Leaving the City Better: Leadership, Limits, and the Question of a Bridge Too Far

A collaboration between Lewis McLain & AI

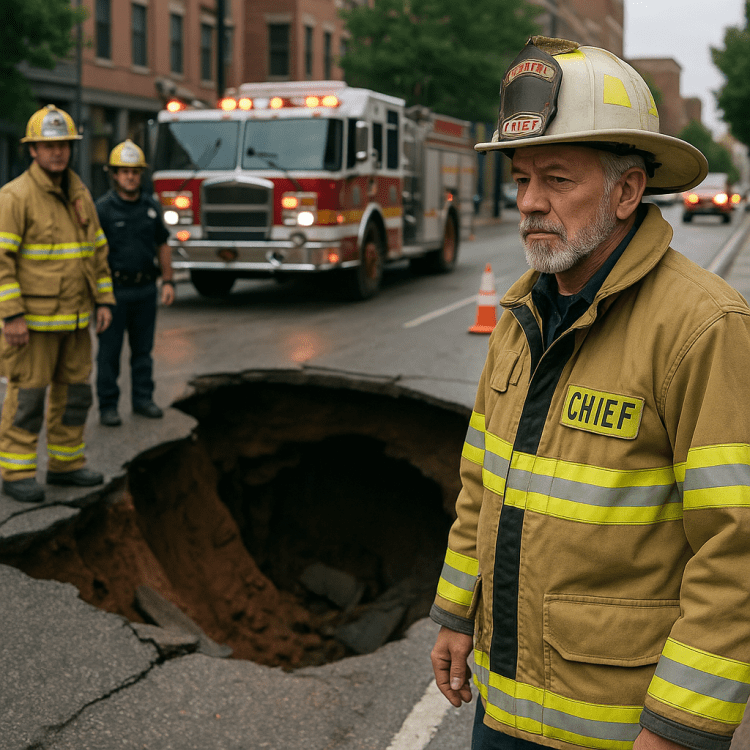

Leaders inherit messes. They step into offices burdened by deferred maintenance, ignored threats, regulatory capture, and systems quietly bent by special interests. In such a world, passivity does not preserve stability; it preserves neglect. Action becomes the moral baseline, not the exception. The enduring civic question is not whether leaders should push, but how far pushing remains stewardship rather than overreach.

The ancient Greek civic pledge offers a compass: leave the city better than you found it. Public life is stewardship across generations. Authority exists to repair what neglect erodes and to confront what avoidance normalizes. The statesman acts not for comfort, but for continuity—aware that problems ignored do not stay small.

This is where leadership grows hard. Entrenched interests organize precisely because complexity protects them. Manipulation thrives in delay. Incentives reward stasis. Gentle pressure rarely unwinds decades of avoidance. Leaders who push against these forces often look abrasive in real time, not because ego drives them, but because reform disturbs equilibria that were never healthy to begin with.

The phrase “a bridge too far” sharpens this tension. It enters common language through Cornelius Ryan’s account of Operation Market Garden in A Bridge Too Far. The plan is bold and morally urgent—end the war sooner, save lives—but it asks reality to cooperate with optimism. One bridge lies just beyond what logistics, intelligence, and time can support. The failure is not daring; it is miscalculation. The lesson is not “do nothing.” It is “know the load.”

Applied to leadership, the metaphor cuts both ways. Societies stagnate when leaders merely manage decline. Yet institutions exist for reasons that are not always cynical. Some limits preserve legitimacy, trust, and continuity—the invisible infrastructure of a functioning republic. The craft of leadership lies in distinguishing protective limits from self-serving barriers, then pressing the latter without snapping the former.

Seen through this lens, modern leaders often operate in the present tense of pressure. They test boundaries, confront norms, and treat friction as evidence of movement. That posture can be corrective when systems have grown complacent. It can also be hazardous when escalation outruns institutional capacity or public trust. A bridge does not fail the first time it is stressed; it fails after stress becomes routine.

This is where Donald Trump enters the conversation—not as verdict, but as caution. Trump governs with explicit confrontation. He challenges norms openly, personalizes conflict, and compresses long-delayed debates into immediate contests. Supporters see overdue action against captured systems. Critics see erosion of the trust that makes systems work at all. Both readings coexist because the pressure is real and the inheritance is heavy.

The wondering question is not whether such pressure is justified—it often is—but whether its sequencing and tone preserve the very institutions meant to be improved. The post-election period after 2020 brings the metaphor into focus. Legal challenges proceed as allowed; courts rule; states certify. Rhetoric, however, accelerates beyond evidence, and persuasion shades toward insistence. The bridge becomes visible. Not crossed decisively, but clearly approached. The risk is not a single act; it is precedent—teaching future leaders that legitimacy can be strained without immediate collapse.

January 6 stands as a symbolic edge of that bridge. Whatever one concludes about intent, the episode reveals an old truth: rhetoric travels faster than control. When foundational processes are publicly contested, leaders cannot always govern how followers translate suspicion into action. The system endures—but at a cost to shared reality.

None of this denies the core point: leaders given a boatload of neglect are not obligated to be passive. Improvement demands pressure. But the Greek ideal pairs strength with sophrosyne—measured restraint guided by wisdom. The city is left better not by humiliating institutions, but by restoring their purpose; not by replacing trust with loyalty to a person, but by renewing confidence in processes that outlast any one leader.

So what does leadership require in a world of manipulation and special interests?

It requires action, because neglect compounds.

It requires push, because stagnation corrodes.

It requires listening, because limits exist for reasons.

It requires calibration, because strength without proportion becomes its own form of neglect.

A bridge too far is rarely obvious in the moment. It announces itself later—through fragility, cynicism, or precedent. The enduring task of leadership is to cross the bridges that must be crossed, stop short of those that should not, and leave the city—tested, repaired, and steadier—better than it was found.

You must be logged in to post a comment.