Confession of Beliefs, Faith, and Confidence

1. The Bible

I Believe

that the Bible is the inspired, trustworthy, and authoritative Word of God, the supreme guide for what I believe and how I live.

I Am Confident

because its manuscripts are preserved with extraordinary accuracy, its history confirmed by archaeology, its prophecies fulfilled in Christ, and Jesus Himself affirmed its truth. The Bible continues to transform lives and cultures across centuries, showing divine origin and power.

Scripture

2 Tim 3:16–17; 2 Pet 1:20–21; Ps 19:7–11; Ps 119:105; Matt 5:17–18; John 10:35; Luke 24:27.

2. God

I Believe

in one God—Father, Son, and Holy Spirit—eternal, holy, sovereign, and love.

I Am Confident

because creation, morality, and human longing point to a personal Creator. Only the triune God revealed in Scripture explains reality fully and satisfies the deepest needs of the heart.

Scripture

Ex 3:14; Ex 34:6–7; Deut 6:4; Isa 6:1–5; Ps 139; Acts 17:24–28; Matt 28:19; 2 Cor 13:14.

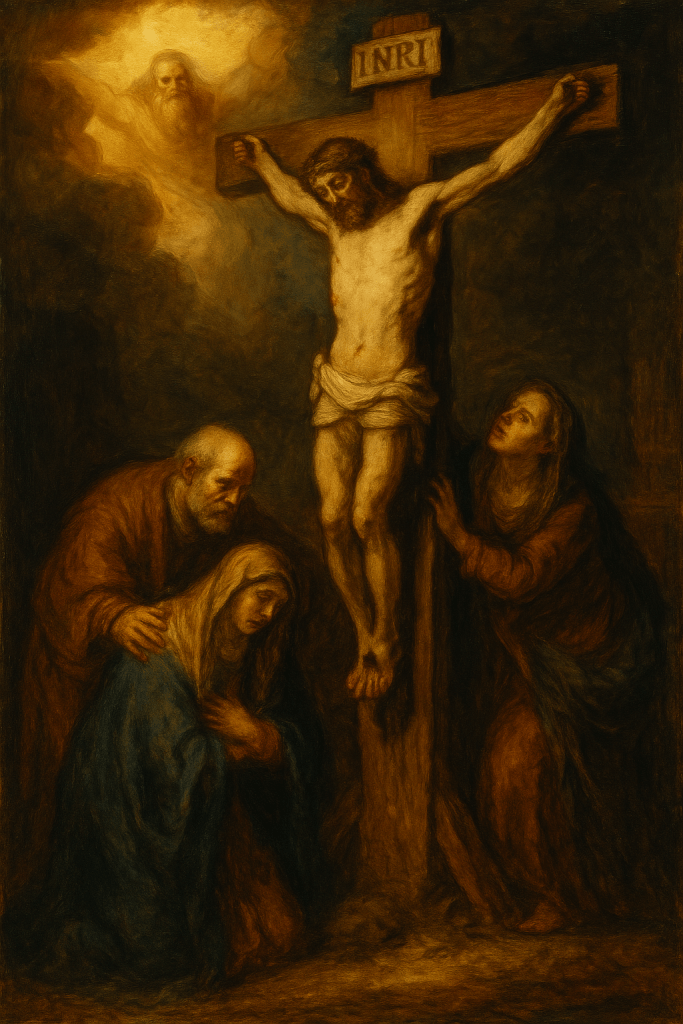

3. Jesus Christ

I Believe

that Jesus Christ is fully God and fully man, the eternal Son who became flesh, lived a sinless life, died for my sins, rose bodily from the dead, and reigns as Lord.

I Am Confident

because the evidence for His resurrection is overwhelming: eyewitnesses, empty tomb, transformed disciples, fulfilled prophecy, and the rise of the Church. No other religious figure has claimed and proved divinity as He did.

Scripture

John 1:1–14; Phil 2:5–11; Col 1:15–20; Heb 1:1–4; Isa 53:5; 2 Cor 5:21; Rom 3:21–26; 1 Cor 15:3–8; Matt 1:23.

4. The Holy Spirit

I Believe

in the Holy Spirit, the Lord and Giver of life, who convicts the world of sin, regenerates the sinner, indwells, seals, and sanctifies believers, distributes gifts for service, and produces fruit of holy character.

I Am Confident

because His transforming work is seen in changed lives across centuries and cultures, producing unity, gifts, and fruit beyond human ability. He continues to glorify Christ and empower the Church for mission.

Scripture

John 3:5–8; John 14:16–17, 26; John 16:7–15; Acts 1:8; Acts 5:3–4; Rom 8:9–16; 1 Cor 12:4–11; Gal 5:22–23; Eph 1:13–14.

5. Angels & Satan

I Believe

that God created His holy angels as servants and messengers, and that Satan and his demons are fallen angels who oppose Him but stand defeated at the cross and doomed for final judgment.

I Am Confident

because evil is not merely abstract but personal. Yet Christ triumphed at the cross, disarming the powers of darkness. Believers resist not in fear but in God’s strength, clothed with His armor.

Scripture

Heb 1:14; Ps 103:20–21; Gen 3; Matt 4:1–11; Luke 10:18; Eph 6:10–18; 1 Pet 5:8–9; Col 2:15; Rev 12:7–12.

6. Humanity & Life

I Believe

that man and woman were created in the image of God— to know Him, love Him, and reflect His glory.

Life is God’s sacred gift, beginning at the moment of conception.

The unborn are fearfully and wonderfully made, known and called by God before birth, and worthy of dignity, protection, and love.

Through sin, humanity fell, and now all have sinned and fall short of God’s glory.

Yet in Christ we are made new, restored as His image-bearers and called into fellowship with Him.

I Am Confident

because humanity’s uniqueness — conscience, creativity, worship, and love — cannot be explained apart from God’s image. Science affirms that life begins at conception, while Scripture insists on the dignity of every person. Christianity both exalts human worth and diagnoses human sin, giving the truest picture of man.

Scripture

Gen 1:26–28; Gen 2:7; Ps 8; Ps 139:13–16; Jer 1:5; Luke 1:41; Ex 21:22–25; Rom 5:12–19; Rom 3:23; Acts 17:26–28; 2 Cor 5:17.

7. Sin

I Believe

that sin is rebellion against God, corrupting every part of our being, separating us from His presence, and bringing death as its wage. But God, rich in mercy, forgives those who repent and cleanses us from all unrighteousness.

I Am Confident

because sin explains both personal failure and global brokenness. Scripture’s verdict that “all have sinned” matches reality. Yet God’s grace in Christ proves that sin’s curse is not the last word.

Scripture

Rom 3:9–23; Rom 6:23; Isa 59:2; 1 John 3:4; Jas 4:17; Rom 14:23; Ps 51; 1 John 1:9.

8. Salvation

I Believe

that salvation is by grace alone, through faith alone, in Christ alone.

By His mercy we are justified, adopted into God’s family, sanctified by His Spirit, and kept by His power until the day of glory.

I believe He who began a good work in me will carry it to completion at the day of Christ Jesus.

I Am Confident

because the gospel is grounded in fact, not feeling. The cross satisfies God’s justice; the resurrection guarantees life. Salvation rests in Christ’s finished work, not human effort, making assurance possible.

Scripture

Eph 2:1–10; John 3:16; Titus 3:4–7; Rom 5:1–11; Rom 8:1, 28–39; 2 Cor 5:17–21; John 10:28–29; Phil 1:6.

9. The Church, Lord’s Day, Marriage & Mission

I Believe

in the one holy Church, the body and bride of Christ, set apart for worship, fellowship, and mission.

We are a royal priesthood, called to proclaim His marvelous light.

Christ gave us baptism and the Lord’s Supper as signs of His grace and our covenant in Him.

We gather on the Lord’s Day to worship, rest, and renew our devotion.

The Church is sent to the nations, and every believer is called to witness, to make disciples, and to live as Christ’s ambassador.

I believe God created marriage as the covenant union of one man and one woman for life, a holy mystery reflecting Christ and His Church, the foundation for family, fruitfulness, and faithfulness.

I Am Confident

because the Church has endured through persecution and failure, yet thrives across cultures. Worship on the Lord’s Day strengthens believers in faith. Marriage continues to witness to God’s covenant love. Evangelism through ordinary Christians advances the gospel powerfully.

Scripture

Matt 16:18; Matt 28:18–20; Acts 2:42–47; Acts 20:7; Rev 1:10; 1 Cor 12; Eph 4:1–16; 1 Pet 2:9–10; Heb 10:24–25; 2 Cor 5:20; Eph 5:31–32; Gen 2:24; Matt 19:4–6; Heb 13:4.

10. Stewardship

I Believe

that all I have—time, talents, and treasure—belongs to God, entrusted to me as His steward.

I Am Confident

because the earth is the Lord’s, and I am His trustee. Faithful stewardship glorifies Christ, blesses others, and brings eternal reward.

Scripture

Ps 24:1; 1 Cor 4:2; 2 Cor 9:6–8; Matt 25:14–30.

11. Peace, Justice & Liberty

I Believe

that Christ calls me to seek peace, pursue justice, defend the oppressed, and love mercy.

I believe in religious liberty, that faith cannot be coerced, and that church and state are distinct under God’s authority.

I Am Confident

because God’s kingdom is righteousness and peace. Religious liberty protects conscience, allowing true worship. Justice and mercy flow from God’s heart and remain central to the Church’s witness in the world.

Scripture

Micah 6:8; Amos 5:24; Jas 1:27; Matt 5:9; Rom 12:18; Eccl 3:8; Matt 22:21; Rom 14:5; Gal 5:1.

12. The Future

I Believe

that Jesus Christ will return in glory, visibly and with power, to raise the dead, to judge the nations, and to make all things new.

The redeemed will dwell forever with God in the new heavens and the new earth, where righteousness, peace, and joy abound.

The wicked will face eternal separation from Him.

I Am Confident

because prophecy fulfilled in Christ’s first coming assures His second. The resurrection of Jesus is the pledge of our resurrection. Hope in eternity provides courage and joy for the present.

Scripture

Acts 1:11; Titus 2:13; 1 Cor 15:20–28, 50–58; 1 Thess 4:13–18; Matt 25:31–46; John 5:28–29; Rev 20:11–15; Rev 21:1–5; 2 Pet 3:10–13.

13. The New Covenant of Love

I Believe

in the new covenant that Jesus gave: to love the Lord my God with all my heart, soul, mind, and strength, and to love my neighbor as myself. On these commandments hang all the Law and the Prophets.

I Am Confident

because love fulfills the Law, and the Spirit empowers what the Law demands. The history of Christian love — in hospitals, schools, abolition, reconciliation — testifies to God’s presence in His people.

Scripture

Deut 6:5; Lev 19:18; Matt 22:37–40; John 13:34; John 15:12.

14. Assurance of Salvation and the Life Ever After

I Believe

that those who trust in Christ have eternal life and cannot be separated from the love of God.

At death the believer is present with the Lord, awaiting the resurrection of the body.

In the age to come, God will wipe away every tear, death shall be no more, and His people will dwell in His presence forever in glory.

I Am Confident

because Scripture promises that nothing can separate us from the love of God in Christ. Assurance rests not on feelings but on God’s promises, Christ’s finished work, and the Spirit’s witness. Jesus told the thief on the cross, “Today you will be with Me in Paradise.” Paul declared, “To be absent from the body is to be present with the Lord.” Revelation describes heaven as a restored creation: no curse, no sorrow, no night, for the Lamb is its light. This hope anchors the soul, conquers fear of death, and fills the believer with longing for eternity.

Scripture

Rom 8:38–39; John 10:28–29; John 14:1–3; Luke 23:43; 2 Cor 5:6–8; Phil 1:21–23; 1 Thess 4:16–17; Rev 21:3–4; Rev 22:1–5.

15. The Way of Salvation — Becoming a Christian

I Believe

that to become a Christian, a person must respond to God’s grace with repentance from sin and faith in Jesus Christ as Lord and Savior.

Salvation is not earned by works or religious effort but is received as a gift of grace.

Those who call on the name of the Lord will be saved, baptized as a public witness, and joined to the body of Christ.

I Am Confident

because Scripture clearly reveals the steps of response:

- Hearing the gospel of Christ crucified and risen (Rom 10:17).

- Repenting of sin and turning to God (Acts 2:38).

- Believing in the Lord Jesus Christ with the heart (Acts 16:31; John 3:16).

- Confessing Him openly as Lord (Rom 10:9–10).

- Being baptized in obedience as the sign of new life (Acts 2:41; Matt 28:19).

- Living as a disciple in fellowship with the Church, growing in faith and obedience (Acts 2:42).

This is the biblical pattern: by grace through faith, in Christ alone, sealed by the Spirit, demonstrated in repentance and baptism, and lived out in the community of believers.

Scripture

John 3:16; Acts 2:37–41; Acts 16:30–31; Rom 10:9–13, 17; Eph 2:8–9; Titus 3:4–7; 1 John 1:9; Matt 28:19–20.

Closing

This is my faith and my confidence—

what I believe and why I believe it.

Founded on God’s Word,

grounded in history,

confirmed by reason,

and lived by the Spirit’s power.

To God alone be glory,

forever and ever. Amen.

Sources:

- Suggested by Dr. Bobby Waite

- The Scriptures

- Paul E. Little

- Know What You Believe (1967) – a summary of essential Christian doctrines.

- Know Why You Believe (1968) – addressing questions and objections to the faith.

- The Baptist Faith and Message (2000)

- Compilation & Expansions by Lewis McLain & AI

You must be logged in to post a comment.