January 5, 1933 — Steel, Strain, and the Day the Golden Gate Became Measurable

A collaboration between Lewis McLain & AI

January 5, 1933 was the day the Golden Gate Bridge stopped being an argument and became a set of numbers, tolerances, stresses, and human limits. It was the day the bridge entered the physical world—where ideas are tested not by opinion, but by wind, gravity, and steel stretched to its breaking point.

This is what made that decision extraordinary: nothing at this scale had ever been built under conditions like these.

Before January 5: a problem defined by physics

The Golden Gate strait is not merely wide; it is hostile. The main span would need to cross 4,200 feet of open water—longer than any suspension bridge span in the world at the time. The water below reached depths of over 300 feet, with tidal currents exceeding 7 knots. Winds routinely pushed 50–60 mph through the narrow opening. Add fog, salt corrosion, and an active earthquake zone, and the engineering margins grew thin fast.

Critics were not being timid. They were doing the math.

The decision to build anyway

The project moved forward under the leadership of Joseph Strauss, supported by local governments and financed—barely—when Amadeo Giannini personally backed the bonds. The theoretical backbone of the structure came from calculations performed largely by Charles Alton Ellis, whose work translated vision into equations that said, yes, this can stand.

On January 5, those equations met the bay.

Foundations: anchoring the impossible

The first technical challenge was not the span—it was the towers.

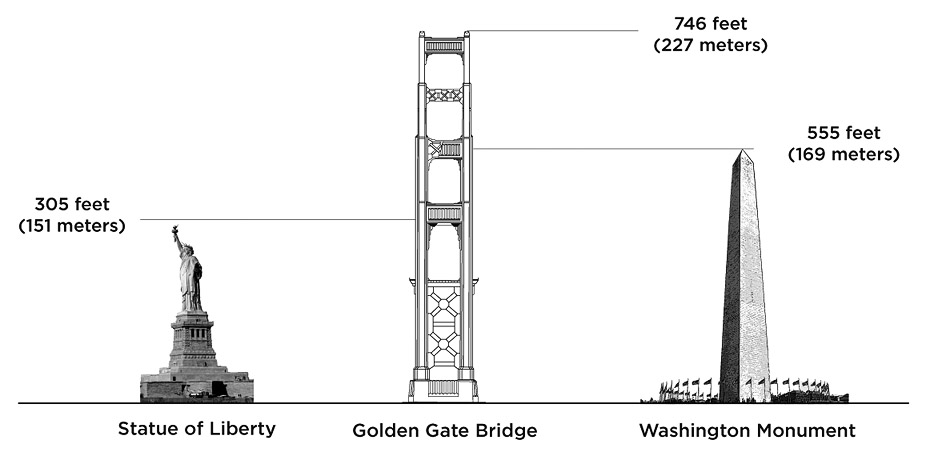

Each tower would rise 746 feet above the water, taller than most buildings of the era. To support them, crews sank massive foundations into bedrock far below the surface. This required working from floating platforms, battling currents that could push equipment sideways and make precise placement nearly impossible.

The south tower’s foundation alone weighed over 60,000 tons once complete.

Towers first, cables later

Construction followed a strict sequence:

- Foundations and piers

- Steel towers

- Main suspension cables

- Vertical suspender ropes

- Roadway deck

The towers were built section by section, steel plates riveted together in midair. Workers balanced on beams sometimes no wider than a boot sole, aligning steel to tolerances measured in fractions of an inch—because errors multiplied dramatically across a mile-long span.

The cables: strength measured in thousands of miles

The bridge’s two main cables remain its most astonishing technical feat.

Each cable:

- Measures 36⅜ inches in diameter

- Contains 27,572 individual steel wires

- Each wire is 0.192 inches thick

- Total wire length per cable: ~80,000 miles

- Combined wire length: enough to wrap around the Earth more than three times

The wires were not prefabricated. They were spun in place using a moving wheel that carried each wire back and forth across the span, one at a time. Cable spinning took six months, with workers exposed to wind, fog, and vertigo at all hours.

Each cable supports a load of roughly 25,000 tons.

Tension, strain, and living steel

Steel under tension behaves differently than steel at rest. Engineers calculated:

- Dead load (weight of the bridge itself)

- Live load (traffic, pedestrians, wind)

- Dynamic wind loading

- Seismic forces

At full load, the bridge can sway up to 27 feet laterally. This is not a flaw. It is survival. Rigidity would have meant failure.

The bridge is designed to move, not resist movement.

Safety engineered into the process

Strauss insisted on safety innovations unheard of at the time:

- Mandatory hard hats

- Lifelines and handrails

- On-site medical staff

- And the massive safety net beneath the deck

The net saved 19 men—the “Halfway-to-Hell Club.” Eleven still died, ten in a single accident when a scaffold tore through the net. Even so, the fatality rate was far lower than comparable projects of the era.

Safety, for once, was treated as a technical requirement—not an afterthought.

The roadway: hanging a city street in the air

The deck was assembled in prefabricated sections and lifted into place by cranes mounted on the cables themselves. Once attached, vertical suspender ropes transferred load from deck to cable, distributing weight evenly.

Final dimensions:

- Total length: 8,981 feet

- Main span: 4,200 feet

- Width: 90 feet

- Clearance above water: 220 feet

Every number mattered. Change one, and the system changed everywhere.

After January 5: proof through survival

When the bridge opened in 1937, it immediately carried traffic loads no one fully anticipated. It later survived:

- The 1957 Fort Point earthquake

- The 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake

- Constant wind cycles for nearly a century

Its survival validated not only the structure, but the philosophy behind it: design for movement, design for uncertainty, design for people.

What January 5 ultimately celebrates

January 5 is not a date about ribbon-cutting. It is about committing to numbers you cannot yet test and trusting human skill to meet them.

It honors the moment when:

- theory met tide,

- equations met wind,

- safety met necessity,

- and steel was asked to behave like a living thing.

The Golden Gate Bridge did not begin as poetry.

It began as calculations, rivets, wire under strain, and men willing to trust both.

That trust—measured in miles, tons, inches, and lives—is what January 5 truly marks.

You must be logged in to post a comment.