in to post a comment.