A collaboration between Lewis McLain & AI

Actually, my first financial models were on green 13-columnar tablets. If you know what I am talking about, I can get pretty close guessing your age.

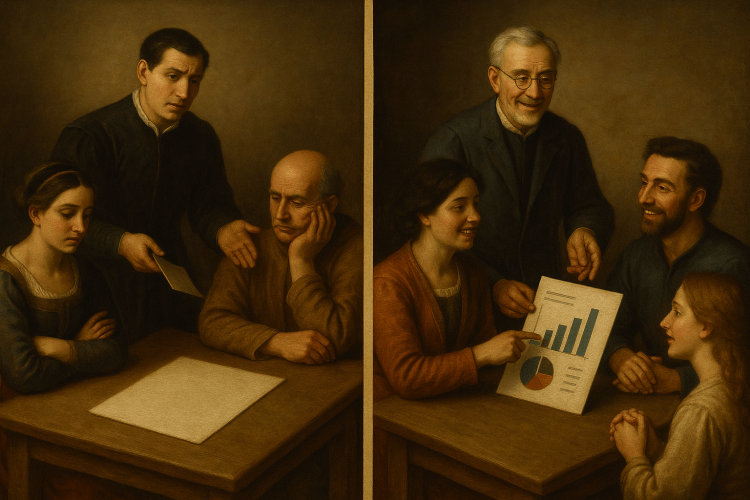

Most people assume that good analysis starts with a team gathered around a whiteboard, freely offering numbers, assumptions, and ideas. In theory, it sounds collaborative and egalitarian. In reality, that moment — the blank sheet of paper — is where analysis dies. People freeze. Smart, capable, experienced people who absolutely know their business suddenly say nothing when asked to put the first assumptions down.

Early in my career, I tried it the traditional way. I’d walk into a meeting ready to do things “the right way”: engage the group, ask for their best estimates, encourage open discussion. Instead, I got silence. Eyes drifted to the table. Pens clicked. People “would have to get back to me.” Suddenly, no one knew anything. It was as if asking someone to write the first number turned the room into a library reading room during finals week — quiet, anxious, and deeply unproductive.

It took me years to understand the psychology behind this. People aren’t reluctant because they lack insight. They are reluctant because they are afraid of owning the first mistake. The first assumption is the most vulnerable one. Once it is written down, it looks like a position, a commitment, a claim to be defended. And for many professionals — especially those who are cautious, political, or simply overwhelmed — that’s not a place they want to stand.

So, I developed a different approach. I stopped asking for the first draft of ideas and assumptions.

I started building the entire model myself — the assumptions, the structure, the logic, the forecasts — everything. I would take the best information I had, make the best reasonable assumptions I could, and produce a full version. Not a sketch. Not a preliminary worksheet. A full, working model.

Then I would send it to the very people who declined to give me assumptions and simply ask:

“Would you please critique this?”

That one sentence changed everything.

Why Critiquing Works When Creating Doesn’t

Something very human happens when someone is handed a complete model or draft of a report. The reluctance melts away. The fear of being wrong diminishes. The instinct to avoid being “first” is replaced by the instinct to correct, to improve, to clarify, to argue, to refine.

People who gave me nothing on a blank sheet suddenly became:

- Detailed

- Insightful

- Opinionated

- Protective of accuracy

- Willing to explain nuances they never would have volunteered earlier

The entire room would come alive.

I used to think this was a flaw — that people should be willing to start from scratch. But then I realized the truth: starting is the hardest intellectual act in any field. Creation is vulnerable; critique is safe. The blank page is intimidating; a flawed draft is an invitation.

And here is the real secret:

People are most honest when they are correcting you.

They will tell you the real revenue figure.

They will tell you why an assumption is politically impossible.

They will tell you which number has never made sense.

They will tell you what they truly believe once you’ve already said something they can push against.

Ironically, by giving them something to disagree with, I got the truth I was searching for.

The Picker–Pickee Method for Analytical Work

I call this my “picker–pickee” method (AI hates my term) — not in the social sense of drawing people into conversation, but in the analytical sense of drawing them into ownership. I pick the model. They pick it apart. And in that exchange, we arrive at what I needed all along:

Their actual knowledge.

Their real assumptions.

Their unfiltered expertise.

Without forcing them to start from zero.

Why This Technique Became One of My Career Signatures

Over time, I realized this was more than a workaround. It was a strategic advantage.

- It accelerated projects.

- It produced better numbers.

- It revealed hidden politics and constraints.

- It allowed people to save face while still contributing.

- It created buy-in because the team helped “fix” the model.

- It insured that the final product reflected collective wisdom, not my isolated guesswork.

I stopped apologizing for this method. I embraced it. I refined it. And eventually I came to see it as one of the most reliable tools in my entire professional life.

Because the truth is simple:

People don’t want to write the first word, but they will gladly edit the whole paragraph.

If you want real input from reluctant contributors, do the hard part yourself. Build the model. Write the draft report. Take the risk. Put the first assumptions on the page. And then ask for critique — sincerely, humbly, and openly.

They will show you what you needed to know all along.

Closing Reflection

If there is any lesson I wish I had learned earlier, it is this:

You don’t get better analysis by demanding contribution.

You get better analysis by giving people something to respond to.

Once I accepted that, my work changed. My relationships with stakeholders changed. And the quality of every model I built improved dramatically.

It may not appear in textbooks, but after decades of practice, this remains one of my most effective — and most human — secrets of the profession.