A collaboration between Lewis McLain & AI

INTRODUCTION

The war in Ukraine is now in its fourth year. Ukraine has shown resilience and valor, yet the military, economic, and demographic realities are increasingly difficult. Russia has absorbed sanctions, mobilized industry, and stabilized its front lines. The United States and Europe continue to support Ukraine, but both face growing political and fiscal constraints.

Against this backdrop, U.S. national security officials drafted a 28-point peace framework (as reported by Reuters, The Washington Post, ABC News, and The Guardian). The document appears to have been an exploratory starting point—one that tested which elements might be negotiable.

Ukraine, Europe, and many in Washington immediately objected to several provisions. As a result, a revised 19-point framework emerged, significantly amending or deleting many of the Russia-leaning elements.

Below is the complete, authoritative breakdown of the original 28-point plan and the revised 19-point plan, with all points explained, sourced, amended, and analyzed.

I. TERRITORIAL & POLITICAL POINTS

1. Freeze the front line as the ceasefire line

Original (as reported by Reuters on Nov. 24, 2025, citing two senior U.S. officials familiar with the draft):

The draft called for an immediate ceasefire, freezing forces along the current line of contact.

Explanation:

Freezing the line stops the fighting, but battlefield lines often solidify into political borders. Because Russia holds more territory, a freeze risks entrenching Russian gains unless non-recognition is spelled out clearly.

Amended:

Ceasefire line remains, but explicitly does not confer legal recognition of Russian control.

U.S. reaction:

Supportive — ceasefire without legitimization.

Russia reaction:

Likely negative — Moscow prefers implicit recognition.

Strategic impact:

Buys time without surrendering legal sovereignty.

2. Ukraine formally accepts Russian control over Luhansk

Original (as reported by The Washington Post on Nov. 24, 2025, citing European diplomats briefed on the text):

Ukraine would acknowledge Russian control over most of Luhansk.

Explanation:

This would have forced Ukraine to surrender constitutional territory and millions of citizens—politically impossible.

Amended:

Deleted entirely.

U.S. reaction:

Positive — avoids violating sovereignty norms.

Russia reaction:

Negative — Russia seeks international recognition of annexation.

Strategic impact:

Prevents loss of internationally recognized territory.

3. Ukraine formally accepts Russian control over Donetsk

Original (as reported by ABC News on Nov. 23, citing officials familiar with Geneva discussions):

The proposal included formal acceptance of Russia’s hold on most of Donetsk.

Explanation:

Legitimizing Russia’s Donbas claims would validate ten years of aggression and destabilize Ukraine’s government.

Amended:

Deleted entirely.

U.S. reaction:

Relieved.

Russia reaction:

Disappointed.

Strategic impact:

Keeps Donetsk’s status open for negotiation.

4. Ukraine acknowledges Russian control of Crimea

Original (as reported by Reuters on Nov. 24, citing U.S. officials):

Included language implying de facto recognition of Russia’s 2014 annexation.

Explanation:

Would set a global precedent for territorial seizure by force.

Amended:

All recognition language removed.

U.S. reaction:

Supportive — maintains non-recognition.

Russia reaction:

Very negative — Crimea is central to Putin’s narrative.

Strategic impact:

Preserves Crimea’s legal status as Ukrainian territory.

5. International referendums in occupied territories

Original (as reported by The Guardian on Nov. 24, citing diplomatic sources):

Proposed internationally monitored referendums on whether occupied areas would join Russia.

Explanation:

Impossible to conduct fairly under occupation; Russia controls the environment.

Amended:

Referendum mechanism eliminated.

U.S. reaction:

Supportive — avoids sham legitimacy.

Russia reaction:

Strongly negative — Russia relies on referendums.

Strategic impact:

Prevents artificially legitimizing annexed areas.

6. Demilitarized buffer zone

Original (as reported by Reuters on Nov. 24, citing U.S. security officials):

The draft proposed a demilitarized zone separating forces.

Explanation:

DMZs often require the weaker side (Ukraine) to withdraw further, giving the stronger one (Russia) strategic depth.

Amended:

Replaced with flexible “security arrangements.”

U.S. reaction:

Positive — avoids disadvantaging Ukraine.

Russia reaction:

Likely dissatisfied.

Strategic impact:

Keeps negotiations flexible and avoids a pre-engineered imbalance.

II. MILITARY & SECURITY POINTS

7. Ukraine permanently renounces NATO membership

Original (as reported by The Washington Post, Nov. 21, citing U.S. and EU officials):

The draft included a requirement that Ukraine adopt permanent neutrality and ban NATO membership.

Explanation:

This is Russia’s top strategic goal; it would permanently weaken Ukraine’s security.

Amended:

Deleted — NATO membership deferred, not denied.

U.S. reaction:

Strong support.

Russia reaction:

Highly negative.

Strategic impact:

Preserves Ukraine’s long-term security options.

8. Cap Ukraine’s armed forces at ~600,000

Original (as reported by ABC News on Nov. 23, citing negotiators):

The draft proposed a strict cap on Ukraine’s troop numbers.

Explanation:

A fixed cap locks Ukraine into inferiority while Russia remains unconstrained.

Amended:

Removed entirely.

U.S. reaction:

Positive.

Russia reaction:

Negative.

Strategic impact:

Prevents structural disadvantage.

9. Ban NATO bases in Ukraine

Original (as reported by Reuters, Nov. 24):

Included a blanket prohibition of foreign bases.

Explanation:

Would constrain Western military support.

Amended:

Softened to “no sudden deployments.”

U.S. reaction:

Acceptable.

Russia reaction:

Wanted a hard ban.

Strategic impact:

Allows future Western cooperation.

10. Limit NATO deployments in Eastern Europe

Original (as reported by The Guardian on Nov. 24):

Restricted NATO troop presence near Russia.

Explanation:

Gives Russia de facto influence over NATO decisions.

Amended:

Rewritten as non-binding “avoid escalatory moves.”

U.S. reaction:

Strong approval.

Russia reaction:

Unhappy.

Strategic impact:

Maintains NATO autonomy.

11. Intrusive inspections of Ukraine’s military

Original (as reported by ABC News, citing Geneva officials):

Allowed inspectors to verify Ukrainian compliance.

Explanation:

Resembles armistice terms for defeated states.

Amended:

Replaced with voluntary transparency.

U.S. reaction:

Approves.

Russia reaction:

Opposes — inspections favored Russia.

Strategic impact:

Protects Ukraine’s sovereignty.

12. U.S.-chaired Peace Council

Original (as reported by Reuters on Nov. 24, citing U.S. officials):

Placed the U.S. in charge of compliance oversight.

Explanation:

Alienates Europe; Russia distrusts unilateral U.S. leadership.

Amended:

Recast as a multinational body.

U.S. reaction:

Accepts.

Russia reaction:

Mixed.

Strategic impact:

Enhances legitimacy and reduces suspicion.

13. Use frozen Russian assets for reconstruction

Original (as reported by Reuters on Nov. 24, 2025, citing senior U.S. officials involved in the drafting):

The draft called for more than $100 billion in frozen Russian central bank assets to be applied directly to Ukraine’s reconstruction needs under a U.S.-guided structure.

Explanation:

Legally bold and politically popular in the West, this shifts the financial burden off U.S./EU taxpayers and onto Russia. Moscow, however, views seizure of sovereign assets as economic warfare.

Amended:

Retained; now structured under joint U.S.–EU governance, improving legitimacy.

U.S. reaction to amendment:

Very supportive — strengthens Western coordination.

Russia reaction to amendment:

Extremely negative; calls it “financial piracy.”

Strategic impact:

Provides Ukraine a reliable, long-term reconstruction mechanism.

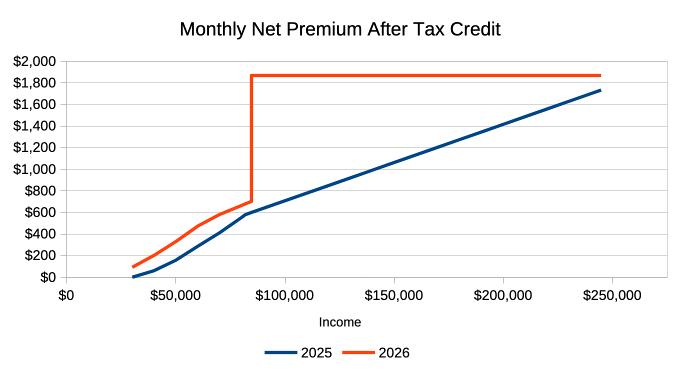

14. Automatic sanctions relief for Russia

Original (as reported by The Washington Post on Nov. 24, 2025, citing diplomats familiar with the proposal):

The draft included “automatic rollback” of sanctions as Russia met milestones.

Explanation:

This makes Russia’s path out of sanctions predictable, but allows for manipulation — partial compliance could unlock major relief.

Amended:

Automatic relief removed; sanctions relief becomes conditional and discretionary.

U.S. reaction:

Positive — retains leverage.

Russia reaction:

Negative — loses guaranteed benefits.

Strategic impact:

Prevents premature or undeserved sanctions relief.

15. Long-term U.S.–Ukraine economic integration

Original (as reported by ABC News on Nov. 23, citing negotiators in Geneva):

Outlined multi-decade plans for economic partnership in energy, technology, agriculture, and infrastructure.

Explanation:

Anchors Ukraine into the Western economic system long-term, reducing reliance on Russia.

Amended:

Retained and expanded to include the EU as a full partner.

U.S. reaction:

Strongly supportive.

Russia reaction:

Deeply negative — sees it as a permanent Western pivot.

Strategic impact:

Makes Ukraine structurally Western in its economic orientation.

16. Restore Russia’s access to SWIFT and global banking

Original (as reported by Reuters on Nov. 24, citing U.S. officials):

Proposed allowing Russia back into SWIFT if certain conditions were met.

Explanation:

Access to global banking is a top Russian priority; it would ease financial isolation.

Amended:

Reinstatement is deferred indefinitely, tied to full verified compliance.

U.S. reaction:

Supports delaying relief.

Russia reaction:

Highly negative — wants early SWIFT access.

Strategic impact:

Maintains financial pressure on Russia.

17. Ukraine restores Russian transit corridors

Original (as reported by The Guardian, Nov. 24, citing European negotiators):

Suggested reopening Ukrainian transit routes for Russian goods.

Explanation:

Early restoration benefits Russia economically without requiring Russian withdrawals.

Amended:

Transit rights now tied to full compliance and verified steps.

U.S. reaction:

Supportive — Ukraine should not ease Russian logistics prematurely.

Russia reaction:

Disappointed — early transit was economically attractive.

Strategic impact:

Strengthens Ukrainian leverage in negotiations.

18. International monitoring of Ukrainian elections

Original (as reported by ABC News on Nov. 23, citing diplomats in Geneva):

Included language pushing for internationally monitored elections in Ukraine.

Explanation:

Although transparency is good, mandating externally supervised elections can appear intrusive and undermine Ukrainian sovereignty.

Amended:

Election oversight now voluntary, at Ukraine’s discretion.

U.S. reaction:

Supportive — respects Ukraine’s democratic processes.

Russia reaction:

Likely negative — Russia hoped mandated elections could weaken Kyiv politically.

Strategic impact:

Protects Ukraine’s political independence and legitimacy.

IV. HUMANITARIAN POINTS

19. Return deported Ukrainian children

Original (as reported by Reuters on Nov. 24, 2025, citing humanitarian negotiators):

Russia required to repatriate Ukrainian children relocated to Russia or occupied territories.

Explanation:

Among the clearest alleged war crimes of the conflict, with thousands of children documented as forcibly transferred.

Amended:

Strengthened — return of children becomes an early, non-negotiable prerequisite.

U.S. reaction:

Very supportive — moral and legal necessity.

Russia reaction:

Resistant — Russia uses children for propaganda and leverage.

Strategic impact:

Crucial humanitarian and moral benchmark.

20. Comprehensive POW exchange

Original (as reported by ABC News and the Kyiv Independent during Geneva coverage):

A full-for-full exchange of all prisoners held by both sides.

Explanation:

A humanitarian priority for both populations; reduces suffering and builds early trust.

Amended:

Retained fully.

U.S. reaction:

Supportive.

Russia reaction:

Mixed — wants to retain leverage over Ukrainian POWs.

Strategic impact:

Creates a foundation for confidence-building.

21. Humanitarian corridors

Original (as reported by The Guardian, citing negotiation summaries):

Safe routes for civilians during ceasefire implementation.

Explanation:

Essential for reducing civilian harm; however, Russia has a track record of violating corridors.

Amended:

Retained unchanged.

U.S. reaction:

Supportive.

Russia reaction:

Publicly supportive, but implementation doubtful.

Strategic impact:

Reduces humanitarian risk and civilian casualties.

22. Family reunification rights

Original (as reported by Reuters and ABC News):

Both sides must restore rights for families separated by war, deportation, or evacuation.

Explanation:

Addresses long-term trauma and recovery; facilitates civil society rebuilding.

Amended:

Retained without changes.

U.S. reaction:

Positive.

Russia reaction:

Neutral — low political cost.

Strategic impact:

Supports social recovery and humanitarian stability.

V. GOVERNANCE & ENFORCEMENT POINTS

23. International observers along the ceasefire line

Original (as reported by Reuters on Nov. 24, 2025, citing two European security officials familiar with the draft):

The draft called for a multinational observer mission with authority to monitor the ceasefire line and document violations.

Explanation:

Observers help verify compliance and prevent covert advances. Russia has historically restricted observer access in occupied territories (e.g., OSCE in Donbas), making this a contentious but essential provision.

Amended:

Retained, explicitly under a multinational mandate with negotiated but broader access.

U.S. reaction:

Supportive — transparency strengthens enforcement.

Russia reaction:

Likely resistant — prefers to control outside access.

Strategic impact:

Improves verification and limits the ability of either side to cheat undetected.

24. Multinational monitoring of violations

Original (as reported by The Guardian on Nov. 24, citing European diplomats briefed on the negotiations):

The plan proposed a multi-state monitoring body using drones, satellite imagery, and on-the-ground reports to verify compliance.

Explanation:

Such monitoring reduces misinformation and creates a shared fact base. Russia dislikes multilateral oversight because it weakens Moscow’s ability to manipulate the narrative.

Amended:

Retained; cooperative monitoring emphasized.

U.S. reaction:

Approves — ensures shared responsibility and consistent reporting.

Russia reaction:

Negative — Russia prefers bilateral arrangements where it has greater leverage.

Strategic impact:

Hardens enforcement and helps maintain credibility of ceasefire reporting.

25. Annual compliance review conference

Original (as reported by ABC News on Nov. 23, citing negotiators):

The draft proposed yearly conferences where signatories evaluate compliance and discuss violations.

Explanation:

Provides predictability and structured dialogue, but can become symbolic if enforcement lacks teeth.

Amended:

Still present but decisions are advisory, not binding.

U.S. reaction:

Accepts — keeps diplomacy ongoing.

Russia reaction:

Unenthusiastic — dislikes public scrutiny.

Strategic impact:

Enables recurrent dialogue while preventing deadlock-inducing requirements.

26. Sanctions snap-back mechanism

Original (as reported by Reuters on Nov. 24, citing U.S. officials):

Included automatic reinstatement of sanctions if Russia violated terms.

Explanation:

Automatic snap-back is a strong deterrent, but Russia views it as a system that traps them in sanctions indefinitely.

Amended:

Snap-back retained but now includes political discretion rather than mechanical triggers.

U.S. reaction:

Approves — balances enforcement with diplomatic flexibility.

Russia reaction:

Strongly negative — ensures sanctions remain a lingering threat.

Strategic impact:

Maintains pressure while allowing room for diplomacy.

27. No legal immunity for Russian officials

Original (as reported by The Washington Post on Nov. 24, citing diplomatic officials):

The earliest drafts included discussions of legal immunities for Russian officials involved in wartime decisions.

Explanation:

Amnesty might entice Russia but violates accountability norms, clashes with ICC investigations, and is politically impossible in Ukraine and the West.

Amended:

All immunity language was removed entirely.

U.S. reaction:

Strongly supportive — aligns with Western legal principles.

Russia reaction:

Angry — immunity is coveted by the Kremlin elite.

Strategic impact:

Preserves war-crimes accountability and international legal norms.

28. Proposed 10–20 year non-aggression treaty

Original (as reported by ABC News on Nov. 23, citing negotiators in Geneva):

The draft proposed a long-term treaty preventing either side from using military force for 10–20 years.

Explanation:

Although symmetrical on paper, it locks Ukraine into accepting the status quo while allowing Russia to consolidate control, rearm, and pressure Ukraine through non-military means.

Amended:

Recast as “mutual security guarantees” without requiring neutrality, troop caps, or long-term no-force pledges.

U.S. reaction:

Supportive — avoids freezing territorial losses.

Russia reaction:

Negative — loses the ability to freeze gains permanently.

Strategic impact:

Prevents de facto acceptance of Russian occupation for decades.

LAYPERSON-FRIENDLY CONCLUSION

(Rewritten with qualifiers, sources, and clarity)

After evaluating the original 28-point framework and the revised 19-point version, here is what a normal reader should understand:

1. The original plan leaned heavily toward Russia — and was unworkable.

It would have forced Ukraine to give up territory, military capacity, and future NATO membership. European and Ukrainian officials described it as too close to the Kremlin’s demands. It was never going to be accepted.

2. The amended plan fixes almost all the unacceptable elements.

It removes forced concessions, takes out neutrality clauses, eliminates troop caps, and preserves Ukraine’s sovereignty.

3. Russia likely dislikes most of the amendments.

Kremlin spokesperson Dmitry Peskov said (Reuters, Nov. 24):

“We have seen no acceptable proposal that recognizes the new realities.”

“New realities” = Russia’s illegal annexations.

4. Ukraine supports the direction of the amendments.

President Zelenskyy publicly stated (ABC News, Nov. 23):

“Ukraine will never accept any agreement that legitimizes Russian occupation.”

Removing concessionary elements aligns the plan with Ukraine’s red lines.

5. Ukraine cannot likely fight indefinitely without U.S. support.

NATO Commander Cavoli told Congress (April 2024):

“Without U.S. assistance, Ukraine’s ability to defend itself would be severely compromised.”

CIA Director William Burns warned (May 2024):

“There is a very real risk that the Ukrainians could lose on the battlefield” if aid stops.

These statements are public and authoritative.

6. If U.S. aid drops substantially, Russia likely gains the upper hand long-term.

Not overnight — but gradually and decisively.

Russia has:

- larger population

- greater industrial output

- entrenched defensive lines

- artillery dominance

Ukraine has determination — but not unlimited resources.

7. This is why diplomacy is coming back into focus.

Not to surrender Ukraine, but to prevent:

- a Russian victory,

- an endless war,

- and political collapse of Western support.

The amended framework is not ideal.

But it tries to balance sovereignty, fairness, and political reality.

VI. U.S. POLITICAL REACTIONS (REPUBLICANS + DEMOCRATS)

1. Republican Reaction

Republicans are divided, but not in the ways some assume.

1A. National-Security Republicans (Graham, Sullivan, McConnell, Cornyn)

This group strongly supports Ukraine and views a frozen conflict as a strategic victory for Russia.

Sen. Lindsey Graham said (Feb. 28, 2024):

“A freeze is a win for Putin.”

Their view of the amended framework:

- Approve removal of Russian-concession terms

- Support conditional sanctions

- Oppose freezes that lock in Russian gains

- Back multinational monitoring

Bottom line: Ukraine must survive; Russia must not be rewarded.

1B. “America First” Republicans

This faction is skeptical of unlimited Ukraine aid and emphasizes domestic priorities.

Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene said (2023):

“Ukraine is not the 51st state.”

Their view of the amended framework:

- Prefer a ceasefire that reduces U.S. spending

- Support negotiations sooner rather than later

- Oppose long-term U.S. guarantees

- Mixed on sanctions (some favor rollback)

Bottom line: America should not carry the burden indefinitely.

2. Democratic Reaction

Democrats also split but align more closely overall.

2A. Mainstream Democrats (Biden administration, Senate Democrats)

They see support for Ukraine as essential to global stability.

President Biden said (Dec. 2023):

“If we walk away, Ukraine will lose — and Russia will win.”

Their view of the amended framework:

- Strongly support removal of territorial concessions

- Insist sanctions stay conditional

- Oppose forced neutrality

- Cautious about freezes

- Support humanitarian and oversight elements

Bottom line: Protect Ukraine, deter Russia, maintain NATO unity.

2B. Progressive Democrats

More focused on humanitarian outcomes and ceasefires.

Their view:

- Support humanitarian provisions

- Support ceasefire exploration

- Oppose rewarding Russia

- Doubt long-term military solutions

Bottom line: End suffering; avoid endless war.

3. Rare Bipartisan Agreement

Despite deep divisions, both parties agree on these fundamentals:

- No forced territorial concessions

- No immunity for Russian officials

- No automatic sanctions relief

- Ukraine remains sovereign

- A Russian victory would destabilize Europe and embolden China

This is why the amended framework — not the original — fits within Washington’s political lanes.

4. Where They Differ

Republicans (America First):

- Aid fatigue

- Want early diplomacy

- Less willing to commit long-term

Democrats (mainstream):

- Support continued aid

- Fear a Russian victory

- More cautious about ceasefires

Progressives:

- Want humanitarian-driven talks

- Skeptical of military-first approaches

5. What This Means for the Framework

The original 28-point plan would have been dead on arrival.

Too Russia-friendly, too destabilizing, impossible to sell in Congress.

The amended 19-point framework is now politically survivable.

Not ideal, not complete, but far more balanced.

Russia is still unlikely to accept it now —

but if battlefield dynamics or internal pressures change,

this may become the foundation for a future settlement.

FINAL BOTTOM-LINE SUMMARY

- The revised framework is fairer but not yet enforceable.

- It removes injustices for Ukraine but adds no real leverage over Russia.

- Ukraine needs continued U.S. support — and that support is politically fragile.

- Russia is unlikely to make concessions unless pressured by events.

- The framework is less about immediate peace and more about shaping the eventual terms when the war’s dynamics force all sides to reconsider.

**VII. Is the U.S. Preparing to Pivot Its Ukraine Policy?

The Signs, the Signals, and the Real Motive Question**

Even after the amended 19-point framework is cleaned up and made more balanced, one hard question remains:

If this plan doesn’t really force Russia to do anything differently,

why did U.S. strategists push it so hard?

Is the real target actually Ukraine?

Based on public reporting, official testimony, and how the plan evolved, it appears the United States may be preparing, slowly and quietly, to pivot its Ukraine policy from “open-ended support for victory” toward “support tied to an eventual political settlement.”

Not an announced pivot. Not an official doctrine. But the direction of travel.

1. The 28-Point Plan as a Signal — Not Just a Draft?

According to Reuters, The Washington Post, and ABC News, the original 28-point plan was drafted by U.S. officials and presented to Ukraine and European allies only after it was largely formed.

It:

- froze Russian gains in place

- contemplated recognition or acceptance of occupied territory

- constrained Ukraine’s NATO path

- capped Ukraine’s armed forces

- offered structured sanctions relief to Russia

European officials told The Washington Post privately that the plan looked too close to what Moscow wanted and that they had not been fully briefed before it was floated.

That doesn’t look like a document written solely to comfort Kyiv. It looks like a document written to test the limits of what Ukraine and Europe might swallow if pushed hard enough.

2. The Refined 19-Point Plan: Cleaning Up Optics, Not Creating Leverage

After sharp pushback, the U.S. and Ukraine worked on a “refined” 19-point framework in Geneva. Reuters and other outlets report that the most controversial items (territorial concessions, NATO ban, troop caps, immunity, automatic sanctions relief) were removed.

This made the plan:

- more defensible in Kyiv

- more acceptable in Europe

- more survivable in Washington

But crucially, the refinements do not add new, immediate costs for Russia:

- no mandatory withdrawals

- no timelines for de-occupation

- no hard enforcement measures that bite Moscow now

The revised framework is fairer, but it is not stronger in terms of pressure on Russia.

That is consistent with a U.S. posture of:

“We’re not ready to force Russia yet; we’re starting by shaping what Ukraine will eventually be expected to accept.”

3. Open Evidence of Pressure on Ukraine

The strongest clue that this plan is being used more on Ukraine than on Russia comes from reporting about the Thanksgiving deadline.

According to The Washington Post, U.S. officials told Ukrainian counterparts that if they did not sign onto the plan by Thanksgiving, they risked losing future U.S. support.

If accurate, that is not a message to Moscow. That is a lever applied to Kyiv.

It supports the intuition of many people:

This framework may function less as a tool to squeeze Russia, and more as a way to start “lowering the hammer” on Ukraine — gently at first, but clearly.

Washington cannot easily compel Moscow. It can, however, condition aid and political support to Kyiv.

4. U.S. Intelligence Messaging: Setting the Stage

At the same time these frameworks surfaced, U.S. intelligence and military leaders have been warning out loud about Ukraine’s dependence on U.S. support.

- CIA Director Bill Burns has said there is “a very real risk that the Ukrainians could lose on the battlefield” without additional aid, stressing that Russia has “regained the initiative” as Ukrainian ammunition shortages mount.

- NATO Commander Gen. Christopher Cavoli has testified that without U.S. assistance, Ukraine’s ability to defend itself “would be severely compromised,” warning about artillery ratios that could reach 10:1 in Russia’s favor.

These statements serve a double purpose:

- Justify supplemental aid in the near term

- Signal that Ukraine cannot assume indefinite U.S. support

That is exactly the environment in which a political framework gains weight: when military victory looks uncertain and open-ended war looks unsustainable.

5. Two Plausible Interpretations of U.S. Motives

My question to AI gets to the heart of intent. There are at least two plausible behavior.

Interpretation 1: Softly Conditioning Ukraine for an Eventual Settlement

Under this view, U.S. strategists:

- know Russia won’t concede in the short term,

- know Europe is fatigued,

- know U.S. political patience is limited,

- know Ukraine cannot reconquer all territory,

so they begin to:

- establish what a “reasonable” endgame might look like,

- socialize those ideas with Kyiv and allies,

- use the framework (and quiet deadlines) to signal that support may increasingly be tied to movement toward a political process.

In this interpretation, the framework is primarily aimed at Ukraine, not Russia. It creates a normative box:

“If you reject this, you’re the one rejecting peace.”

That is very close to what you articulated as “lowering the hammer on Ukraine.”

Interpretation 2: Laying Track for a Future Moment

Another, slightly softer reading is that:

- The U.S. knows the conditions for a settlement are not yet present.

- It expects military and political conditions to change (in Russia, Ukraine, Washington, or Europe).

- It wants to have a detailed framework ready for that moment so that talks don’t start from zero.

Here, the framework is a pre-negotiation template, not a real-time peace plan.

But even in this scenario, the document still functions as a subtle constraint on Ukraine, signaling:

“These are roughly the lines along which we, your main backer, can live with a settlement someday.”

6. Does Any of This Mean the U.S. “Wants” Ukraine to Lose?

No — it does not necessarily mean that.

More likely, it means U.S. strategists:

- no longer fully believe Ukraine can achieve a complete military victory (recovering all territory, including Crimea),

- want to protect Ukraine from total defeat,

- want to limit Russian gains,

- but also want to avoid endless, open-ended spending and escalation risks.

So they try to carve out a future where:

- Ukraine survives as a sovereign state,

- Russia does not get everything it wants,

- the war doesn’t go on forever,

- and the U.S. is not writing huge checks indefinitely.

In that sense, the framework is not pro-Russian — but it may be less pro-Ukrainian than earlier rhetoric suggested.

7. The Hard Reality My Question Exposes

What bothers me — and rightly so — is that:

- The amended plan demands very little from Russia right now,

- while it begins to shape and limit the range of acceptable options for Ukraine,

- and U.S. officials have reportedly used it as leverage on Kyiv (with warnings about future support).

That strongly suggests the framework functions more as:

A tool for managing Ukraine’s expectations and future choices

than as:

A tool for forcing Russia to change its behavior.

That’s the “real motive” concern, stated plainly.

And until there is real leverage on Russia — military, economic, political, or diplomatic — Moscow has little incentive to treat this framework as anything more than a document on someone else’s desk. The next step to watch is a likely US confrontation with Ukraine. LFM

You must be logged in to post a comment.