A collaboration between Lewis McLain & AI

January 10 is not remembered for a single dramatic event. It is remembered because, across different centuries, it marks moments when people refused to accept what had long been treated as inevitable. In 1776, political authority was stripped of its mystique. In 1920, war itself was treated as a solvable problem. And in 1914, geography was no longer allowed the final word.

Ideas came first. Then institutions. Then earth itself.

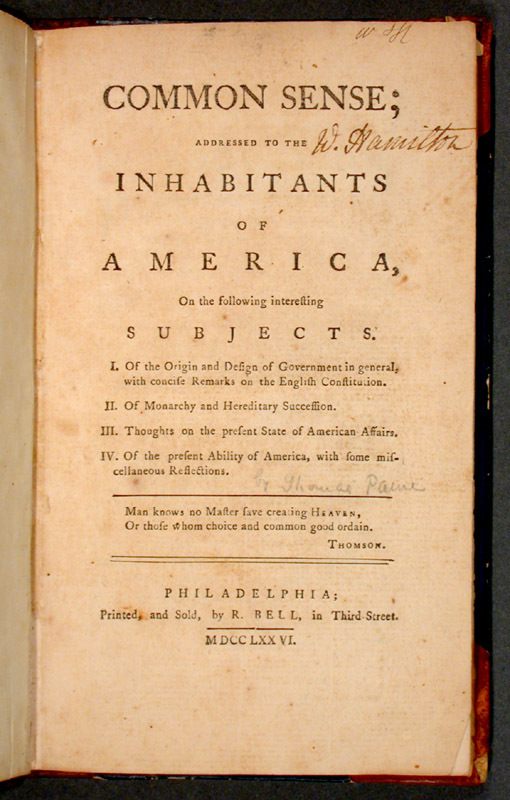

Common Sense: The Dangerous Simplicity of Clarity (1776)

On January 10, 1776, Common Sense was published anonymously. Its author, Thomas Paine, did not argue like a philosopher addressing kings. He argued like a citizen addressing neighbors.

Paine’s brilliance was his refusal to dress radical ideas in polite language. One of his opening claims cut straight through inherited reverence:

“Government, even in its best state, is but a necessary evil; in its worst state, an intolerable one.”

Monarchy, Paine argued, was not merely unjust—it was inefficient. It solved no problem that could not be solved better by representative government. His psychological insight may have been even sharper:

“A long habit of not thinking a thing wrong gives it a superficial appearance of being right.”

Here Paine identified the real obstacle to reform: habit. People obey systems not because they are good, but because they are familiar. By naming that habit, Paine broke it. George Washington observed that Common Sense “worked a powerful change in the minds of many men.” The revolution did not begin on January 10—but on that day it acquired its moral grammar.

The League of Nations: Civilizing Power After Catastrophe (1920)

On January 10, 1920, the League of Nations met for the first time. Europe was exhausted, scarred by mechanized slaughter on an unprecedented scale. The League’s founding premise was quietly radical: war was not a right of nations, but a failure of systems.

The League sought to replace secret treaties and balance-of-power maneuvering with transparency, arbitration, and collective security. Disputes would be discussed before they turned violent. Aggression would meet unified resistance. Peace would be managed, not hoped for.

The institution failed in its ultimate task. It lacked enforcement power. Consensus rules slowed action. The absence of the United States weakened legitimacy. Yet the League permanently altered expectations. War was no longer treated as inevitable or honorable; it was treated as preventable and shameful.

Like Common Sense, the League did not solve the problem it named—but it changed how the problem was understood. Its structure, language, and lessons would later be carried forward into successor institutions built with harder edges.

The Panama Canal: Two Attempts, One Transformation (1914)

On January 10, 1914, the Panama Canal opened to commercial traffic. Unlike the pamphlet or the treaty hall, this achievement came only after failure, scandal, and staggering loss of life.

The French attempt (1881–1889): vision without realism

The first effort was led by Ferdinand de Lesseps, celebrated for the Suez Canal. Confident that Panama would yield to similar methods, the French attempted a sea-level canal. They underestimated the terrain, the rainfall, and the earth itself.

Even more fatal was disease. Yellow fever and malaria ravaged the workforce. Landslides repeatedly refilled excavated sections, particularly in what would later be called the Culebra Cut. Financial mismanagement and corruption scandals in Paris sealed the project’s collapse. By 1889, the effort was abandoned, leaving behind equipment, graves, and a warning.

The American effort (1904–1914): engineering, medicine, discipline

The United States took control in 1904. The approach was fundamentally different. The design shifted to a lock-and-lake system, lifting ships about 85 feet above sea level to cross the isthmus via Gatun Lake.

Equally transformative was public health. Under William C. Gorgas, mosquito control, sanitation, and clean water systems drastically reduced disease. For the first time, sustained work was possible.

Engineering leadership also mattered. John F. Stevens stabilized operations and logistics. George Washington Goethals drove the project to completion with military precision.

Scale and cost

- Length: about 51 miles (82 km)

- Lift: approximately 85 feet above sea level

- Workforce: over 40,000 laborers

- Cost (U.S. phase): roughly $375 million

- Total deaths (French + U.S. efforts): more than 25,000

The canal permanently shortened global shipping routes by thousands of miles. Naval strategy, trade flows, and port cities were reshaped overnight. Once completed, the world became functionally smaller—and it could not return to its former scale.

The Unifying Thread

Paine questioned the inevitability of monarchy.

The League questioned the inevitability of war.

The canal questioned the inevitability of distance—and required failure before success.

January 10 reminds us that progress is rarely clean. It is argumentative, experimental, and often built on earlier mistakes. But when ideas, institutions, and engineering align, even the oldest assumptions—about power, conflict, and geography—can be rewritten.