The Hinge: Saturday Night Looking at Sunday

A collaboration between Lewis McLain & AI

There is a strange hour each week when the noise thins and the future begins to whisper.

Saturday night is not simply the end of leisure. It is not yet obligation. It is a hinge in time — a narrow corridor where the past week and the coming week briefly face each other.

You can feel it if you sit still long enough.

The music softens. The group texts slow. The sky turns darker than it needs to. And somewhere in the mind, a quiet recalculation begins.

Sunday is approaching.

And with it, something much older than us.

The Human Invention of Pause

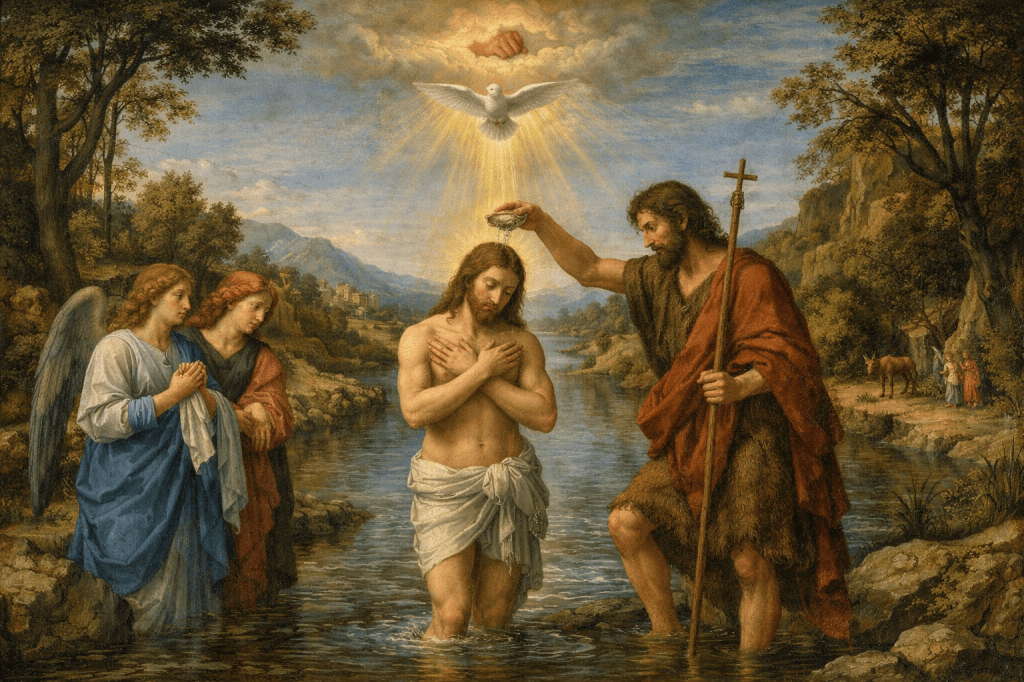

From the earliest pages of the Hebrew Scriptures, the idea of a structured pause appears. The Sabbath was not merely rest from labor. It was a deliberate interruption of production. A command to stop building, stop harvesting, stop calculating, and stop proving oneself.

That is radical.

In a world where survival once depended on constant vigilance, stopping required trust. The soil would not vanish overnight. The sky would not collapse because the plow rested.

Across centuries and cultures, humans have reinvented this idea in different forms. Markets close. Bells ring. Families gather. Screens dim. A society chooses to breathe.

Modern neuroscience now catches up with what ancient law already knew: chronic activation of the stress response system erodes cognition and health. Cortisol — the body’s alarm hormone — rises not only when chased by predators but when anticipating spreadsheets, performance reviews, and unresolved email threads.

The brain is an imagination machine. It simulates threats to prepare for them. Useful on the savannah. Less useful when the tiger is an inbox.

Saturday night is the moment when simulation often accelerates.

You are not yet working — but you are already working in your mind.

Anticipatory Stress: The Brain Cannot Tell the Difference

Psychologists call it anticipatory stress. The body reacts to what might happen tomorrow as if it is happening now. Heart rate increases. Muscles tense. Sleep fragments.

The nervous system evolved for immediacy. It does not distinguish cleanly between physical threat and abstract evaluation. A quarterly report can activate similar pathways as a rustling in tall grass.

This is not weakness. It is design.

But design needs ritual counterweights.

The ancient answer was Sabbath. The modern answer is less coherent. We substitute entertainment for restoration. We scroll instead of stilling. We stimulate the brain that needs calming.

Saturday night becomes a tug-of-war: one part of us reaching for distraction, another part feeling the gravity of the coming week.

The hinge creaks.

The Threshold State

Anthropologists use the term liminal to describe in-between states. A wedding ceremony marks the passage from single to married. A graduation marks the crossing from student to professional. New Year’s Eve bridges one calendar to another.

Saturday night is a recurring liminal space.

You are neither fully at rest nor fully at labor. You stand between identities: the relaxed self and the responsible self.

Humans behave differently at thresholds. Reflection increases. Meaning becomes sharper. Even architecture acknowledges this — doors, arches, and stairways are rarely neutral. They signal transition.

Saturday night is a psychological doorway.

And doorways invite decision.

The Weekly Vow

What if Sunday were not simply the last day of the weekend, but the renewal of a covenant with one’s calling?

Every profession — consultant, architect, teacher, engineer — demands attention and energy. Over time, purpose erodes under repetition. Fatigue dulls clarity. Cynicism creeps in quietly.

Yet the week resets whether we like it or not.

That reset can be passive or intentional.

A passive reset is dread.

An intentional reset is recommitment.

There is something powerful about treating Sunday as a vow renewal with one’s work and relationships. Not blind enthusiasm, but conscious consent. “I choose this again.”

Even marriages survive on renewal. Even institutions depend on reaffirmed mission statements. Why would the individual psyche be any different?

Saturday night is the drafting room for that vow.

Cyclical Time and Hope

Linear time moves in one direction. But human experience is structured in cycles — days, weeks, seasons, years.

Cycles offer hope because they imply return. After exhaustion comes rest. After winter comes growth. After failure comes another attempt.

The week is a small-scale laboratory of this principle.

Each Monday is disliked because it represents demand. Yet without Monday, there would be no rhythm, no narrative arc, no opportunity for progress.

The week functions like a flywheel. Momentum builds through repetition. Progress compounds not in dramatic leaps but in disciplined recurrence.

Saturday night stands at the edge of that flywheel.

It asks quietly: will you re-engage the mechanism?

If Excel Went to Church

Humor can illuminate truth better than solemnity.

Imagine Excel attending Sunday service.

Excel demands reconciliation. Every column must balance. Every formula must resolve. Circular references are unacceptable.

Grace, by contrast, refuses strict accounting. It credits where no debit exists. It forgives entries that cannot be reconciled.

And yet both pursue order.

The week we are about to enter will require accounting — time, effort, attention. But if the ledger becomes the only measure of worth, the soul shrinks to a spreadsheet.

Sunday, in its best form, interrupts pure calculation.

Saturday night is where the two systems argue gently.

The Physics of Beginning Again

There is something almost physical about the restart of a week. It feels like gravity shifting.

Time itself does not reset — that is a human invention. But human psychology responds powerfully to perceived fresh starts. Behavioral scientists have observed the “fresh start effect,” where temporal landmarks — a new month, a birthday, a Monday — increase goal-oriented behavior.

Why?

Because beginnings carry narrative energy. A blank page invites authorship.

Saturday night is the last paragraph before the blank page.

One can enter Sunday passively, dragged by inevitability. Or actively, with intention.

The difference is subtle but decisive.

The Quiet Telescope

Saturday night allows backward and forward vision simultaneously. You can examine the week behind — successes, failures, unfinished conversations — while glimpsing the week ahead.

This dual vision is rare.

Tuesday afternoon rarely invites existential reflection. Thursday at 2:30 p.m. does not whisper philosophy.

But Saturday night does.

It invites evaluation without immediate pressure.

That is a gift.

Civilizational Design

If entire societies abandon structured pauses, what happens?

Productivity increases temporarily. Output surges. Efficiency becomes idolized. Yet burnout accelerates. Families fragment. Meaning thins.

Rest is not laziness. It is structural reinforcement.

Bridges require expansion joints to absorb stress. Without them, fractures appear. Human systems are no different.

Sunday — whether religiously observed or secularly honored — functions as a societal expansion joint.

Saturday night is the moment when we decide whether we will use it wisely.

The Moral Act of Rest

There is a subtle moral dimension to rest.

To rest is to admit limitation. To acknowledge that you are not the axis upon which the universe turns. To concede that work will resume, but not endlessly.

In hyper-competitive environments, stopping feels irresponsible. Yet unbroken labor erodes judgment. Fatigue distorts decisions. Cynicism spreads.

Rest sharpens competence.

Saturday night whispers: you are finite.

Sunday responds: and that is acceptable.

The Anxiety and the Invitation

Yes, Sunday evening dread exists. The brain anticipates challenge.

But anticipation can be redirected.

Instead of rehearsing worst-case scenarios, one might rehearse readiness. Instead of simulating failure, simulate clarity.

The same imagination that conjures stress can construct resolve.

The hinge does not force direction. It offers choice.

The Strange Gift of Recurrence

Perhaps the most remarkable thing about Saturday night is that it will return.

Every seven days, without fail, the hinge reappears. A chance to recalibrate. A recurring opportunity to decide who you will be in the coming week.

Most of life’s grand turning points are rare. Graduation happens once. Retirement happens once. Milestones scatter sparsely across decades.

But this threshold arrives weekly.

The accumulation of small renewals shapes character more reliably than dramatic reinventions.

Standing in the Doorway

Saturday night is not glamorous.

It is not a holiday. It is not a crisis.

It is simply a doorway.

Yet doorways matter.

They orient us. They slow us. They mark passage.

Right now, as the evening deepens, you are standing in one.

Behind you is a completed week.

Ahead of you is an unwritten one.

You can drag the weight of the past forward. Or you can carry forward only the lessons.

You can dread the future. Or you can consent to it.

The hinge does not demand drama. It invites deliberation.

And that is enough.

Tomorrow will come regardless.

The only question Saturday night asks is this:

Will you step through consciously?

Because the week is about to begin again — and the remarkable thing about beginning again is that it never gets old.

You must be logged in to post a comment.