An Update on Drone Uses in Texas Municipalities

A second collaboration between Lewis McLain & AI

From Tactical Tools to a Quiet Redefinition of First Response

A decade ago, a municipal drone program in Texas usually meant a small team, a locked cabinet, and a handful of specially trained officers who were called out when circumstances justified it. The drone was an accessory—useful, sometimes impressive, but peripheral to the ordinary rhythm of public safety.

That is no longer the case.

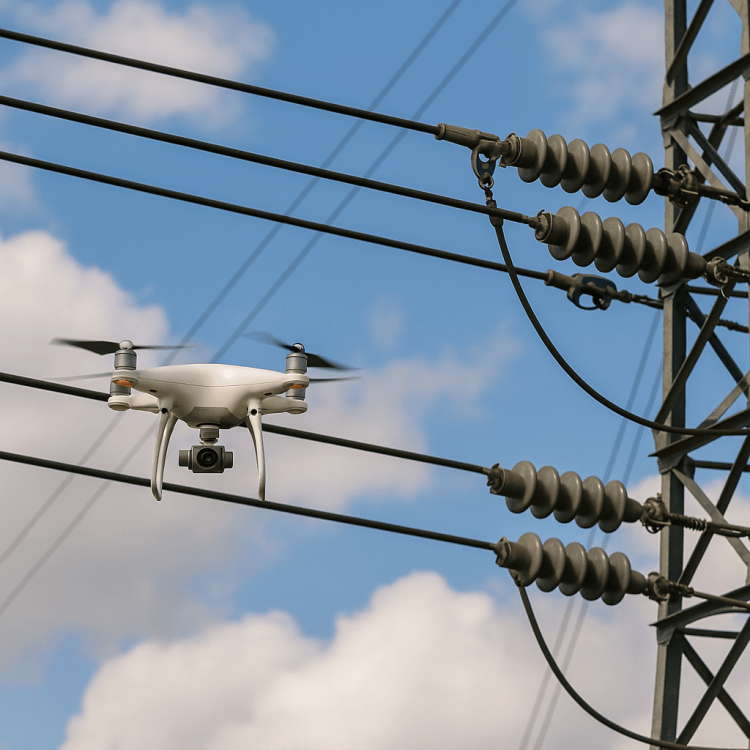

Across Texas, drones are being absorbed into the daily mechanics of emergency response. In a growing number of cities, they are no longer something an officer brings to a scene. They are something the city sends—often before the first patrol car, engine, or ambulance has cleared an intersection.

This shift is subtle, technical, and easily misunderstood. But it represents one of the most consequential changes in municipal public safety design in a generation.

The quiet shift from tools to systems

The defining change is not better cameras or longer flight times. It is program design.

Early drone programs were built around people: pilots, certifications, and equipment checklists. Today’s programs are built around systems—launch infrastructure, dispatch logic, real-time command centers, and policies that define when a drone may be used and, just as importantly, when it may not.

Cities like Arlington illustrate this evolution clearly. Arlington’s drones are not stored in trunks or deployed opportunistically. They launch from fixed docking stations, controlled through the city’s real-time operations center, and are sent to calls the way any other responder would be. The drone’s role is not to replace officers, but to give them something they rarely had before arrival: certainty.

Is someone actually inside the building? Is the suspect still there? Is the person lying in the roadway injured or already moving? These are small questions, but they shape everything that follows. In many cases, the presence of a drone overhead resolves a situation before physical contact ever occurs.

That pattern—early information reducing risk—is now being repeated, in different forms, across the state.

North Texas as an early laboratory

In North Texas, the progression from experimentation to normalization is especially visible.

Arlington’s program has become a reference point, not because it is flashy, but because it works. Drones are treated as routine assets, subject to policy, supervision, and after-action review. Their value is measured in response times and avoided escalations, not in flight hours.

Nearby, Dallas is navigating a more complex path. Dallas already operates one of the most active municipal drone programs in the state, but scale changes everything. Dense neighborhoods, layered airspace, multiple airports, and heightened civil-liberties scrutiny mean that Dallas cannot simply replicate what smaller cities have done.

Instead, Dallas appears to be doing something more consequential: deliberately embedding “Drone as First Responder” capability into its broader public-safety technology framework. Procurement language and public statements now describe drones verifying caller information while officers respond—a quiet but important acknowledgement that drones are becoming part of the dispatch process itself. If Dallas succeeds, it will establish a model for large, complex cities that have so far watched DFR from a distance.

Smaller cities have moved faster.

Prosper, for example, has embraced automation as a way to overcome limited staffing and long travel distances. Its program emphasizes speed—sub-two-minute arrivals made possible by automated docking stations that handle charging and readiness without human intervention. Prosper’s experience suggests that cities do not have to grow into DFR gradually; some can leap directly to system-level deployment.

Cities like Euless represent another important strand of adoption. Their programs are smaller, more cautious, and intentionally bounded. They launch drones to specific call types, collect experience, and adjust policy as they go. These cities matter because they demonstrate how DFR spreads laterally, city by city, through observation and imitation rather than mandates or statewide directives.

South Texas and the widening geography of DFR

DFR is not a North Texas phenomenon.

In the Rio Grande Valley, Edinburg has publicly embraced dispatch-driven drone response for crashes, crimes in progress, and search-and-rescue missions, including night operations using thermal imaging. In regions where heat, terrain, and distance complicate traditional response, the value of rapid aerial awareness is obvious.

Further west, Laredo has framed drones as part of a broader rapid-response network rather than a narrow policing tool. Discussions there extend beyond observation to include overdose response and medical support, pointing toward a future where drones do more than watch—they enable intervention while ground units close the gap.

Meanwhile, cities like Pearland have quietly done the hardest work of all: making DFR ordinary. Pearland’s early focus on remote operations and program governance is frequently cited by other cities, even when it draws little public attention. Its lesson is simple but powerful: the more boring a drone program becomes, the more likely it is to scale.

What 2026 will likely bring

By 2026, Texas municipalities will no longer debate drones in abstract terms. The conversation will shift to coverage, performance, and restraint.

City leaders will ask how much of their jurisdiction can be reached within two or three minutes, and what it costs to achieve that standard. DFR coverage maps will begin to resemble fire-station service areas, and response-time percentiles will replace anecdotal success stories.

Dispatch ownership will matter more than pilot skill. The most successful programs will be those in which drones are managed as part of the call-taking and response ecosystem, not as specialty assets waiting for permission. Pilots will become supervisors of systems, not just operators of aircraft.

At the same time, privacy will increasingly determine the pace of expansion. Cities that define limits early—what drones will never be used for, how long video is kept, who can access it—will move faster and with less friction. Those that delay these conversations will find themselves stalled, not by technology, but by public distrust.

Federal airspace rules will continue to separate tactical programs from scalable ones. Dense metro areas will demand more sophisticated solutions—automated docks, detect-and-avoid capabilities, and carefully designed flight corridors. The cities that solve these problems will not just have better drones; they will have better systems.

And perhaps most telling of all, drones will gradually fade from public conversation. When residents stop noticing them—when a drone overhead is no more remarkable than a patrol car passing by—the transformation will be complete.

A closing thought

Texas cities are not adopting drones because they are fashionable or futuristic. They are doing so because time matters, uncertainty creates risk, and early information saves lives—sometimes by prompting action, and sometimes by preventing it.

By 2026, the question will not be whether drones belong in municipal public safety. It will be why any city, given the chance to act earlier and safer, would choose not to.

Looking Ahead to 2026: When Drones Become Ordinary

By 2026, the most telling sign of success for municipal drone programs in Texas will not be innovation, expansion, or even capability. It will be normalcy.

The early years of public-safety drones were marked by novelty. A drone launch drew attention, generated headlines, and often triggered anxiety about surveillance or overreach. That phase is already fading. What is emerging in its place is quieter and far more consequential: drones becoming an assumed part of the response environment, much like radios, body cameras, or computer-aided dispatch systems once did.

The conversation will no longer revolve around whether a city has drones. Instead, it will focus on coverage and performance. City leaders will ask how quickly aerial eyes can reach different parts of the city, how often drones arrive before ground units, and what percentage of priority calls benefit from early visual confirmation. Response-time charts and service-area maps will replace anecdotes and demonstrations. In this sense, drones will stop being treated as technology and start being treated as infrastructure.

This shift will also clarify responsibility. The most mature programs will no longer center on individual pilots or specialty units. Ownership will move decisively toward dispatch and real-time operations centers. Drones will be launched because a call meets predefined criteria, not because someone happens to be available or enthusiastic. Pilots will increasingly function as system supervisors, ensuring compliance, safety, and continuity, rather than as hands-on operators for every flight.

At the same time, restraint will become just as important as reach. Cities that succeed will be those that articulate, early and clearly, what drones are not for. By 2026, residents will expect drone programs to come with explicit boundaries: no routine patrols, no generalized surveillance, no silent expansion of mission. Programs that fail to define those limits will find themselves stalled, regardless of how capable the technology may be.

Federal airspace rules and urban complexity will further separate casual programs from durable ones. Large cities will discover that scaling drones is less about buying more aircraft and more about solving coordination problems—airspace, redundancy, automation, and integration with other systems. The cities that work through those constraints will not just fly more often; they will fly predictably and defensibly.

And then, gradually, the attention will drift away.

When a drone arriving overhead is no longer remarkable—when it is simply understood as one of the first tools a city sends to make sense of an uncertain situation—the transition will be complete. The public will not notice drones because they will no longer symbolize change. They will symbolize continuity.

That is the destination Texas municipalities are approaching: not a future where drones dominate public safety, but one where they quietly support it—reducing uncertainty, improving judgment, and often preventing escalation precisely because they arrive early and ask the simplest question first: What is really happening here?

By 2026, the most advanced drone programs in Texas will not feel futuristic at all. They will feel inevitable.

You must be logged in to post a comment.