I have no Muslim neighbors or friends as far as I know. My best friends, Steve & Beverly Witt (strong Christians) in Houston, have Sunni Muslim clients who became close friends. My envy rose as I talked to Steve about the enlightening conversations they had with their friends, Omar & Sahar, now considered family.

The friends have pointed out how they have confronted other Muslims who make statements about the Quran without actual knowledge, as if they have not read the Quran.

This was a fascinating revelation to me, as I was simply dumb about the subject until I talked to Steve.

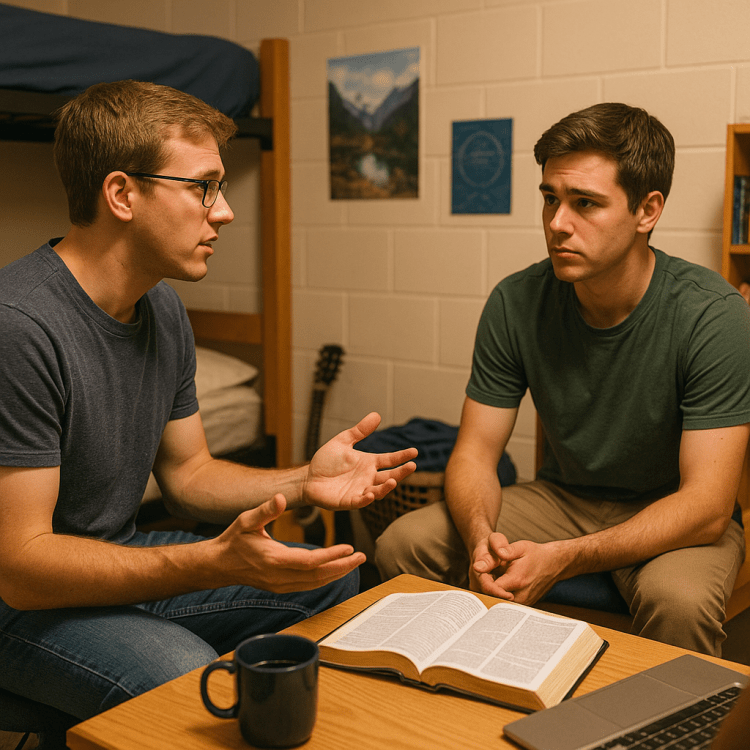

Then Steve introduced me to another story of Nabeel Qureshi in his book and video. I then bought and introduced the story to our couples Bible Study group a couple of years ago.

“Seeking Allah, Finding Jesus” is the autobiographical account of Nabeel Qureshi, a devout Pakistani-American Muslim who converted to Christianity after an intense journey of theological, spiritual, and personal exploration. The book presents his internal conflict as he wrestled with his love and loyalty to his Muslim upbringing and his deepening conviction that Jesus is who he claimed to be—the Son of God.

Nabeel was raised in a loving and devout Ahmadi Muslim family that valued honor, tradition, and rigorous study of the Qur’an and Hadith. His early years were filled with pride in Islamic values and an affectionate home. As a college student, Nabeel formed a close friendship with a Christian peer, David Wood, which became the foundation for in-depth interfaith dialogues.

Their long discussions led Nabeel to compare the Bible and the Qur’an, explore the life of Jesus versus that of Muhammad, and critically evaluate both worldviews.

Central to Nabeel’s journey were questions about the historical reliability of Christian scripture, the nature of God, and the person of Jesus. He studied early Christian writings, explored the doctrine of the Trinity, and examined claims of Jesus’ death and resurrection. At the same time, he critically studied Islamic history, leading him to question the Hadith, the life of Muhammad, and the foundations of his inherited beliefs.

Eventually, a series of dreams, which he interprets as divine signs, and the overwhelming sense of God’s love led Nabeel to embrace Christianity. His conversion came at great personal cost—grieving his family and community—yet he ultimately found peace in his faith in Jesus.

“Seeking Allah, Finding Jesus” is not just a critique of Islam or a defense of Christianity; it is a heartfelt narrative of identity, truth-seeking, and the cost of discipleship. Qureshi presents both faiths respectfully and invites readers into his emotional and intellectual transformation.

This memoir has resonated with readers for its honest portrayal of interfaith dialogue, deep scholarship, and spiritual conviction. It also serves as a bridge of understanding between Muslims and Christians, fostering empathy and curiosity. Sadly, Qureshi died from stomach cancer at the age of 34. He died while at MD Anderson Hospital in Houston.

This paper is my effort to direct AI to help me (and you) to understand more about exactly what the Quran says and to point out connections to the Bible you may find new information, as I did.

My self-study boosted my beliefs as a Christian while elevating my respect for peaceful Muslims. LFM

For many people unfamiliar with Islam, questions about the religion’s views on Jesus, the treatment of non-Muslims, and the causes behind violent extremism are often clouded by confusion or misinformation. This essay seeks to provide a clear and complete introduction to these topics, focusing especially on how Muslims view Jesus, the role of Hadith, the differences between Sunni and Shia Islam, and the theological and historical approach toward people of other faiths, particularly Christians. We will also confront the troubling reality of terrorist acts committed in the name of Islam, and how the broader Muslim world has responded.

Jesus in Islam: A Revered Prophet, Not Divine

In the Qur’an, Jesus (ʿĪsā in Arabic) is deeply honored as one of the greatest prophets. Muslims believe in his virgin birth to Mary (Maryam), his ability to perform miracles, and his role as the Messiah. However, Islam rejects the idea of his divinity or his crucifixion. According to the Qur’an, Jesus was not killed or crucified, but rather it appeared so to people, and God raised him to Himself (Surah 4:157–158). Jesus is called a “Word from God” and a “spirit from Him” (Surah 4:171), titles that reflect his special status without equating him with divinity.

One often overlooked aspect is the Qur’anic reference to the Holy Spirit (Rūḥ al-Qudus), mentioned multiple times in relation to Jesus. For example, Surah 2:87 says, “We gave Jesus, the son of Mary, clear signs and strengthened him with the Holy Spirit.” Similarly, Surah 5:110 states, “…and when I [God] strengthened you [Jesus] with the Holy Spirit…” These verses indicate divine support and inspiration granted to Jesus, and while Islamic scholars typically interpret the Holy Spirit as the angel Gabriel, the concept parallels Christian understandings of spiritual empowerment.

Unlike Christianity, Islam teaches that Jesus was not the Son of God, and that worship should be directed to God (Allah) alone. Nevertheless, Muslims expect Jesus to return before the Day of Judgment to restore justice and defeat the false messiah (al-Dajjal). Mary is also greatly revered, with an entire chapter in the Qur’an (Surah Maryam) named after her.

Understanding Hadith and Sahih Hadith

The Hadith literature records the sayings, actions, and approvals of the Prophet Muhammad and serves as a vital source for Islamic law and ethics, second only to the Qur’an. A Hadith consists of two parts: the isnād (chain of narrators) and the matn (text of the narration). Hadiths are classified based on their reliability. The highest grade is Sahih, meaning “authentic.” A Sahih Hadith must meet strict criteria: a continuous and unbroken chain of trustworthy narrators with strong memory, free of contradictions and hidden defects. Famous Sahih collections include Sahih al-Bukhari and Sahih Muslim.

Other Hadith classifications include: • Hasan (good): Slightly weaker memory, but still acceptable • Da’if (weak): Unreliable narrators or broken chains • Mawdu‘ (fabricated): Forged and entirely rejected

Both Sunni and Shia Muslims rely on Hadith, though they often refer to different collections and prefer narrators aligned with their historical perspectives.

Sunni and Shia Islam: A Historic Divide

The split between Sunni and Shia Islam originated as a political dispute over who should lead the Muslim community after the Prophet Muhammad’s death. Sunnis believe the leader (Caliph) should be chosen by consensus and merit. Shias, however, believe leadership (Imamate) must remain within the Prophet’s family, beginning with his cousin and son-in-law Ali ibn Abi Talib. An Imam in Shia Islam is not just a prayer leader, but a divinely guided spiritual and temporal authority.

Over time, this political split evolved into theological and legal differences:

• Sunnis make up about 85–90% of Muslims worldwide and follow one of four major legal schools (Hanafi, Shafi‘i, Maliki, Hanbali).

• Shias, particularly the Twelvers (dominant in Iran and Iraq), believe in a line of 12 divinely guided Imams. The twelfth Imam, known as al-Mahdi, is believed to be in occultation and will return as a messianic figure.

• Shias often emphasize themes of martyrdom and justice, especially in commemorating Husayn’s death at Karbala in 680 CE, which is central to Shia identity.

Despite their differences, both groups share the core tenets of Islam: belief in one God, the Qur’an, the Prophet Muhammad, prayer, fasting, charity, and pilgrimage.

Treatment of Non-Muslims: Coexistence and Compassion

Islam distinguishes between various groups of non-Muslims. Christians and Jews are referred to as “People of the Book” (Ahl al-Kitab) and are afforded special status. The Qur’an praises many of them for righteousness and affirms their scriptures as having originally come from God (though Muslims believe the original texts have been altered over time).

Historically, Muslims and Christians coexisted in many empires, including: • The Ottoman Empire (Sunni) where Christians had autonomy under the “dhimmi” system • Safavid Persia (Shia) where Christian minorities like Armenians lived in protected communities

In modern Israel, Muslims, Christians, and Jews coexist under a shared civic structure. Approximately 21% of Israel’s population is Muslim, with full citizenship rights, voting power, and religious freedom, despite ongoing political tensions in the region.

Islam teaches that peaceful coexistence is a divine mandate: “God does not forbid you from being kind and just toward those who do not fight you because of religion” (Qur’an 60:8)

However, when groups show aggression or threaten the Muslim community, Islam allows for defensive warfare, never offensive conquest for faith. Even in wartime, the Qur’an forbids harming non-combatants and destroying places of worship.

Who Are the Kāfirs (“Infidels”)?

The term “infidel” is not a direct Islamic concept. The Qur’anic term kāfir means someone who “rejects or conceals the truth,” and is context-dependent. While the Qur’an criticizes those who reject God after the truth has been made clear, it never gives ordinary Muslims the license to harm others based on belief alone.

Extremist groups, however, misuse this term to justify violence against Muslims and non-Muslims alike. This practice, called takfīr (declaring someone a disbeliever), is condemned by mainstream Sunni and Shia scholars alike.

What About 9/11 and Other Attacks?

The terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, were carried out by 19 extremists associated with al-Qaeda, led by Osama bin Laden. They claimed to act in the name of Islam, but their ideology was widely and immediately condemned by the Muslim world:

• Egypt’s Al-Azhar University (Sunni) denounced the attacks • Iraq’s Ayatollah Sistani (Shia) labeled terrorism un-Islamic

• Numerous fatwas (legal rulings) declared that killing innocent civilians violates Islamic law

Islam forbids both suicide and the killing of innocents. The Qur’an states: “Whoever kills a soul… it is as if he has slain all of mankind” (Qur’an 5:32)

Unfortunately, political grievances, propaganda, and misinterpretations have been used to radicalize individuals. Yet these ideologies do not reflect the beliefs of the 1.9 billion Muslims worldwide, most of whom denounce extremism and violence.

Conclusion: A Faith of Peace, Diversity, and Shared Values

Islam, like Christianity and Judaism, is a complex and internally diverse faith. It reveres Jesus and Mary, values justice and mercy, and includes centuries of peaceful coexistence with other faiths. While divisions between Sunnis and Shias remain, both traditions denounce extremist violence and affirm the rights and dignity of non-Muslims. Acts of terror, such as 9/11, are political crimes cloaked in religious language and are universally condemned by mainstream Muslims.

For those unfamiliar with Islam, learning about its true teachings on Jesus, Hadith, and the treatment of others is a necessary step toward mutual understanding. As with all world religions, Islam must be judged by its core texts, mainstream beliefs, and the lives of the vast majority of its followers—not the actions of a violent few. LFM

www.ClearQuran.com for a complete English translation of the Quran you can download. Below is a brief summary of each of the 114 chapters of the Quran along with an AI analysis of the agreements and difference when compared to the Bible.

1. Al-Fatiha (The Opening):

This foundational surah is a heartfelt prayer for guidance, mercy, and steadfastness. It emphasizes God’s role as Lord of all worlds, His mercy, and the believer’s dependence on Him. As the essence of the Qur’an, it is recited in every unit of Muslim prayer and captures the relationship between Creator and servant.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Both faiths uphold God’s mercy, guidance, and lordship. Similar themes appear in the Lord’s Prayer (Matthew 6:9–13).

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: The Bible refers to God as “Father,” a concept absent here. No mention of Jesus, grace, or redemption.

2. Al-Baqarah (The Cow):

The longest chapter of the Qur’an, it introduces legal, spiritual, and ethical guidance. Topics include belief, prayer, charity, fasting, pilgrimage, marriage, financial conduct, and justice. It revisits the stories of past prophets and establishes the foundational law for Muslim society.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Many laws echo Mosaic commandments (Exodus, Leviticus). The roles of Adam, Abraham, and Moses are shared.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: It denies original sin and Jesus’ divinity, and introduces doctrines (e.g., abrogation, 2:106) foreign to biblical theology.

3. Al-Imran (The Family of Imran):

Focused on divine guidance and the relationship with earlier Abrahamic faiths, this surah addresses theological debates, the stories of Mary and Jesus, and early Muslim experiences like the Battle of Uhud. It encourages faith, patience, and trust in God’s wisdom.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Affirms the virgin birth of Jesus (3:45–47) and honors Mary, consistent with Luke 1.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: Denies Jesus’ divinity and crucifixion. The “Gospel” is viewed as a book revealed to Jesus, not about him.

4. An-Nisa (The Women):

This surah offers detailed laws regarding family, inheritance, and the rights of women and orphans. It also covers warfare ethics, social justice, and the consequences of hypocrisy. Its name reflects the central role of women’s status and protection.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Protecting widows and orphans (James 1:27) and stressing justice parallels biblical values.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: Allows polygamy (4:3), denies the Trinity (4:171), and rejects the crucifixion of Jesus (4:157).

5. Al-Ma’idah (The Table Spread):

Addressing covenants, lawfulness, and interfaith relations, this surah discusses dietary regulations, punishments, and leadership. It reflects on the messages of Moses and Jesus and the importance of upholding divine law.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Upholds moral law, accountability, and God’s covenant—found in both Testaments. Mentions the Last Supper-like imagery (5:112–115).

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: Denies the Trinity and Jesus’ divinity (5:72–75), and criticizes Christian theology directly.

6. Al-An’am (The Cattle):

A strong call to monotheism, this chapter critiques idolatry and emphasizes divine signs in nature. It retells the stories of earlier prophets and stresses the moral responsibility of individuals and the importance of revelation.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Monotheism, rejection of idols, and affirming God as Creator mirrors the Ten Commandments.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: Rejects Jesus as divine and redeemer. Denies inherited sin and redemptive grace.

7. Al-A’raf (The Heights):

Named after a symbolic barrier between Heaven and Hell, this surah recounts stories of past nations who denied their prophets. It emphasizes the consequences of pride and disobedience, and the importance of repentance.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Biblical narratives like Adam, Noah, Moses, and Pharaoh are reaffirmed. Call to repentance is consistent.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: Challenges Jewish authority and Christian doctrine. No acknowledgment of Jesus’ salvific role.

8. Al-Anfal (The Spoils of War):

Revealed after the Battle of Badr, this chapter discusses the distribution of war gains, ethics in warfare, and divine assistance. It highlights discipline, unity, and spiritual readiness.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: The Old Testament also contains laws on warfare and God assisting Israel in battle (e.g., Joshua).

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: New Testament teachings shift toward peace and enemy love (Matthew 5:44), unlike the permission to fight in this surah.

9. At-Tawbah (The Repentance):

The only surah without “Bismillah,” it outlines consequences for treaty violations and warns against hypocrisy. It stresses the need for sincere repentance, sacrifice, and loyalty to the Muslim community.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Repentance and justice are central themes in both Testaments. Hypocrisy is condemned (Matthew 23).

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: Contains harsh war verses (e.g., 9:5) that differ from the New Testament’s call to love enemies and seek peace.

10. Yunus (Jonah):

Emphasizing God’s mercy and the truth of revelation, this surah calls people to faith through reflection and warns of consequences for rejecting the truth. The story of Jonah illustrates a community that repented and was saved.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: The story of Jonah and Nineveh’s repentance (Book of Jonah) matches well. God’s mercy is a shared theme.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: No connection made between Jonah and Jesus as in Matthew 12:40. The Qur’an also lacks the narrative of atonement or personal relationship with God through Christ.

11. Hud:

This surah tells the stories of several prophets—Noah, Hud, Salih, Abraham, Lot, Shu‘ayb, and Moses—emphasizing their persistence in delivering God’s message. It stresses that consequences come when communities persist in wrongdoing despite repeated warnings.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: These prophetic figures and their roles are shared in both the Bible and Qur’an. Messages of repentance and divine warning match themes found in Genesis, Exodus, and the prophetic books.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: While the Qur’an shows continuity of prophetic mission, it lacks the covenantal narrative of Israel as chosen people. The surah omits any reference to Jesus or salvation history as fulfilled in the New Testament.

12. Yusuf (Joseph):

A beautifully told narrative focused entirely on the life of Prophet Joseph. It addresses themes of jealousy, patience, loyalty, and forgiveness. Unlike other surahs, it provides a continuous story arc with emotional and spiritual lessons.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Closely parallels Genesis 37–50. Themes of betrayal, patience, dream interpretation, and reconciliation are remarkably aligned.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: The Qur’an emphasizes Joseph’s status as a prophet and teacher of monotheism more explicitly. No mention of God’s covenant with Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob that frames Joseph’s biblical role.

13. Ar-Ra’d (The Thunder):

This surah juxtaposes God’s creative power with human disbelief. It explores the nature of divine will, signs in creation, and the reality of resurrection. Thunder is presented as a symbol of God’s majesty and authority.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Nature as evidence of God’s power (Psalm 19, Romans 1:20) and the idea of resurrection (Daniel 12:2) are shared themes.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: While resurrection is shared, the Qur’anic concept emphasizes judgment without a redemptive intermediary. No reference to Christ’s resurrection as the basis for hope (1 Corinthians 15).

14. Ibrahim (Abraham):

Centered on the mission of Prophet Abraham, this chapter emphasizes gratitude, monotheism, and prayer for future generations. It also contrasts the fate of the grateful versus the arrogant and ungrateful.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Abraham’s faith, prayerfulness, and covenantal obedience are affirmed (Genesis 12–22, Romans 4).

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: No mention of Isaac’s near-sacrifice; Qur’an implies it was Ishmael (though not named here). Also, Abraham is portrayed as a prophet of Islam rather than as part of a messianic lineage.

15. Al-Hijr (The Rocky Tract):

A warning to disbelievers, this surah recounts the destruction of past civilizations such as the people of Thamud. It reassures believers of God’s protection and the Qur’an’s preservation.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: God’s destruction of rebellious nations parallels Sodom, Gomorrah, and others in Genesis and the Prophets.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: There is a Qur’anic claim of the perfect preservation of its scripture (15:9), contrasting with Christian belief that the Bible, though divinely inspired, was compiled through human history.

16. An-Nahl (The Bee):

A reflection on God’s blessings, this surah covers themes of creation, guidance, gratitude, and the consequences of denial. The bee is highlighted as a symbol of divine design.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Creation reflects God’s wisdom and care (Job 12:7–10, Romans 1:20). Gratitude and obedience are universal scriptural values.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: Salvation in Christianity centers on faith in Christ, not merely gratitude and submission. The surah omits any discussion of sin, atonement, or divine sonship.

17. Al-Isra (The Night Journey):

Named after the Prophet’s miraculous night journey and ascension, it includes moral and legal teachings. It stresses personal accountability, the importance of the Qur’an, and honoring parents.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Honor your father and mother (Exodus 20:12) and moral accountability are shared. Miraculous ascensions (e.g., Elijah, 2 Kings 2) also have precedent.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: The surah refers to Muhammad’s night journey as central spiritual proof, which is not recognized in biblical theology. No mention of Jesus’ role in spiritual ascent or mediation.

18. Al-Kahf (The Cave):

Contains stories of the People of the Cave, Moses and Khidr, and Dhul-Qarnayn. It focuses on trials of faith, knowledge, wealth, and power, and is traditionally recited on Fridays for spiritual protection.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Themes of endurance, divine testing, and wisdom echo the book of Job, Proverbs, and parables of Jesus.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: The stories of the Sleepers of the Cave and Dhul-Qarnayn do not appear in the Bible. Moses’ meeting with Khidr has no biblical counterpart.

19. Maryam (Mary):

Focuses on the birth of Jesus and recounts the stories of other prophets. It emphasizes mercy, God’s power over life and death, and the honor of Mary, one of the most revered women in Islam.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Affirms the virgin birth (Luke 1), Mary’s purity, and Jesus’ miraculous arrival.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: Denies Jesus as Son of God or Savior (19:35). Jesus speaks from the cradle, a narrative not found in the Bible.

20. Ta-Ha:

This chapter recounts the mission of Moses and Pharaoh’s defiance. It blends personal spiritual lessons with reminders of divine mercy and the power of revelation to transform hearts.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Moses’ mission, the burning bush, and Pharaoh’s resistance match closely with Exodus.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: The Qur’an focuses on Moses as a forerunner to Muhammad’s message. There is no mention of Passover, covenant, or messianic foreshadowing through Moses’ role.

21. Al-Anbiya (The Prophets):

This surah recounts the trials of various prophets—Abraham, Lot, Moses, Aaron, David, Solomon, and others—and emphasizes the consistent message of monotheism. It shows God’s support for the faithful and warns against arrogance.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Many of these prophets and their struggles are shared in the Old Testament. Monotheism and divine justice align with biblical teachings.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: Prophets are seen in the Qur’an as forerunners of Islam rather than precursors to Christ. Jesus is included as a prophet but not the Messiah in the New Testament sense.

22. Al-Hajj (The Pilgrimage):

Named after the major pilgrimage to Mecca, this surah discusses rituals, resurrection, divine judgment, and the need for sincerity in worship. It reflects both spiritual and societal dimensions of religion.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Pilgrimage (Exodus 23:14–17) and worship festivals are also biblical. Judgment and resurrection are shared themes.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: The Hajj is a uniquely Islamic ritual, not found in the Bible. The Christian path emphasizes a personal relationship with God through Christ, not ritual pilgrimage.

23. Al-Mu’minun (The Believers):

This chapter lists the qualities of true believers—humility in prayer, charity, chastity, and trustworthiness—and contrasts them with those who deny the truth. It highlights the spiritual rewards for the faithful.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: The fruits of the Spirit (Galatians 5:22–23) and teachings of Jesus about humility and righteousness parallel these traits.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: While good character is valued in both faiths, Christianity teaches salvation is by grace through faith—not merit-based virtues alone (Ephesians 2:8–9).

24. An-Nur (The Light):

With its emphasis on morality and modesty, this surah addresses slander, social conduct, and the proper behavior between men and women. It includes the famous “Light Verse” symbolizing divine guidance.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Modesty, sexual morality, and social integrity are found throughout the Bible (1 Timothy 2:9, Proverbs 6).

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: The Qur’an prescribes legal punishments for slander and adultery. The New Testament promotes forgiveness and repentance instead of corporal justice (John 8:1–11).

25. Al-Furqan (The Criterion):

This surah establishes the Qur’an as a divine criterion between truth and falsehood. It describes the characteristics of disbelievers and concludes with a portrait of the “servants of the Most Merciful” who exemplify humility, patience, and devotion.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: The idea of discerning truth and living with humility and compassion echoes Psalms and the teachings of Jesus.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: The Qur’an is positioned as the final and corrected scripture, whereas the Bible presents itself as the complete Word of God (2 Timothy 3:16–17, Revelation 22:18–19).

26. Ash-Shu’ara (The Poets):

Featuring the repeated struggles of past prophets, this surah highlights the importance of revelation and warns against poetic manipulation and falsehood. It underscores the pattern of prophetic rejection.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: The rejection of prophets and the persistence of God’s messengers are consistent themes (e.g., Jeremiah, Elijah).

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: The surah critiques human poetry and emotional influence, while biblical texts include prophetic poetry and psalms inspired by the Holy Spirit.

27. An-Naml (The Ant):

Named after the story of Solomon and the ants, it showcases the wisdom of prophets and divine signs in nature. Stories of Moses, Solomon, and others emphasize the victory of truth.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Solomon’s wisdom, Moses’ mission, and signs of creation reflect themes found in 1 Kings and Exodus.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: The detailed story of Solomon communicating with animals and the Queen of Sheba’s visit differs significantly in tone and content from 1 Kings 10.

28. Al-Qasas (The Stories):

Focused on the life of Moses, this surah details his early years, mission, and encounters with Pharaoh. It also touches on Qarun’s arrogance and reminds believers that God guides whom He wills.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: The life of Moses aligns closely with Exodus. Themes of deliverance, injustice, and God’s calling are shared.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: The Qur’an does not contain the same narrative of the burning bush as symbolic of God’s holiness or the Passover. Jesus is absent from typology.

29. Al-Ankabut (The Spider):

Named after the fragile spider web, it uses metaphors to illustrate the futility of placing trust in anything besides God. It addresses trials faced by believers and calls for sincere faith.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Metaphors of frailty (e.g., Psalms 39:5) and calls to persevere in trials (James 1:2–4) align well.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: The focus remains on works and trial endurance rather than redemption through grace or assurance through Christ.

30. Ar-Rum (The Romans):

This surah opens with the prediction of a Roman victory and uses it to highlight divine control over history. It emphasizes signs in creation and human relationships as evidence of God’s power.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Prophecy, God’s control of empires (Daniel 2), and natural signs affirm God’s rule are shared concepts.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: The Qur’an’s reference to the Romans serves Islamic prophecy and worldview; there is no reference to Christ’s redemptive work through Rome (e.g., crucifixion) as central to Christian theology

31. Luqman:

This chapter is named after a wise man who counsels his son. It contains moral and spiritual advice, warnings against arrogance and idolatry, and encouragement to show gratitude, humility, and respect toward one’s parents and the truth.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Similar wisdom teachings appear in Proverbs and Ecclesiastes. Honoring parents and rejecting idolatry are emphasized in Exodus 20:12 and Deuteronomy 6.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: Biblical wisdom literature often points toward fear of the Lord as tied to covenant and messianic hope. Luqman is not a biblical figure, and there is no reference to Jesus or redemptive grace.

32. As-Sajdah (The Prostration):

A spiritually reflective chapter that emphasizes the importance of divine revelation, the eventuality of resurrection, and the distinction between those who believe and those who reject faith.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: The resurrection of the dead, judgment, and distinction between righteous and wicked are consistent with Daniel 12 and John 5:28–29.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: The Qur’an teaches bodily resurrection without referencing Christ’s resurrection as its foundation. The gospel’s central claim—that Jesus rose to defeat death—is not acknowledged.

33. Al-Ahzab (The Confederates):

Focuses on the Battle of the Trench and broader issues of social structure, marriage, hijab, and loyalty to the Prophet. It clarifies the unique status of Muhammad and urges strong moral conduct.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Encouragement of modesty, moral conduct, and communal integrity can be found in texts like 1 Timothy 2:9–10 and 1 Peter 3.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: The exalted status of Muhammad as a moral model is central; Christianity instead centers moral emulation on Christ (Philippians 2). The surah’s handling of marriage laws diverges from biblical ethics.

34. Saba (Sheba):

Named after the ancient kingdom of Sheba, this chapter contrasts the fates of grateful and ungrateful societies. It highlights God’s gifts to David and Solomon and affirms resurrection.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: The stories of David and Solomon and the Queen of Sheba (1 Kings 10) are affirmed. Gratitude and divine wisdom are shared themes.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: The Qur’an presents Solomon as a prophet with command over the wind and jinn, differing from his portrayal as a king of Israel. The centrality of messianic lineage is missing.

35. Fatir (The Originator):

This surah extols God’s role as the originator of creation. It discusses the angels, signs of divine power, and warns of the consequences of disbelief and ingratitude.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: God as Creator (Genesis 1), provider of angels (Hebrews 1:14), and giver of life is affirmed throughout Scripture.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: The surah does not reference Christ as the agent of creation (John 1:1–3) or redemption. The New Testament links creation and salvation together in Jesus.

36. Ya-Sin:

Known as the “heart of the Qur’an,” it urges reflection on divine signs, resurrection, and revelation. Through parables and warnings, it addresses both sincerity and stubborn denial.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: The importance of sincere faith, final judgment, and responding to God’s message are all shared themes (Matthew 13, Romans 2).

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: The Qur’an emphasizes Muhammad as the Warner, while the Bible presents Christ as Savior and Redeemer, not only a messenger.

37. As-Saffat (Those Who Set the Ranks):

A chapter filled with stories of past prophets and affirmations of monotheism. It defends the belief in resurrection and criticizes false gods.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Stories of Noah, Abraham, and Moses align with Genesis and Exodus. The rejection of idolatry is a shared value.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: Abraham’s near-sacrifice is believed to be of Ishmael, not Isaac. Jesus’ central role in resurrection is absent.

38. Sad:

Addresses the resistance of disbelievers to the Prophet’s message. It narrates stories of David, Solomon, and Job, focusing on justice, patience, and accountability.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: David’s and Job’s trials and virtues are also emphasized in 1 Samuel, Psalms, and Job. Themes of repentance and divine mercy are shared.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: Jesus is not seen as David’s heir or fulfillment of messianic prophecy. The Qur’an’s David is a prophet, not the father of the Messiah.

39. Az-Zumar (The Groups):

A powerful meditation on sincere worship, divine justice, and the contrast between those who submit to God and those who follow falsehood.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Sincerity in worship, fear of judgment, and ultimate accountability before God are affirmed throughout both Testaments.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: Salvation by grace through Christ (Ephesians 2:8) is absent. Righteousness in the Qur’an depends on submission and deeds.

40. Ghafir (The Forgiver):

Highlights God’s mercy and willingness to forgive. It contains the story of a believing man from Pharaoh’s household and themes of warning, patience, and divine victory.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: God’s mercy, patience, and justice echo biblical messages (Exodus 34:6–7, Psalm 103).

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: Forgiveness in the Qur’an is conditional on repentance and deeds. The Bible teaches forgiveness through Christ’s atoning sacrifice.

41. Fussilat (Explained in Detail):

This surah emphasizes the clarity and divine origin of the Qur’an, urging reflection on creation as proof of God’s existence. It recounts the fate of those who rejected past prophets and reinforces the certainty of resurrection.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: The call to reflect on creation as evidence of God’s power (Romans 1:20, Psalm 19:1) and prophetic warnings are consistent with biblical texts.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: The Qur’an is described as the final clear scripture, while the Bible claims completeness and finality in Christ (Hebrews 1:1–2). Jesus is absent as the culmination of revelation.

42. Ash-Shura (Consultation):

The surah takes its name from the principle of mutual consultation. It stresses the unity of divine revelation, the mercy of God, and the importance of cooperation and shared decision-making in community life.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: The Bible encourages unity, humility, and shared leadership (Acts 15, Proverbs 15:22). God’s mercy is a shared divine trait.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: The Prophet Muhammad is viewed as the final messenger, a claim not accepted in Christianity. There is no mention of the Holy Spirit’s indwelling role in Christian decision-making (John 14:26).

43. Az-Zukhruf (Ornaments of Gold):

It critiques materialism and pride, especially among the Meccans, and addresses common objections to monotheism. It highlights the flawed logic of idol worship and reaffirms the message of earlier prophets.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Warnings against pride and greed (Luke 12:15, Proverbs 16:18) and affirmations of monotheism are echoed in both Testaments.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: The surah critiques the belief in Jesus’ divinity (43:81–82), which is central to Christian theology (John 1:1, Colossians 2:9).

44. Ad-Dukhan (The Smoke):

This surah warns of a coming day of judgment marked by a cloud of smoke. It references the destruction of past peoples like Pharaoh’s followers and calls for people to heed the Qur’anic message.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Day of judgment, destruction of Pharaoh, and divine warnings are shared concepts (Exodus 7–12, Revelation 8–9).

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: The biblical message points toward redemption through judgment in Christ (Revelation 7:14), while this surah offers no mediator.

45. Al-Jathiyah (The Crouching):

The chapter speaks of divine signs in the natural world and history. It describes how all communities will be judged as they crouch before God on the Day of Judgment.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: The theme of every knee bowing before God (Isaiah 45:23, Romans 14:11) and divine judgment matches biblical prophecy.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: The Qur’an rejects Jesus’ role in judgment and mediation, while in Christianity, Jesus is the appointed judge (Acts 17:31, John 5:22).

46. Al-Ahqaf (The Wind-Curved Sandhills):

Named after the region inhabited by the people of ‘Ad, this surah recounts their downfall and highlights the consistency of prophetic messages. It reinforces personal responsibility and the reality of resurrection.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: The fall of proud civilizations due to their rejection of God is echoed in Isaiah, Jeremiah, and the book of Daniel.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: Prophetic messages are said to lead to Islam, whereas the Bible sees prophecy as culminating in Jesus Christ (Luke 24:27, Hebrews 1:1–2).

47. Muhammad:

Named after the Prophet, this surah discusses the distinction between believers and disbelievers, the importance of fighting in the cause of justice, and the reward awaiting the faithful.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: God will ultimately separate the faithful from the wicked (Matthew 25:31–46). Justice and endurance are praised.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: Fighting for religious cause is not part of the New Testament ethic. Jesus taught self-sacrifice and enemy love (Matthew 5:39–44).

48. Al-Fath (The Victory):

Revealed after the Treaty of Hudaybiyyah, this chapter describes the peace agreement as a great victory. It highlights God’s support for believers and affirms the Prophet’s mission.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Peace after struggle and God’s provision are shared themes (Romans 5:1, Philippians 4:7).

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: Muhammad is affirmed as the seal of the prophets (33:40), while the New Testament ends prophecy in Christ (Revelation 22:18).

49. Al-Hujurat (The Chambers):

This chapter emphasizes manners, respect, and ethical conduct within the Muslim community. It addresses gossip, suspicion, and tribalism, and affirms that the noblest person is the most righteous.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Warnings against gossip and favoritism are common (James 3:6, James 2:1). Righteousness as the true measure of worth is biblical.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: In the Bible, righteousness is based on faith in Christ, not personal merit (Romans 3:22).

50. Qaf:

A deeply spiritual surah, it urges reflection on death, resurrection, and God’s nearness. It uses vivid imagery to warn of the consequences of heedlessness and to remind listeners of divine accountability.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: God’s omniscience, the resurrection of the dead, and judgment are major biblical themes (Psalm 139, 1 Corinthians 15).

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: In the Qur’an, resurrection is not linked to Christ’s victory over death. There is no assurance of forgiveness through a redeemer.

51. Adh-Dhariyat (The Winnowing Winds):

This surah draws attention to the power of God through natural phenomena. It highlights the fate of past civilizations that denied their messengers and affirms that the purpose of creation is to worship God.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: The Bible also calls creation to testify to God’s power (Psalm 19:1, Romans 1:20). Judgment of rebellious nations is echoed in Genesis and the Prophets.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: The biblical purpose of creation includes fellowship with God and redemption through Christ (Colossians 1:16), not just worship in obedience.

52. At-Tur (The Mount):

Named after Mount Sinai, this chapter presents a vivid picture of the Day of Judgment and contrasts the rewards of the righteous with the punishments for the wicked. It reinforces the truth of revelation and the Prophet’s sincerity.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: The giving of the Law at Sinai and the idea of final judgment are shared (Exodus 19, Hebrews 9:27).

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: The Qur’an does not mention Jesus as mediator of a new covenant, which Hebrews 8–10 teaches as central to the Christian faith.

53. An-Najm (The Star):

This surah opens with a cosmic oath and strongly defends the Prophet’s vision during the Night Journey. It denounces idolatry and calls people to follow divine revelation rather than conjecture.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: The rejection of idolatry and the importance of divine truth are biblical (Isaiah 44:9–20, Galatians 1:6–9).

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: The Prophet Muhammad’s vision is defended here, whereas the New Testament centers divine revelation and authority on Jesus Christ as the image of God (Hebrews 1:1–3).

54. Al-Qamar (The Moon):

Using the recurring example of past nations destroyed for their disbelief, this surah serves as a warning. The splitting of the moon is presented as a sign, and the refrain “And We have certainly made the Qur’an easy to remember” is repeated.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Destruction of disobedient peoples (e.g., Sodom, Egypt) aligns with biblical accounts (Genesis 19, Exodus 14).

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: The miracle of the moon splitting is not found in the Bible. Biblical signs point toward Christ’s coming, not affirming another prophet.

55. Ar-Rahman (The Beneficent):

Known for the refrain “Which of the favors of your Lord will you deny?”, this surah lists God’s blessings and describes both the rewards of Paradise and the punishments of Hell. It emphasizes divine mercy and justice.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: God’s mercy, justice, and provision are celebrated in Psalms (Psalm 103, 145).

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: Paradise in the Bible is entered through union with Christ (John 14:6), not through weighing of deeds as emphasized here.

56. Al-Waqi’ah (The Inevitable):

This chapter categorizes humanity into three groups—the foremost, the people of the right, and the people of the left—and describes their fates. It emphasizes resurrection and the reality of divine judgment.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: The righteous and the wicked are distinguished clearly in both texts (Matthew 25:31–46). Resurrection is a shared theme.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: The “foremost” group and its rewards are described differently. In the Bible, salvation is not stratified by rank or merit but based on grace through faith (Ephesians 2:8–9).

57. Al-Hadid (The Iron):

Balancing themes of spiritual faith and worldly strength, this surah highlights God’s control over the universe. It calls believers to charity, humility, and sincere belief, warning against hypocrisy.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: God’s sovereignty and the call to humility and generosity are consistent with 1 Timothy 6:17–19 and Micah 6:8.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: While both texts promote generosity, the Bible roots giving in the example of Christ’s sacrificial love (2 Corinthians 8:9), not only as a moral command.

58. Al-Mujadila (The Woman Who Disputes):

Named after a woman who brought her complaint to the Prophet, this surah discusses personal disputes, social justice, and God’s awareness of all matters. It condemns secret meetings that promote wrongdoing.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: God’s concern for justice and listening to the marginalized is found in Scripture (Isaiah 1:17, James 5:4).

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: The Qur’an outlines direct social rulings, while the New Testament often appeals to the transformation of the heart through the Spirit (Romans 12:1–2).

59. Al-Hashr (The Exile):

This chapter recounts the expulsion of a Jewish tribe from Medina and describes the qualities of hypocrites. It ends with some of the most beautiful names and attributes of God, calling believers to reflect on divine majesty.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: God’s attributes—merciful, just, sovereign—align with Exodus 34:6 and the Psalms.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: The Bible does not include historical accounts of Muhammad’s time. The Qur’an critiques Jews explicitly here, while the Bible upholds Israel’s covenant, even amid disobedience (Romans 11:28–29).

60. Al-Mumtahanah (The Woman Tested):

Addressing the treatment of non-hostile non-Muslims, this surah emphasizes fairness, the possibility of reconciliation, and the rules concerning alliances and oaths.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Treating outsiders with justice and kindness is encouraged in the Bible (Leviticus 19:34, Matthew 5:43–48).

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: The Qur’an outlines specific political guidance on alliances, while Jesus commands unconditional love and peacemaking even with enemies (Luke 6:27).

61. As-Saff (The Ranks):

This surah encourages unity and discipline among believers, especially in striving for God’s cause. It compares the mission of Prophet Muhammad with that of earlier messengers and warns against hypocrisy in claiming belief without action.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: The call to unity and sincerity in faith parallels Ephesians 4:1–6 and James 2:14–26.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: Jesus is referred to here as foretelling the coming of Muhammad (61:6), which contradicts Christian teaching that Jesus is the final and ultimate revelation (Hebrews 1:1–2).

62. Al-Jumu’ah (Friday):

Emphasizing the importance of the Friday congregational prayer, this surah praises God’s wisdom in sending the Prophet and criticizes those who were entrusted with scripture but failed to uphold it.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: The importance of communal worship is shared (Hebrews 10:25). Scripture as divine trust is emphasized in Romans 3:1–2.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: The Qur’an criticizes earlier scriptural communities for failure, while the New Testament warns but also emphasizes fulfillment in Christ (Matthew 5:17).

63. Al-Munafiqun (The Hypocrites):

This chapter addresses the issue of hypocrisy within the Muslim community. It describes how hypocrites deceive others and warns that God knows their true intentions.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Jesus harshly rebuked religious hypocrisy (Matthew 23), and Paul warned against it (Galatians 2:13).

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: The Qur’an often focuses on community-level consequences; the Bible calls for inward spiritual renewal through the Holy Spirit (Titus 3:5).

64. At-Taghabun (Mutual Disillusion):

This surah contrasts the fate of believers and disbelievers on the Day of Judgment. It reminds listeners that wealth and children are tests, and calls for repentance and trust in God.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Wealth as a test (Matthew 19:23–24) and judgment day teachings (Romans 14:10) are consistent.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: Biblical salvation is not based on balancing deeds but on grace through Christ (Ephesians 2:8–9). The surah does not include Jesus’ redemptive role.

65. At-Talaq (Divorce):

This surah outlines rules for divorce and waiting periods (iddah), emphasizing justice, kindness, and God-consciousness in family matters. It assures that those who trust God will find ease.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Both stress care, fairness, and spiritual awareness in relationships (Malachi 2:16, 1 Corinthians 7).

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: Polygamy and explicit legalistic divorce steps differ from the New Testament’s emphasis on marital permanence and grace-based relationships (Matthew 19:6–9).

66. At-Tahrim (The Prohibition):

Addressing a personal incident in the Prophet’s household, this chapter emphasizes the importance of repentance and warns against betrayal. It also presents the examples of righteous and unrighteous women from history.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Warnings against betrayal (Proverbs 6:32) and exaltation of righteous women (Hebrews 11) are consistent.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: The personal and household context of Muhammad is unique. Biblical focus is on Christ as model and mediator, not the Prophet’s family dynamics.

67. Al-Mulk (The Sovereignty):

This chapter emphasizes God’s control over life and death and invites reflection on the design of the universe. It warns of the punishment for those who reject faith.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: God’s sovereignty and judgment are clear in Psalm 103:19 and Ecclesiastes 12:14.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: The Bible emphasizes God’s sovereignty through Christ (Colossians 1:16–17), a concept not present here.

68. Al-Qalam (The Pen):

Opening with an oath on the pen, this surah defends the character of the Prophet and contrasts him with those who are arrogant and corrupt. It also recounts the story of the people of the garden who were punished for their greed.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Arrogance and greed are condemned (Proverbs 16:18, Luke 12:16–21). Integrity and humility are praised.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: While Jesus is called gentle and lowly in heart (Matthew 11:29), the Prophet’s defense here is uniquely Qur’anic. Biblical revelation is not tied to Muhammad.

69. Al-Haqqah (The Inevitable):

This chapter presents powerful scenes from the Day of Judgment and the destruction of past civilizations. It warns the disbelievers and affirms the truth of the Qur’anic revelation.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Day of Judgment and divine retribution are consistent with Revelation and Matthew 25.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: Salvation and justification are absent here. The Bible centers the final judgment on Christ’s return and atoning work (2 Corinthians 5:10).

70. Al-Ma’arij (The Ascending Stairways):

Describing the reality of the Day of Judgment, this surah highlights human impatience and selfishness while emphasizing that salvation comes through prayer, generosity, and faith.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Warnings against pride and selfishness (James 4:6), as well as judgment and reward, are echoed in Scripture.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: The Qur’an stresses salvation through moral conduct, while the Bible asserts salvation by faith through Christ alone (Titus 3:5, Romans 3:28).

71. Nuh (Noah):

This surah recounts the story of Prophet Noah and his tireless efforts to call his people to monotheism over many years. It highlights Noah’s plea for divine intervention after continued rejection and mockery, and serves as a warning of the consequences of persistent disbelief.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Noah’s long-suffering preaching and the people’s rejection mirror Genesis 6–9 and 2 Peter 2:5. The flood as judgment is shared.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: The Qur’an focuses on Noah’s warning role, with no mention of covenantal rainbow or messianic symbolism seen in 1 Peter 3:20–21.

72. Al-Jinn (The Jinn):

This chapter discusses a group of jinn who listened to the Qur’an and embraced Islam. It emphasizes that jinn, like humans, are responsible for their choices and will be judged. It also reinforces the Prophet’s role as a warner to both realms.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Spiritual beings (angels/demons) are acknowledged in both texts (e.g., Matthew 8:28–32, Job 1:6).

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: The Bible does not describe demons as redeemable or converting. The concept of jinn embracing faith is absent in Scripture.

73. Al-Muzzammil (The Enshrouded One):

Addressing the Prophet directly, this surah urges him to engage in night prayers and spiritual discipline. It transitions into a message for the broader community, stressing patience and readiness to face growing opposition.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Jesus and the apostles practiced prayer at night (Luke 6:12). Vigilance and spiritual discipline are biblical virtues (1 Thessalonians 5:6).

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: The call to follow Muhammad as a spiritual leader is Qur’an-specific. The Bible centers spiritual imitation around Jesus (1 Corinthians 11:1).

74. Al-Muddaththir (The Cloaked One):

Another early call to the Prophet, this surah commands him to rise and warn. It addresses divine judgment, the punishment of the arrogant, and the story of a man who turned away from faith despite receiving guidance.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Prophets like Ezekiel and Jeremiah were similarly called to warn others. Warnings about arrogance and spiritual apathy are also echoed.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: The surah frames Muhammad as the final warner. In the New Testament, Jesus fulfills and closes the prophetic line (Hebrews 1:1–2).

75. Al-Qiyamah (The Resurrection):

Vividly describing the Day of Resurrection, this surah emphasizes the powerlessness of humanity on that day. It defends the Qur’an’s authenticity and calls for reflection on the creation of life and death.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Resurrection and divine judgment are foundational to both faiths (John 5:28–29, Daniel 12:2).

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: In the Bible, Jesus’ resurrection is central and the source of hope (1 Corinthians 15). The Qur’an doesn’t connect resurrection to Christ’s atoning work.

76. Al-Insan (Man):

Also known as Ad-Dahr, this surah reflects on human creation and the capacity for gratitude or denial. It paints a vivid picture of Paradise and its rewards, highlighting the virtues of charity, patience, and sincerity.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Charity and endurance are praised in Proverbs and 1 Corinthians 13. Humanity’s responsibility before God is clear in Romans 1.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: The surah centers on ethical merit and reward, whereas the Bible bases salvation on grace and relationship with God through Christ (Ephesians 2:8–9).

77. Al-Mursalat (The Emissaries):

This chapter begins with oaths on the winds and angels sent with divine commands. It warns of the Day of Judgment and repeatedly affirms the destruction of those who rejected past messengers.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: God’s messengers and warnings of judgment (e.g., Nineveh, Sodom) are common biblical themes (Nahum, Jonah).

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: The New Testament calls not only for warning but for reconciliation through Christ. The Gospel is good news, not just a final warning (2 Corinthians 5:18–19).

78. An-Naba (The Tidings):

It opens with questions about the “great news”—the Day of Resurrection. The chapter details signs of God’s creation and contrasts the fates of believers and deniers, emphasizing accountability.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Judgment Day and moral accountability are shared beliefs (Revelation 20:11–15). Creation pointing to the Creator is found in Romans 1:20.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: In Christianity, the “great news” is Christ’s resurrection and the offer of salvation, not simply judgment.

79. An-Nazi’at (Those Who Drag Forth):

This surah describes the angels who extract souls at death and recounts the story of Moses and Pharaoh. It offers a reflection on resurrection and the ultimate return to God.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: The Exodus story and resurrection themes align (Exodus 5–14; John 11). Angels as servants of God are affirmed in both texts.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: The New Testament emphasizes angels ministering to believers and Christ’s resurrection as the firstfruits—not just a return to God (1 Corinthians 15:20).

80. Abasa (He Frowned):

Revealed in response to an incident involving the Prophet and a blind man, this chapter teaches humility and the value of every soul. It highlights the importance of delivering the message to all, regardless of social status.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: God values the lowly and marginalized (Luke 14:13–14, James 2:1–5). All souls matter equally in God’s sight.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: While both emphasize humility, the Bible centers the ultimate example in Christ’s humility and sacrificial love (Philippians 2:5–8).

81. At-Takwir (The Overthrowing):

This surah uses apocalyptic imagery to portray the end of the world and the reversal of natural order. It urges people to consider the seriousness of divine warnings and affirms the credibility of the Qur’anic message.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: End-time imagery (sun darkened, stars falling) parallels Matthew 24:29 and Revelation 6. The call to heed divine revelation is consistent.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: The New Testament links the end times to Christ’s return and final judgment (Revelation 19–20), which the Qur’an does not reference.

82. Al-Infitar (The Cleaving):

Focused on the breakdown of the cosmos and the exposure of human deeds, this chapter highlights God’s justice. It reminds listeners that everyone has appointed angels recording their actions.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Judgment and record of deeds (Revelation 20:12) are affirmed. Angelic witness and divine justice are biblical.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: In Christianity, believers are justified by Christ, not by the balance of deeds (Romans 3:24–28). The role of angels differs in function and focus.

83. Al-Mutaffifin (Those Who Give Less):

This surah condemns fraud and cheating in trade. It contrasts the fates of the righteous and the wicked and warns of divine punishment for those who mock believers and deny accountability.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: God detests dishonest scales (Proverbs 11:1), and justice for the poor is a biblical priority (Amos 8:5–7).

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: The Qur’an emphasizes moral retribution; the New Testament includes grace even for former sinners (Luke 19:1–10).

84. Al-Inshiqaq (The Splitting):

This chapter discusses the events of the Day of Judgment and the submission of the sky to divine command. It describes the outcomes for those who receive their records in their right versus left hands.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Judgment themes and cosmic obedience to God reflect passages in Revelation and Isaiah 24.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: The right/left-hand imagery is different from the sheep/goats division in Matthew 25. Also, salvation is not based on deeds in Christianity.

85. Al-Buruj (The Mansions of the Stars):

This surah recounts the story of persecuted believers and praises their steadfastness. It assures that God sees all and will punish tyrants and reward the faithful.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Revelation 6:9–11 honors martyrs. God’s awareness and justice are echoed throughout Scripture.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: The Christian martyrs are seen as victorious through Christ’s death and resurrection, not solely through patient endurance.

86. At-Tariq (The Morning Star):

It opens with a cosmic oath and emphasizes God’s knowledge of all things. The chapter underscores human vulnerability and God’s power to resurrect.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: God’s omniscience and resurrection power are central to Christian belief (Psalm 139, 1 Corinthians 15).

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: The “Morning Star” in Revelation (22:16) is a title for Jesus, while in the Qur’an, it’s a symbol of natural wonder with no messianic identity.

87. Al-A’la (The Most High):

A short yet powerful surah glorifying God’s perfection, it reminds believers of the temporal nature of life and the permanence of the Hereafter. It echoes themes of revelation and purification.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: God’s holiness and the call to prepare for eternity reflect Isaiah 40 and Ecclesiastes 12:13–14.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: Purification in the Qur’an is through personal righteousness; in Christianity, it is through the blood of Christ (1 John 1:7).

88. Al-Ghashiyah (The Overwhelming):

This chapter contrasts the faces of the blissful and the damned on Judgment Day. It describes scenes of Heaven and Hell and urges contemplation of God’s signs in creation.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Dual destiny of Heaven and Hell and exhortation to recognize God in nature are biblical (Matthew 25:46, Romans 1:20).

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: Heaven in Christianity is fellowship with God through Christ; the Qur’an describes more physical blessings and lacks reference to a redemptive mediator.

89. Al-Fajr (The Dawn):

Reflecting on the fate of ancient tyrants like Pharaoh and ‘Ad, this surah warns of the danger of arrogance. It ends with a comforting call to the righteous soul: “Return to your Lord, well-pleased and pleasing.”

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Judgment for the arrogant and comfort for the faithful reflect themes from the Prophets and Psalms.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: The Bible connects returning to the Lord with faith in Christ and grace (John 14:6), not simply upright conduct.

90. Al-Balad (The City):

Using Mecca as its backdrop, this chapter speaks of human struggle and the uphill moral path. It defines righteousness as freeing slaves, feeding the hungry, and aiding the downtrodden.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Caring for the poor and freeing the oppressed is central (Isaiah 58, Matthew 25:35–40).

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: Righteousness is grounded in Christ’s atonement, not just social justice. The Qur’an omits the gospel’s spiritual liberation through Christ (Galatians 5:1).

91. Ash-Shams (The Sun):

This surah emphasizes the contrast between good and evil by swearing upon elements of nature. It illustrates the fate of the people of Thamud who denied their prophet, warning that purification of the soul leads to success, while corruption leads to ruin.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: The struggle between righteousness and sin is a core theme throughout Scripture (Romans 7:22–25). God often uses nature as witness (Psalm 19:1).

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: The Bible teaches that purification of the soul comes through Christ, not moral striving alone (Hebrews 9:14, Titus 3:5).

92. Al-Lail (The Night):

Highlighting the moral divergence of human paths, this chapter emphasizes that those who are generous and God-conscious will be eased into goodness, while the stingy and self-sufficient will face hardship.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Scripture upholds generosity and righteousness (2 Corinthians 9:6–7, Proverbs 11:24).

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: Christian teaching focuses on transformation through faith in Christ, not merely good deeds (Ephesians 2:8–9).

93. Ad-Duhaa (The Morning Brightness):

A reassuring surah revealed during a time of pause in revelation, it comforts the Prophet by affirming God’s constant care and promises better outcomes ahead. It encourages kindness to orphans and the needy.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: God’s care in times of silence (Psalm 46:1, Isaiah 41:10) and compassion toward the needy are biblical constants.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: The comfort here is personal and prophetic; in the New Testament, comfort is grounded in the presence of the Holy Spirit and the promises of Christ (John 14:16–18).

94. Ash-Sharh (The Relief):

This brief chapter continues the reassurance from the previous surah, reminding the Prophet of past reliefs following hardship. It inspires patience and perseverance through life’s challenges.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Perseverance through trials is strongly encouraged in Romans 5:3–5 and James 1:2–4.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: While both faiths encourage endurance, the New Testament centers suffering around Christ’s redemptive purpose and presence within suffering (2 Corinthians 12:9).

95. At-Tin (The Fig):

Using the fig, olive, Mount Sinai, and Mecca as symbolic oaths, this surah reflects on human creation and moral potential. It declares that while humanity was created in the best form, it can fall to the lowest unless guided by faith and righteous deeds.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Humanity’s dignity in creation is biblical (Genesis 1:27), as is the need for faith and obedience (Deuteronomy 10:12).

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: Christianity teaches that righteousness is not achieved by works but by grace through faith in Christ (Romans 3:23–24).

96. Al-‘Alaq (The Clot):

This surah contains the first verses revealed to the Prophet, urging the reading and learning in God’s name. It highlights God as the creator and warns against arrogance and rebellion.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: God as Creator and the value of knowledge are affirmed (Proverbs 1:7, Colossians 1:16).

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: Biblical knowledge is centered in Christ, who is the Word made flesh (John 1:1–3, 14).

97. Al-Qadr (The Night of Decree):

Celebrating the night in which the Qur’an was revealed, this chapter declares its superiority over a thousand months and highlights the peace and angelic presence that fills it.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Divine revelation through angels (Luke 1:26–38) and sacred timing are biblical themes.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: The Bible presents its ultimate revelation not in a night or book, but in the person of Jesus (Hebrews 1:1–2).

98. Al-Bayyinah (The Clear Proof):

This surah distinguishes between the followers of earlier scriptures and the disbelievers after the coming of a clear proof. It emphasizes the sincerity of worship and the eternal consequences of belief or denial.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Sincere worship and accountability are core teachings (John 4:24, Romans 2:6–8).

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: The “clear proof” in Islam is the Qur’an and Muhammad’s mission; in Christianity, it is the death and resurrection of Jesus (Romans 1:4).

99. Az-Zalzalah (The Earthquake):

Describing the final earthquake that signals the Day of Judgment, this short chapter emphasizes that every deed, even the smallest, will be accounted for.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: God’s final judgment and attention to all deeds appear in Revelation 20:12 and Matthew 12:36.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: Christianity teaches that judgment for believers is based on Christ’s righteousness, not a balance of personal deeds (2 Corinthians 5:21).

100. Al-‘Adiyat (The Courser):

Swearing by the warhorses that rush into battle, this surah critiques human ingratitude and obsession with wealth. It reminds that on the Day of Judgment, all secrets will be exposed and judged by God.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Warnings against greed and judgment of motives are found in James 5:1–5 and 1 Corinthians 4:5.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: The Qur’an emphasizes fear of exposure and punishment; the Bible teaches both judgment and mercy through Christ (Titus 3:4–7).

101. Al-Qari’ah (The Striking Calamity):

This surah paints a vivid picture of the Day of Judgment with powerful imagery. It highlights the weighing of deeds and the ultimate fate of individuals based on the heaviness or lightness of their scales.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Judgment Day and divine accountability are central in both faiths (Revelation 20:11–15, Romans 14:10).

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: The Bible teaches that justification is based on faith in Christ, not the weight of one’s deeds (Ephesians 2:8–9).

102. At-Takathur (The Rivalry in Worldly Increase):

It warns against being distracted by the pursuit of worldly gain. The chapter stresses that people will be questioned about their blessings and must prepare for the Hereafter.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Jesus warned about storing treasures on earth (Matthew 6:19–21). Accountability for how we handle blessings is affirmed (Luke 12:48).

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: In Christianity, even those who have erred can be restored by grace through repentance—not only through merit.

103. Al-‘Asr (The Time):

A concise surah emphasizing the urgency of time and the conditions for salvation: faith, righteous deeds, truthfulness, and patience.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: The urgency of living wisely and pursuing truth is echoed in Ephesians 5:15–16 and Romans 2:7.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: The Christian view of salvation is grounded not in deeds but in grace through faith (Titus 3:5).

104. Al-Humazah (The Slanderer):

This chapter condemns those who slander others and hoard wealth arrogantly, warning that their end will be in the crushing punishment of Hell.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Slander and greed are condemned in James 3 and Luke 12:20.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: The Bible allows for forgiveness even of such sins when met with repentance (1 John 1:9).

105. Al-Fil (The Elephant):

Recounting the miraculous protection of the Ka‘bah from the army of the elephant, this surah reminds listeners of God’s power to defend His sanctuary and defeat arrogance.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: God’s intervention to protect His people and sacred purposes is found throughout Scripture (Exodus 14, Isaiah 37).

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: This specific event is not mentioned in the Bible, which centers sacred space around the Temple and later the person of Christ (John 2:21).

106. Quraysh:

This brief chapter reminds the tribe of Quraysh of God’s blessings in providing security and sustenance, urging them to worship the Lord of the Ka‘bah.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: God as provider and protector is affirmed throughout the Psalms. Gratitude and worship are recurring commands.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: Worship is directed to God through Jesus in Christianity (John 14:6), not through a geographical site or tribal context.

107. Al-Ma’un (The Small Kindnesses):

It criticizes those who are neglectful in prayer and who withhold simple acts of charity, stressing that religious acts must be matched by social kindness.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Faith without works is dead (James 2:17). Jesus condemns religious hypocrisy (Matthew 23:23).

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: The Qur’an links faith and works more closely in merit; Christianity views good works as fruit, not the basis, of salvation.

108. Al-Kawthar (Abundance):

A short surah affirming the Prophet’s spiritual abundance and encouraging prayer and sacrifice. It contrasts the eternal legacy of the righteous with the obscurity of their opponents.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: God’s blessings and the eventual triumph of the righteous are biblical themes (Psalm 23, Matthew 5:10–12).

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: This surah is specific to the Prophet Muhammad; the Bible centers God’s blessing and legacy on Christ (Philippians 2:9–11).

109. Al-Kafirun (The Disbelievers):

A clear declaration of religious distinction, this chapter emphasizes the principle of mutual respect: “To you your religion, and to me mine.”

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Religious freedom and respecting others’ choices is supported in passages like Romans 14:5 and Matthew 10:14.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: Christianity maintains that Jesus is the only way to God (John 14:6), while this surah expresses peaceful coexistence without theological unity.

110. An-Nasr (The Help):

This surah signals the nearing completion of the Prophet’s mission and the victory of Islam. It calls for praise and repentance as the divine support arrives.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Praise and repentance after success is a recurring biblical theme (Deuteronomy 8:10, Psalm 103:1–5).

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: The completion of mission in the New Testament is centered on Jesus’ death and resurrection, not military or political victory.

111. Al-Masad (The Palm Fiber):

A condemnation of Abu Lahab and his wife, this chapter illustrates that lineage alone does not ensure righteousness or salvation.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Jesus taught that heritage does not guarantee salvation (Matthew 3:9, John 8:39).

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: The Bible warns but rarely names living individuals in such direct condemnation; judgment belongs to God alone (Romans 12:19).

112. Al-Ikhlas (Sincerity):

A profound declaration of monotheism, affirming that God is One, eternal, self-sufficient, and unlike anything else.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: God’s uniqueness and eternal nature are affirmed (Isaiah 40:28, Deuteronomy 6:4).

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: The Christian doctrine of the Trinity is explicitly rejected in this surah (implicit in its emphasis on absolute oneness).

113. Al-Falaq (The Daybreak):

A protective supplication seeking refuge in God from external harms like envy, darkness, and sorcery.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Seeking God’s protection is biblical (Psalm 91, 2 Thessalonians 3:3).

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: Sorcery is rejected in both texts, but the Bible does not include protective prayers of this exact form or emphasis on jinn-like forces.

114. An-Nas (Mankind):

This final chapter seeks refuge in God from internal evils like whispering and temptation, completing the Qur’an with a reminder of divine protection.

- 🟩 Agreement with the Bible: Spiritual warfare and resisting evil influences (Ephesians 6:10–18, James 4:7) align with this message.

- 🟥 Difference from the Bible: The Qur’an does not include the role of Christ or the Holy Spirit as intercessors in overcoming evil.

You must be logged in to post a comment.