Psyche Revived by Cupid’s Kiss

A collaboration between Lewis McLain & AI (more from the three visits Linda & I had to the Louvre with high school students from Trinity Christian Academy).

Antonio Canova and the Awakening of the Soul

Introduction

Among the marble treasures of the Louvre Museum stands one of the most moving sculptures of all time — Psyche Revived by Cupid’s Kiss, carved by the Italian master Antonio Canova between 1787 and 1793. It depicts the mythological moment when the god Cupid (Eros) revives his beloved Psyche with a kiss, restoring her from deathlike sleep to life and love.

At once tender, idealized, and technically perfect, this masterpiece captures not only the beauty of myth but also the intellectual spirit of the Neoclassical age. For any student observer, it represents the perfect synthesis of form, feeling, and philosophy — a lesson in how art can make marble breathe.

1. The Artist and His Era

Antonio Canova (1757–1822) was born in Possagno, Italy, into a family of stonemasons. Trained in Venice and working in Rome, he became the undisputed master of the Neoclassical style, the artistic movement that sought to revive the order, harmony, and moral clarity of ancient Greece and Rome.

Canova’s art emerged during the Age of Enlightenment, a time when reason, science, and rediscovered antiquity guided intellectual life. Artists looked to classical sculpture for purity of line and noble simplicity. Against the emotional extravagance of the Baroque, Canova’s figures embodied balance, restraint, and serenity.

His goal, he once said, was to give marble the “appearance of living flesh” — and through meticulous polishing and proportion, he succeeded. His works, such as Perseus with the Head of Medusa and The Three Graces, stand as paragons of refinement and calm emotional depth.

2. The Myth of Cupid and Psyche

The story comes from Apuleius’s The Golden Ass (2nd century A.D.), one of the most enduring love myths of classical antiquity.

- Psyche, a mortal woman of exceptional beauty, arouses the jealousy of Venus (Aphrodite), who orders her son Cupid to make Psyche fall in love with a monster.

- Instead, Cupid himself falls in love with Psyche, visiting her each night unseen. When Psyche disobeys his order never to look at him, he vanishes.

- After many trials set by Venus, Psyche opens a box meant to contain beauty but instead releases a deadly sleep upon herself.

- Cupid finds her lifeless body, lifts her in his arms, and awakens her with a kiss.

- In the end, the gods grant Psyche immortality so she may be eternally united with Cupid.

The myth is a timeless allegory of the soul’s (psyche) awakening to divine love and eternal life — a theme that resonated deeply with both ancient philosophy and Christian symbolism.

3. Commission and Creation

Canova received the commission around 1787 from Colonel John Campbell, a British nobleman visiting Rome. The sculptor completed the work by 1793, using Carrara marble, prized for its pure white translucence.

He later produced a second version (1796), now in the Hermitage Museum, but the first — the Louvre version — remains the most celebrated. It was acquired by Joachim Murat, Napoleon’s brother-in-law, and entered the Louvre’s collection in 1824.

Canova personally oversaw every stage of its creation, using fine abrasives and oil to achieve an extraordinary surface polish. This allowed light to glide across the marble as if over living skin, enhancing the illusion of breath and movement.

4. Composition and Form

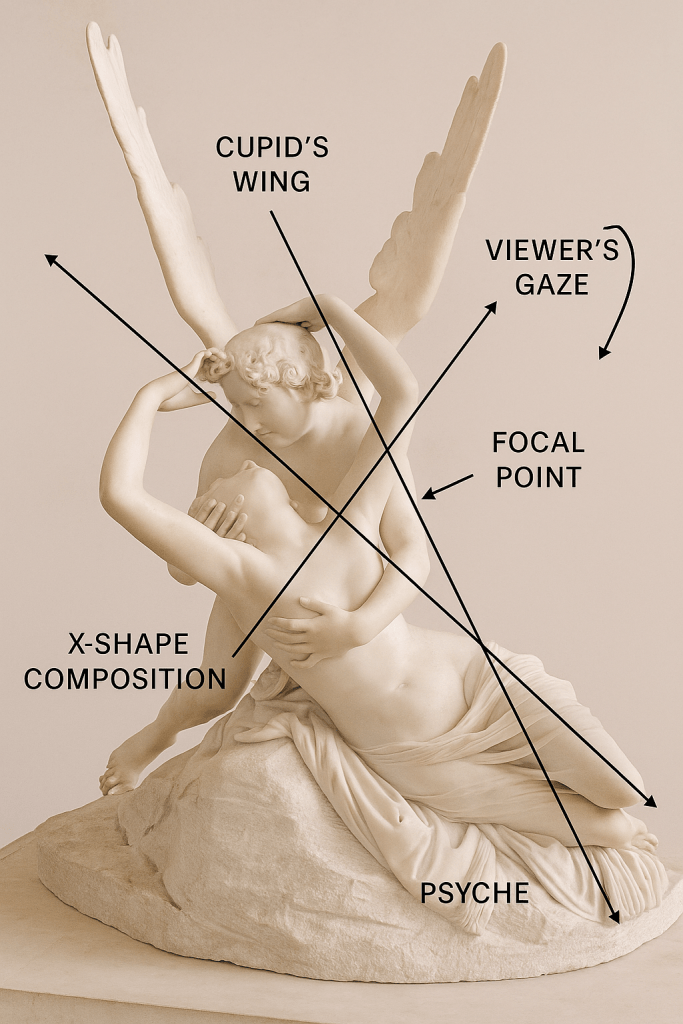

The sculpture captures the precise instant of awakening: Cupid bends over Psyche, supporting her head with one hand while their lips draw near. Psyche’s arms reach upward to encircle him, creating a perfect X-shaped composition — a dynamic cross of limbs and wings that binds the figures together.

Key features to observe:

- Cupid’s wings rise upward like an angelic halo, framing the scene and drawing the eye toward the couple’s faces.

- Psyche’s body arches in a graceful curve, suggesting both fragility and renewal.

- Their hands and faces form the emotional focal point — the intersection of life, love, and divine energy.

- The base of the sculpture, rough and unpolished, contrasts with the smooth flesh above, symbolizing the transition from earthly death to heavenly awakening.

In the educational diagram below, the X-shape composition and the diagonal lines of sight show how Canova directs the viewer’s gaze from Cupid’s wings to Psyche’s face and then downward through the drapery — a continuous flow of motion through stillness.

5. Symbolism and Interpretation

Canova’s sculpture is far more than an illustration of a myth — it is a philosophical meditation on love and the soul.

The moment of Psyche’s awakening becomes a symbol of spiritual rebirth. The butterfly, often associated with Psyche in classical art, represents transformation — the soul leaving its cocoon of mortality. Cupid, as divine love, breathes eternal life into that soul.

The composition’s diagonal tension embodies both physical energy and emotional ascent: the human yearning for the divine, the eternal dance between matter and spirit.

In Neoclassical thought, beauty was a moral force — the visible expression of virtue and truth. Thus, Canova’s restrained tenderness contrasts with the passionate turmoil of Baroque art. Love here is not sensual conquest but spiritual restoration.

6. Reception and Legacy

When first exhibited in Rome, Psyche Revived by Cupid’s Kiss was immediately recognized as a masterpiece. Critics called it “the triumph of grace over passion.” Visitors were captivated by its lifelike delicacy and emotional power conveyed without exaggeration.

It became a defining work of Neoclassicism, illustrating how calm form could evoke profound feeling. The sculpture influenced generations of artists — including Bertel Thorvaldsen, Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux, and later Romantic painters who explored the harmony of body and spirit.

Even into the 19th century, it remained a reference point for art academies, where students studied its anatomy, symmetry, and emotion as an ideal of beauty.

7. Observing the Sculpture in the Louvre

The sculpture is displayed in the Denon Wing, Room 403, near Michelangelo’s Dying Slave and Rebellious Slave. The museum’s lighting enhances the subtle contrast between shadow and shine that Canova intended.

For a student observer:

- Move around the sculpture; every angle reveals a new emotional dialogue.

- Notice how light travels across the marble — the figures almost seem to breathe.

- Observe how Cupid’s downward gaze meets Psyche’s upward movement, forming an eternal loop of love and revival.

- Pay attention to the texture contrast between the finely polished skin and the rough rock — symbolizing transformation from mortality to divinity.

This active observation turns the experience from passive viewing into an encounter with Canova’s philosophy of life and art.

8. Enduring Meaning for Students

For modern students, Psyche Revived by Cupid’s Kiss offers three timeless lessons:

- Technical mastery serves emotional truth. Canova’s polish and proportion allow the emotion to flow through form rather than overwhelm it.

- Balance creates beauty. The sculpture’s X-shaped harmony shows how composition guides feeling.

- Love awakens the soul. Beyond its mythic story, it reminds us that true beauty unites body and spirit, art and life.

In this sense, Canova’s work is not just about marble or myth — it is about humanity’s eternal desire for renewal, compassion, and transcendence.

Conclusion

In Psyche Revived by Cupid’s Kiss, Antonio Canova transformed stone into spirit. He captured the silent instant where death yields to love, and stillness becomes motion. His art bridges mythology and philosophy, sensuality and serenity, mortal and divine.

For all who stand before it — whether in wonder, study, or reverence — the message remains the same: Love revives, beauty endures, and art can awaken the sleeping soul.

“The beauty of the body is the beauty of the soul made visible.”

— Antonio Canova

You must be logged in to post a comment.