A collaboration between Lewis McLain & AI

January 11 is not a date that shouts. It doesn’t clang with bells like Christmas or blaze with candles like Easter. Instead, it stands quietly at the hinge of the Christian year, often bearing the Feast of the Baptism of the Lord, the moment when the Church turns from the mystery of Christ’s birth to the meaning of his mission. Historically, this date gathers together theology, liturgy, and the lived practices of the early Church in a way that is subtle—but foundational.

From Epiphany to the Jordan

In the earliest centuries, the Church did not separate Christmas, Epiphany, and the Baptism of the Lord as neatly as later calendars would. Epiphany—the “appearing” or manifestation of God in Christ—was originally a single, sweeping celebration. It included the visit of the Magi, the wedding at Cana, and, crucially, the baptism of Jesus in the Jordan River.

By late antiquity, Western Christianity began to distribute these themes across the calendar, while Eastern churches retained a more unified Epiphany focus on baptism. January 11, when it hosts the Baptism of the Lord, thus echoes this ancient layering: a reminder that Christ is revealed not only in a manger, but in water, voice, and Spirit.

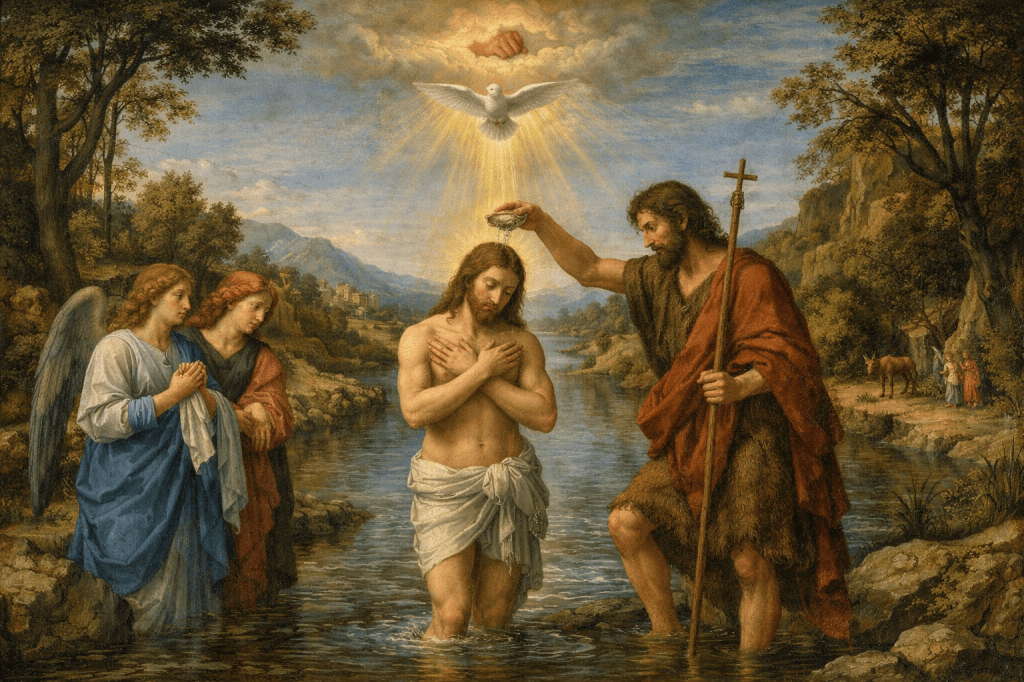

The Gospel accounts describe Jesus Christ stepping into the Jordan to be baptized by John the Baptist—an act that puzzled early theologians. Why would the sinless submit to a baptism of repentance? The Church Fathers answered not with logic alone, but with poetry and paradox: Christ enters the waters not to be cleansed, but to cleanse them.

Baptism Before There Were Baptisteries

For the early Church, this event was not merely historical; it was instructional. Baptism was the doorway into Christian life, often performed in rivers, lakes, or communal baths. Converts descended naked into the water, symbolically dying to their former life, and rose to be clothed in white—an enacted theology that echoed Christ’s own descent and rising.

January 11 therefore became a catechetical moment. Sermons preached around this feast explained what baptism meant: death and rebirth, adoption into God’s family, and incorporation into a community that spanned heaven and earth. This is why ancient lectionaries pair the Baptism of the Lord with readings about light, calling, and divine sonship. The Church was teaching people who they were, not merely what they believed.

The Voice, the Dove, and the Trinity

Church history shows a growing theological depth attached to this feast. By the fourth century, writers like Gregory of Nazianzus emphasized that Christ’s baptism is one of the clearest Trinitarian moments in Scripture: the Son in the water, the Spirit descending like a dove, and the Father’s voice declaring, “You are my beloved Son.”

This mattered profoundly in centuries when the Church was clarifying doctrine against confusion and heresy. January 11 was not abstract theology; it was a calendar-anchored confession of who God is. Long before creeds were memorized by congregations, the liturgical year taught doctrine by repetition and rhythm.

Saints Who Lived the Meaning

January 11 also carries the memory of saints whose lives embodied baptismal commitment. Among them is Theodosius the Cenobiarch, a fifth-century monastic leader who organized communal monastic life in Palestine. His title, “Cenobiarch,” means ruler of the common life—a reminder that baptism was never meant to be private spirituality. It was a public reorientation of life toward discipline, service, and shared obedience.

The Church’s habit of pairing major theological feasts with saint commemorations is not accidental. Doctrine becomes flesh in people. Baptismal vows take shape in monasteries, parishes, hospitals, and households.

January 11 as a Threshold

Historically, January 11 marks a turning. The Christmas cycle closes. Ordinary Time approaches. The infant in the manger is now revealed as the Son sent into the world. In church history, this date has functioned as a kind of spiritual handoff—from wonder to work, from revelation to responsibility.

The Church has long understood that faith cannot live forever in the glow of Christmas light. It must step into colder water. January 11 reminds Christians that the story does not move from birth straight to glory, but through obedience, humility, and vocation.

In that sense, this quiet date carries enormous weight. It tells the Church, year after year, that Christianity begins not with achievement, but with descent—into water, into community, into a calling that unfolds across time.

Happy Birthday to sister-in-law, Diane!