A collaboration between Lewis McLain & AI

Why We’re Going Back to the Moon

Not to Repeat Apollo, but to Learn How to Last

When people hear that humanity is “going back to the Moon,” the instinctive response is often puzzled disbelief. We’ve been there. We planted flags. We brought back rocks. Why return now, decades later, at enormous expense, when Earth has so many unsolved problems?

The question is reasonable. The answer is quietly radical.

We are not going back to the Moon to reenact Apollo. We are going back because Apollo solved the problem of arrival. What it did not solve—and never tried to—was the far harder problem of endurance.

Apollo Was a Sprint. This Is a Supply Chain.

The Apollo missions were triumphs of urgency and focus. Engineers built a narrow, brilliant bridge between Earth and the lunar surface, crossed it a handful of times, and then dismantled it. Nothing about Apollo was designed to last. It was a technological moonshot in the most literal sense.

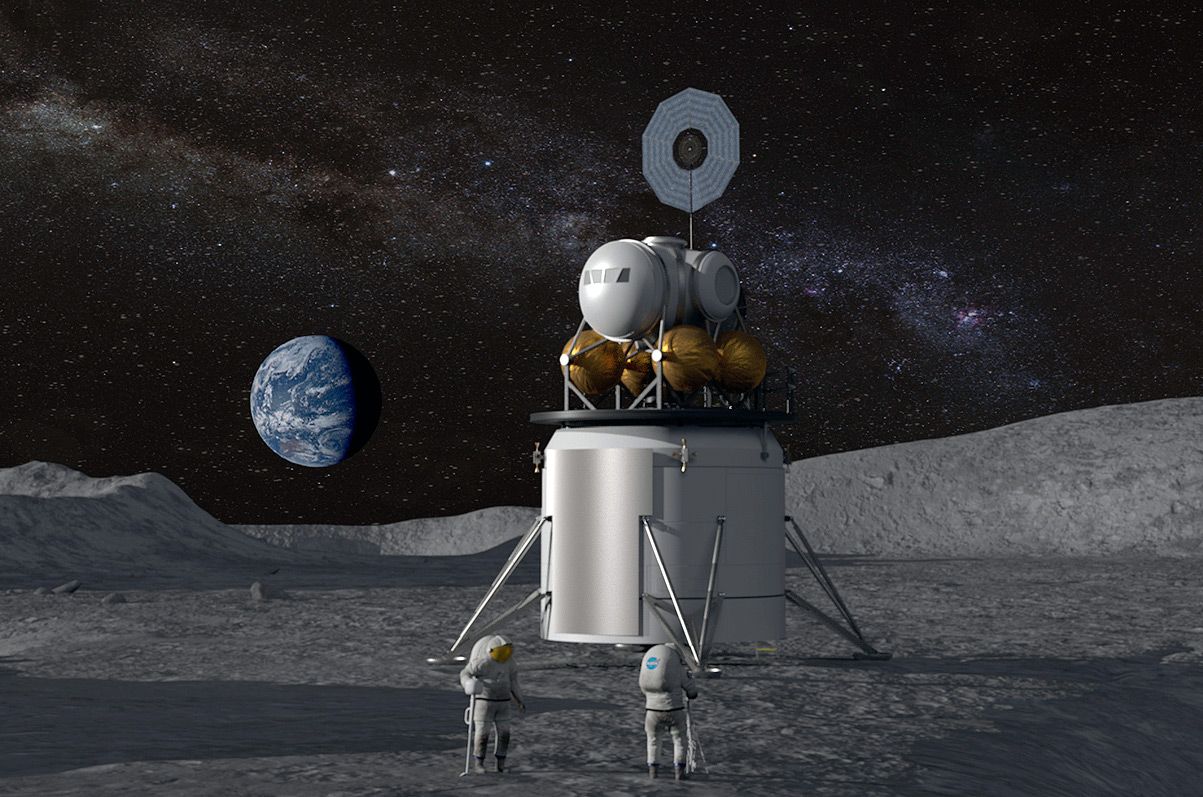

The modern lunar effort, led by NASA through the Artemis Program, has a fundamentally different goal: permanence. Or at least persistence.

This time, the Moon is not the destination. It is the training ground.

The Moon as a Classroom for Survival

The Moon is close—three days away—but it is unforgiving. There is no atmosphere to soften radiation, no weather to erode mistakes, no margin for sloppy engineering. Lunar dust shreds seals and joints. Two-week nights test power systems to their limits. Every failure is exposed, documented, and merciless.

That is precisely why the Moon matters.

If we cannot build habitats, power systems, life support, and logistics chains that function reliably on the Moon, we have no business sending humans to Mars, where rescue is impossible and resupply is measured in years, not days.

The Moon allows us to fail where failure is survivable.

Water Changes Everything

The most consequential discovery of the past two decades is not geological or poetic—it is practical. At the Moon’s south pole, inside permanently shadowed craters, lies water ice.

This transforms the Moon from a dead rock into a strategic asset.

Water is life, but it is also fuel. Split into hydrogen and oxygen, it becomes rocket propellant. That means spacecraft no longer need to haul all their fuel out of Earth’s gravity well. They can refuel in space.

This concept—known as in-situ resource utilization—is the hinge on which deep-space civilization turns. With it, the Moon becomes a refueling station, a logistics hub, and a proving ground for resource extraction beyond Earth.

Without it, Mars remains a stunt. With it, Mars becomes a system.

Building the Architecture of Space

The plan unfolding now is incremental and deliberate.

Humans return to lunar orbit and the surface. Habitats are tested. Power systems endure long nights. Crews learn how isolation really feels when Earth hangs small and distant in the sky. Orbiting infrastructure such as the Lunar Gateway serves as a staging node, teaching us how to operate beyond low Earth orbit for months at a time.

This is not glamorous work. It is infrastructure work. And infrastructure, not heroics, is what makes civilizations durable.

The Strategic Reality No One Likes to Admit

Space is no longer an empty frontier. Other nations are moving quickly, forming partnerships, staking operational claims, and planning long-term presence. Navigation systems, communication relays, resource extraction norms, and orbital traffic management are becoming matters of geopolitics.

Ignoring the Moon would be like ignoring the world’s oceans once ships became global. Space is becoming a domain of activity, not exploration alone. Presence matters—not for conquest, but for competence.

Why Not Just Go Straight to Mars?

Because Mars is a one-way exam with no retakes.

A Mars mission requires years of flawless life support, radiation protection, psychological resilience, and autonomous repair. The Moon lets us rehearse those requirements under real conditions, with real consequences, while still allowing return.

Skipping the Moon would not be bold. It would be reckless.

The Deeper Reason Beneath the Engineering

There is a quieter truth beneath all the policy papers and mission timelines.

Civilizations stagnate when they stop expanding their operational horizon. Not their fantasies—their capabilities. The Moon forces us to confront what it actually takes to live beyond Earth, not just visit it.

Apollo proved that humans could reach another world. Artemis asks a more unsettling question: can we build systems that outlast individual missions, administrations, and generations?

Going back to the Moon is not nostalgia. It is rehearsal.

And rehearsals are what make the future survivable.

The Moon program is called Artemis for a reason that is at once mythological, symbolic, and quietly deliberate.

In Greek mythology, Artemis is the goddess of the Moon, wilderness, and the hunt. She is also the twin sister of Apollo, the god of the Sun.

That sibling relationship is the key.

Apollo Had a Twin All Along

NASA’s original Moon missions in the 1960s were called Apollo program, named for the sun god—appropriate for an era defined by boldness, visibility, and raw technological firepower. Apollo was about speed, dominance, and proving capability under pressure.

But mythology never told a one-sided story. Apollo always had a twin.

Artemis, unlike her brother, was not associated with conquest or spectacle. She was a guardian of thresholds: forests, animals, young life, and the quiet rhythms of nature. She moved through harsh terrain with patience and precision. She survived.

When NASA named the modern lunar effort the Artemis Program, the message was subtle but intentional:

this is not Apollo reborn—it is Apollo’s counterpart.

A Name That Signals a Shift in Purpose

Apollo answered the question: Can we get there?

Artemis asks a different one: Can we live there?

The name reflects that shift. Artemis is about endurance rather than arrival, systems rather than stunts, continuity rather than closure. In myth, she roamed wild, unforgiving places and mastered them without trying to dominate them. That is exactly the posture required for long-term life beyond Earth.

There is also a human layer to the symbolism. Artemis is female, and the program explicitly includes landing the first woman and the next man on the Moon. But the symbolism runs deeper than representation. It signals balance—between ambition and restraint, power and sustainability.

Myth as Engineering Language

NASA has always borrowed from myth not as decoration, but as shorthand for purpose. Mercury, Gemini, Apollo—each name encoded a philosophy.

Artemis completes the story Apollo began.

The twin returns to the Moon not in a blaze of novelty, but with the quieter ambition of staying, learning, and building something that does not immediately vanish when the mission ends.

In that sense, the name is not poetic fluff. It is a mission statement disguised as mythology.

Apollo showed us how to touch another world.

Artemis is about learning how not to let go.