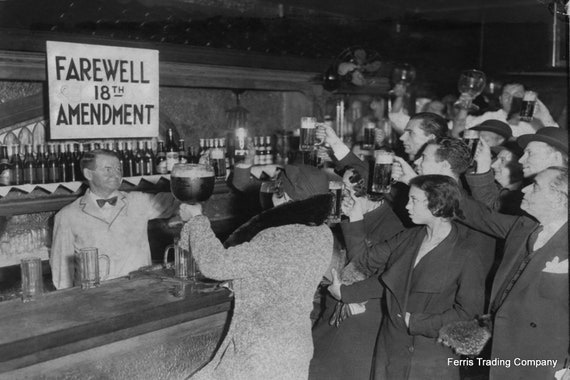

Prohibition: America’s Great Moral Experiment—and the Courage to Undo It

A collaboration between Lewis McLain & AI

Prohibition stands as one of the most instructive chapters in American public life, not because it failed, but because it failed honestly—with good intentions, broad support, and devastating unintended consequences. It is a case study in how a democratic society wrestles with morality, law, and human behavior, and what it means to admit error without abandoning principle.

The Moral Confidence of the Early 20th Century

Prohibition did not emerge from fanaticism. It grew from reform.

By the late 1800s and early 1900s, alcohol was deeply entangled with social harm. Excessive drinking contributed to domestic violence, workplace injuries, chronic poverty, and political corruption. Saloons were often tied to exploitative labor practices and machine politics. Women, in particular, bore the costs at home with little legal protection.

The temperance movement brought together an unlikely coalition: Protestant churches, progressive reformers, women’s organizations, public-health advocates, and rural voters who viewed alcohol as an urban vice. Their logic was straightforward: if alcohol is a primary cause of social disorder, then eliminating alcohol will reduce disorder.

It was a classic Progressive Era belief—social problems have technical solutions, and law can accelerate moral improvement.

In 1919, that belief crystallized into the 18th Amendment. In 1920, Prohibition went into effect nationwide.

The Reality That Followed

The policy did not collapse overnight. It unraveled systemically.

First, consumption adapted rather than disappeared. Alcohol did not vanish; it went underground. Speakeasies flourished in cities. Home distillation surged in rural areas. The quality of alcohol often worsened, leading to poisonings and long-term health damage. Drinking became less visible but more dangerous.

Second, crime industrialized. Prohibition transformed alcohol from a regulated commodity into a high-margin illicit product. Criminal organizations stepped in to meet demand. Smuggling routes expanded. Violence became a business tool. What had once been localized criminal activity evolved into national syndicates with unprecedented resources.

Third, respect for the law eroded. Millions of ordinary Americans violated Prohibition laws casually and repeatedly. Enforcement became selective, uneven, and corruptible. Police officers, judges, and politicians were placed in impossible positions—expected to enforce a law that large portions of the public openly rejected.

This was not a moral awakening; it was a credibility crisis. When law drifts too far from lived reality, it stops teaching virtue and starts teaching evasion.

The Cost No One Planned For

Perhaps the most damaging consequence was institutional.

Prohibition weakened faith in governance itself. Citizens learned that laws could be aspirational rather than practical, symbolic rather than enforceable. The gap between public virtue and private behavior widened. Hypocrisy became visible, and cynicism followed.

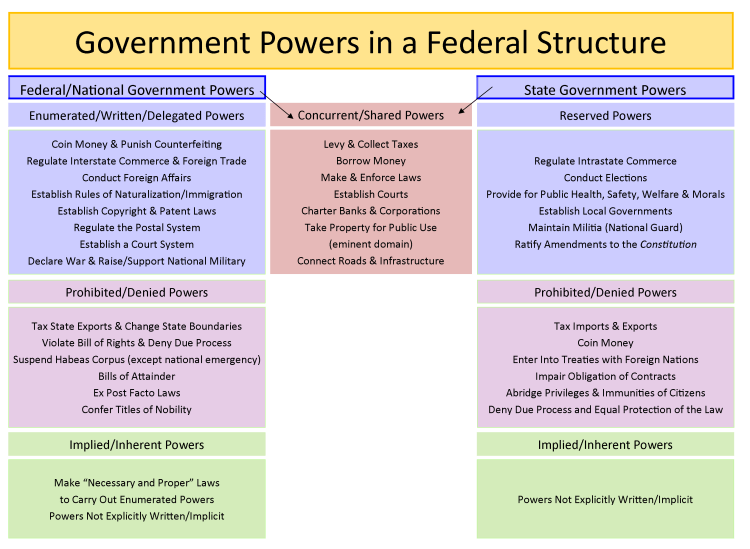

The federal government also discovered its limits. Enforcing Prohibition required resources far beyond what Congress was willing to provide. Borders proved porous. Local governments resisted. States interpreted enforcement unevenly. The machinery of the state strained under the weight of moral ambition.

Prohibition revealed a hard truth: the state is powerful, but not omnipotent—and pretending otherwise corrodes trust.

Why Repeal Was the Real Achievement

The repeal of Prohibition in 1933 is more significant than its enactment.

Governments are adept at creating policy. They are far less adept at reversing it. Repeal required lawmakers and citizens alike to concede that a deeply moral project had produced deeply immoral outcomes—not because the goals were wrong, but because the method was flawed.

The 21st Amendment did not celebrate excess. It acknowledged complexity.

Repeal restored regulation rather than chaos. Alcohol returned to legal channels where quality could be controlled, taxes collected, and criminal enterprises disrupted. Public health and safety improved not because Americans became virtuous overnight, but because law once again aligned with human behavior.

This was not moral surrender. It was moral realism.

The Enduring Lesson

Prohibition is often remembered as a joke—speakeasies, gangsters, bathtub gin. That memory misses the point.

The real lesson is about limits:

- The limit of law as a tool for shaping personal behavior

- The limit of enforcement in a free society

- The limit of certainty when policy meets culture

Prohibition teaches that durable reform moves in sequence: culture, then law—not the other way around. When law attempts to leapfrog culture, it creates shadow systems that are harder to govern and more dangerous than the original problem.

This is why Prohibition continues to echo in modern debates—over drugs, gambling, speech, and even technology. Different issues, same temptation: legislate the outcome rather than shape the conditions.

Why January 20 Matters

January 20, 1933, sits quietly in the historical calendar, but it marks a rare civic moment: a nation choosing correction over pride.

On a day associated with power transitions and public authority, the United States demonstrated something rarer than resolve—humility. It recognized that strength is not found in doubling down on a mistake, but in changing course before the damage becomes irreversible.

A Closing Reflection

Prohibition failed not because Americans rejected morality, but because morality cannot be mass-produced by statute. It must be cultivated, modeled, and supported by institutions that understand human nature rather than deny it.

That lesson is neither liberal nor conservative. It is simply hard-earned.

And it is one worth remembering—especially when certainty feels tempting and restraint feels weak.

The Day After: January 21, 1933 — When the Country Woke Up Sober

The repeal of Prohibition did not end with speeches or signatures. Its meaning unfolded the next morning.

On January 21, 1933—the day after repeal authority snapped back into place—America did not descend into revelry or collapse into vice. Instead, something quieter and more revealing happened: normal life resumed.

Bars did not instantly become lawless. Breweries did not flood streets with alcohol. Families did not unravel overnight. What returned was not excess, but legibility. Alcohol was no longer a rumor, a secret, or a criminal enterprise. It became visible again—regulated, taxable, inspectable, boring in the way lawful things usually are.

That boredom mattered.

From Illicit Thrill to Regulated Reality

Under Prohibition, alcohol carried the romance of defiance. Speakeasies thrived not merely because people wanted to drink, but because drinking had become a small act of rebellion. The day after repeal stripped alcohol of that mystique.

When something returns to daylight, it loses its glamour.

Legal beer—initially capped at low alcohol content—reappeared first. Breweries reopened cautiously. Distributors dusted off ledgers. States scrambled to design regulatory systems. Cities issued permits. Clerks checked licenses. Accountants sharpened pencils.

The machinery of ordinary governance restarted.

Crime syndicates, by contrast, began losing oxygen immediately. Without monopoly pricing and legal risk premiums, profits shrank. Violence became less “necessary.” The underground market contracted not because criminals found virtue, but because economics changed.

The day after repeal demonstrated a simple truth: regulation outcompetes prohibition when demand is durable.

A Subtle Restoration of Trust

Perhaps the most important change on January 21 was psychological.

For over a decade, millions of Americans had lived with a quiet contradiction: respecting the law in public while breaking it in private. The day after repeal lifted that tension. Citizens no longer had to pretend. Police no longer had to look away. Judges no longer had to perform moral arithmetic in sentencing.

The law once again described reality rather than denying it.

That alignment matters more than slogans. A legal system does not function on punishment alone; it functions on voluntary compliance. The day after repeal restored the possibility that citizens and institutions could once again inhabit the same moral universe.

What Did Not Happen

Equally instructive is what did not occur the day after repeal:

- There was no national spike in chaos

- No collapse of public morals

- No evidence that restraint had been holding civilization together by its fingernails

Life continued. People went to work. Families ate dinner. The republic survived the admission of error.

That absence of catastrophe is itself an argument.

Why This Matters for a Modern Reader

Publishing this essay the day after January 20 invites an intentional parallel.

January 20 is about authority—who holds it, how it is transferred, how it is justified. January 21 is about what authority does once the ceremony is over. The day after asks a harder question than the day of:

Does policy still make sense when the speeches stop?

Prohibition failed that test. Repeal passed it.

The day after repeal reminds us that responsible governance is not measured by how dramatic a law sounds at enactment, but by how quietly society functions once it is in force.

A Final Reflection to Close the Essay

The repeal of Prohibition did not make America virtuous. It made America honest—about human behavior, about enforcement limits, and about the difference between moral aspiration and civic design.

The day after repeal, the country woke up without a grand illusion—and discovered it could still stand.

That may be the most encouraging lesson of all.

You must be logged in to post a comment.