Influenced by Dan Johnson, Written by Lewis McLain & AI

“The hunger for truth is the only need that can quiet the hunger for more.”

Introduction – The Philosophers and the Question of Desire

Long before the modern world filled with advertising and endless choice, three Greek philosophers—Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle—asked a question that still shapes every generation: What do people truly need to live well, and what do they merely want?

These men lived in the fifth and fourth centuries before Christ, centuries before the New Testament and before the Hebrew Scriptures were widely known in Greek. The Old Testament had already been written, but it existed mainly in Hebrew. The first Greek translation—the Septuagint—would not appear until about 250 BC, long after their deaths.

Thus, any harmony between their philosophy and Scripture is not influence but convergence—the meeting of human reason and divine revelation along parallel paths of wisdom. Each of these men sought meaning in an age of moral confusion and spiritual hunger, tracing a journey from ignorance to illumination, from appetite to understanding, from want to need. They remind us that wisdom is not born in comfort, but discovered in questioning.

Socrates: The Questioner of the Soul

Socrates (469–399 BC) is often called the father of Western philosophy. He wrote nothing himself; instead, he taught through conversation, walking the streets of Athens and engaging anyone who would listen. He used what we now call the Socratic Method—a disciplined form of dialogue built on relentless questioning. For Socrates, teaching meant guiding others to uncover truth already within them.

He believed that wisdom begins not in knowledge but in humility—the honest recognition of one’s own ignorance. To know that one does not know, he said, is the beginning of wisdom. That attitude set him apart from the arrogant teachers and politicians of his day. His conversations often exposed the ignorance of the powerful, earning him both admiration and enemies.

When Athens put him on trial for “corrupting the youth” and “disrespecting the gods,” he refused to abandon his convictions. He was offered a chance to flee, but declined. Instead, he calmly drank the hemlock and died in peace, choosing truth over life itself. “The unexamined life,” he said, “is not worth living.” In those words, he transformed death into testimony.

His courage mirrors the timeless wisdom of Proverbs 4:7: “Wisdom is the principal thing; therefore get wisdom.” Though separated by centuries and culture, both Socrates and Scripture call humanity to put truth above comfort. He believed that wrongdoing came not from evil intent but from ignorance—because no one who truly knows the good would deliberately choose the bad. For him, virtue and knowledge were inseparable. Evil was a shadow cast by misunderstanding.

In that light, Socrates stands as the first great physician of the soul. He asked questions not to embarrass, but to heal. His method endures as a call to honest reflection: before we seek wealth, honor, or pleasure, we must first ask, What is right? What is true? And only then can we ask, What is enough?

Plato: The Philosopher of Light

Plato (427–347 BC), Socrates’ most devoted student, inherited his teacher’s passion for truth and turned it into a philosophy of the eternal. He founded The Academy—the first great university of the Western world—and sought to understand the nature of reality itself. For Plato, everything visible was merely a reflection of something invisible, a shadow of a higher pattern he called a Form.

To Plato, this visible world was a realm of change and illusion, while the unseen world of Forms was eternal and perfect. Among these Forms, one stood above all: The Good—the source of all truth, beauty, and justice. Just as the sun allows the eye to see, the Good allows the mind to know. The human soul’s greatest need, Plato said, is to turn away from the shadows of appearance and face the light of the Good. Only then can it find peace.

This teaching finds a surprising parallel in Scripture: “Do not store up for yourselves treasures on earth, where moth and rust destroy, but store up treasures in heaven” (Matthew 6:19–21). Both urge us to look beyond temporary possessions toward what endures forever.

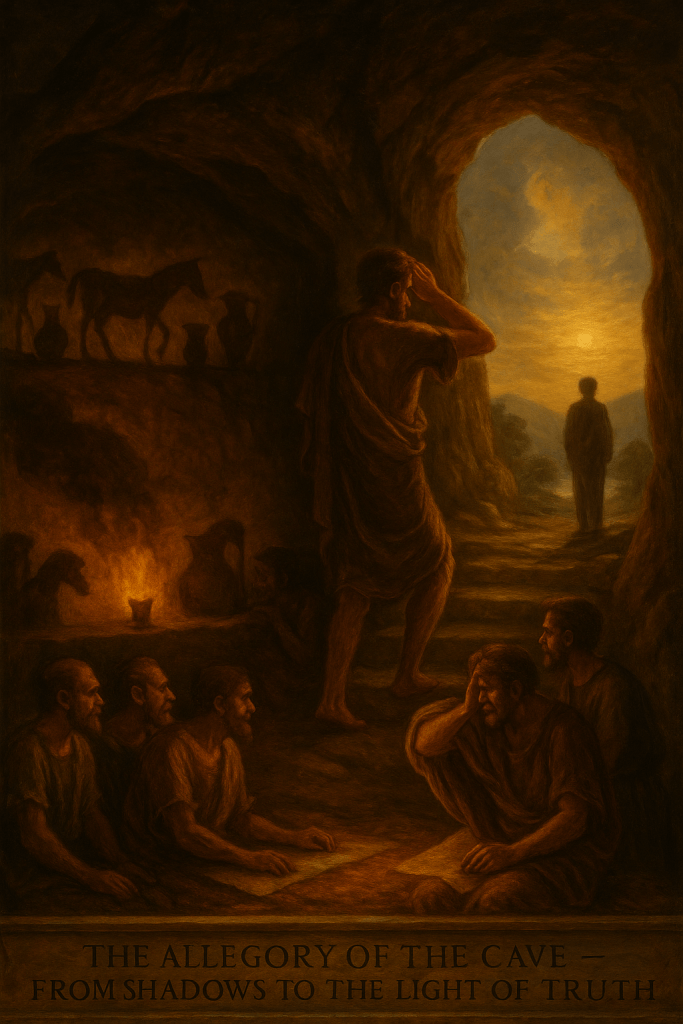

The Allegory of the Cave

In his most famous story, Plato imagines a group of prisoners chained since birth in a dark cave. Behind them burns a fire, and between the fire and the prisoners, other people carry objects along a wall. The captives can see only the shadows cast on the wall before them—and to them, those shadows are reality. They have never seen the world beyond the cave.

Then one prisoner is freed. The light blinds him at first. The path upward is painful. But when he finally emerges into the sunlight, he sees the true world—trees, mountains, rivers, and the sun itself. He realizes that what he once thought was real was only an imitation. Filled with wonder, he returns to free the others, but they laugh, mock, and threaten him. They prefer the familiar comfort of darkness to the painful brightness of truth.

The cave is ignorance; the fire is illusion; the sun is the light of truth. Yet Plato’s story is not just intellectual—it is moral and emotional. The freed man must leave behind friends who are content with shadows. His return to the cave, only to be rejected, mirrors the prophet’s calling and Christ’s rejection by those who preferred darkness to light.

As Jesus said in John 8:12, “I am the light of the world. Whoever follows me will not walk in darkness, but will have the light of life.” The parallel is clear: both call humanity from illusion to reality, from fear to faith, from want to need. Plato’s freed prisoner is not merely a thinker; he is a convert, reborn by enlightenment.

Aristotle: The Philosopher of Balance

Aristotle (384–322 BC), Plato’s greatest student, was more practical than his master. Where Plato looked to heaven, Aristotle looked to the world around him. He believed that knowledge begins in experience, not abstraction. He saw nature as a teacher, and reason as humanity’s greatest tool for understanding it.

In Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle asks what makes a life truly good. His answer is eudaimonia—a word meaning “flourishing” or “well-being.” True happiness, he argued, is not pleasure or wealth but the full development of virtue, the fulfillment of one’s purpose.

Every human, he said, has a telos, or end—a natural goal. Just as an acorn’s purpose is to become an oak, a human’s purpose is to live according to reason and virtue. Happiness is achieved not by accident but by consistent moral effort. It is a lifelong practice, not a passing mood. Virtue, Aristotle insisted, is a habit formed through discipline.

He also taught that virtue lies in balance—the Doctrine of the Mean. Every moral quality, he said, stands between two extremes. Courage is the balance between cowardice and recklessness. Generosity lies between stinginess and extravagance. Self-control lies between indulgence and indifference. The virtuous person does not destroy desire, but masters it. Reason is not the enemy of feeling—it is its guide.

Aristotle also divided life’s goods into three levels.

The first were external goods—wealth, reputation, and possessions—useful, but unstable. Fortune could give and take them away.

The second were bodily goods—health, rest, and safety—necessary, but not sufficient for happiness.

The third and highest were goods of the soul—virtue, wisdom, friendship, and contemplation. These are lasting, self-contained, and fulfilling. Only when these are cultivated can a person live well, regardless of circumstance.

This harmony of thought aligns beautifully with Philippians 4:11–13, where Paul writes: “I have learned to be content whatever the circumstances… I can do all things through Christ who strengthens me.” Both the philosopher and the apostle teach that contentment does not depend on abundance but on order—the soul’s alignment with truth.

Aristotle also reasoned that all motion must have a cause. Tracing this logic backward, he concluded that there must be a Prime Mover—a perfect being that moves all things without itself being moved. Centuries later, Thomas Aquinas identified this Prime Mover as God. Reason, Aristotle showed, is a lamp bright enough to reach the edge of revelation.

The Philosophical Continuity

Together, these three philosophers form one continuous ascent of thought. Socrates questioned falsehood and awakened conscience. Plato sought eternal reality and called the soul toward the light. Aristotle translated that vision into practice, showing how to live wisely in the world.

One generation asked the question, the next envisioned the answer, and the third applied it to daily life. They represent humanity’s climb toward wisdom—a spiritual evolution from ignorance to understanding, from confusion to clarity. Their ideas shaped not only philosophy but law, science, and faith. When early Christian theologians sought to express divine truth in rational form, they turned to the tools these men had forged.

Shared Wisdom and Biblical Harmony

Though they lived before Christ, Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle echoed the moral melody later perfected in Scripture. Socrates’ relentless pursuit of wisdom anticipates Proverbs 9:10: “The fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom.” Plato’s longing for unseen reality parallels 2 Corinthians 4:18: “We fix our eyes not on what is seen, but on what is unseen.” Aristotle’s insistence on moderation and moral character reflects Micah 6:8: “To act justly, to love mercy, and to walk humbly with your God.”

Their voices rise from different centuries and languages, but their harmony is unmistakable. Each saw that human desire must be ordered by a higher principle—that the path to fulfillment runs through discipline, reflection, and faith. Their shared message is timeless: wants are endless, but needs are purposeful.

Wants gratify; needs transform. Wants fade like shadows; needs form the soul.

The Meeting of Athens and Jerusalem

Centuries later, early Christian thinkers recognized that the light these philosophers glimpsed was the same light Scripture revealed. Justin Martyr and Clement of Alexandria, two of the earliest theologians to engage Greek philosophy, believed that reason itself was a divine gift that led humanity toward God. Justin called philosophy “the schoolmaster that leads the mind to Christ,” and Clement wrote that faith and reason are “two wings of the same truth.”

When the Septuagint—the Greek translation of Hebrew Scripture—was completed, it became a bridge between cultures. Athens could finally hear Jerusalem, and Jerusalem could answer Athens. What Socrates sought, what Plato imagined, and what Aristotle reasoned, the Gospel fulfilled in Christ, “the true Light that gives light to everyone” (John 1:9).

The Allegory in Life: From Shadows to Light

Every person, Plato might say, lives in some version of the cave—chained not by iron but by illusion. We mistake image for substance, approval for love, comfort for peace. The modern world projects its own shadows on our walls: screens glowing with distraction, news cycles that amplify fear, and wealth that masquerades as worth. Yet the call upward remains the same. The climb is steep, but the light is steady.

Faith completes what philosophy began. The light beyond the cave is not abstract Goodness—it is Christ Himself.

“For God, who said, ‘Let light shine out of darkness,’ made his light shine in our hearts” (2 Corinthians 4:6).

The soul’s journey from ignorance to illumination is not only the story of reason—it is the story of redemption.

Modern Reflection: Living Between Desire and Discipline

Socrates still whispers, “Question your assumptions.” Plato still calls, “Lift your eyes toward what is eternal.” Aristotle still teaches, “Live in balance and virtue.” And Scripture gathers their insights into a single command: “Seek first the kingdom of God and His righteousness, and all these things will be added to you” (Matthew 6:33).

In a culture of appetite, their words form an antidote. True happiness is not the freedom to want everything—it is the wisdom to need only what is good. Their combined witness forms a bridge from philosophy to faith, from knowledge to love.

Epilogue: The Climb Continues

Imagine Socrates questioning beneath the fig tree, Plato pointing upward toward the sunlight, and Aristotle sketching circles of balance upon the sand. Together they stand at the mouth of the cave as dawn breaks, their faces warmed by the same light that would later shine in Bethlehem. Their search for truth ends where revelation begins—in the light that does not fade.

In that light, wants fall silent. The soul finally rests, not in what it owns, but in Who it has found.

Reflective Poem – “The Light Beyond the Cave”

In the cave we chase our shadows,

mistaking flickers for the flame.

The chains we wear are woven of comfort,

our blindness praised by name.But one climbs upward through the darkness,

eyes stung, heart stripped, soul torn.

He finds the sun, and trembling whispers,

“I see what I was made for, born.”O Light of Lights, O Truth that calls,

unbind us from this clever grave.

Teach us to need what time can’t steal—

and seek the light beyond the cave.

Footnotes

- The Septuagint: The first major Greek translation of the Hebrew Scriptures, completed around 250 BC in Alexandria. It allowed Jewish and Greek intellectual worlds to meet, paving the way for the New Testament’s language and for Christian theology’s dialogue with Greek philosophy.

- Justin Martyr (100–165 AD): An early Christian apologist and philosopher born in Flavia Neapolis (modern Nablus). Originally a student of Greek philosophy, he converted to Christianity and defended it using reason. He was executed in Rome for refusing to renounce his faith.

- “Martyr” was not his surname but an honorary title meaning “witness.” In Greek, μάρτυς (martys) described someone who testified to the truth, often unto death. Thus, “Justin Martyr” literally means “Justin the Witness.”

- Clement of Alexandria (c. 150–215 AD): A theologian and head of the catechetical school in Alexandria, Egypt. Deeply trained in philosophy, he taught that reason and revelation both come from God. Clement described philosophy as a “covenant gift,” preparing the Gentile world for Christ.