Written by AI Based on Questions From Lewis McLain

Strategic Situation, Economic Profile, and Global Implications

Executive Summary

What is the deal with Madagascar? I wasn’t quite sure where it was until I heard about the military taking over the government today. I prepared this paper today as if I had been asked to brief an executive on any subject. As a student of government, I had questions. AI helped me get the answers, so here we go.

Madagascar stands at a turning point. After months of youth-led protests and a mutiny by the CAPSAT (1) elite military unit, President Andry Rajoelina was impeached and fled the country. A military council now governs and has suspended the courts and commissions, promising a new constitutional order within two years.

Commanding the Mozambique Channel, the island anchors the trade corridor linking Africa, the Middle East, and Asia. Its economy is built on vanilla, nickel, cobalt, ilmenite, and gold—resources that feed global supply chains from food flavoring to electric vehicles. The direction of its transition will determine whether the western Indian Ocean tilts toward democratic recovery or prolonged military dominance.

1 | Strategic Importance

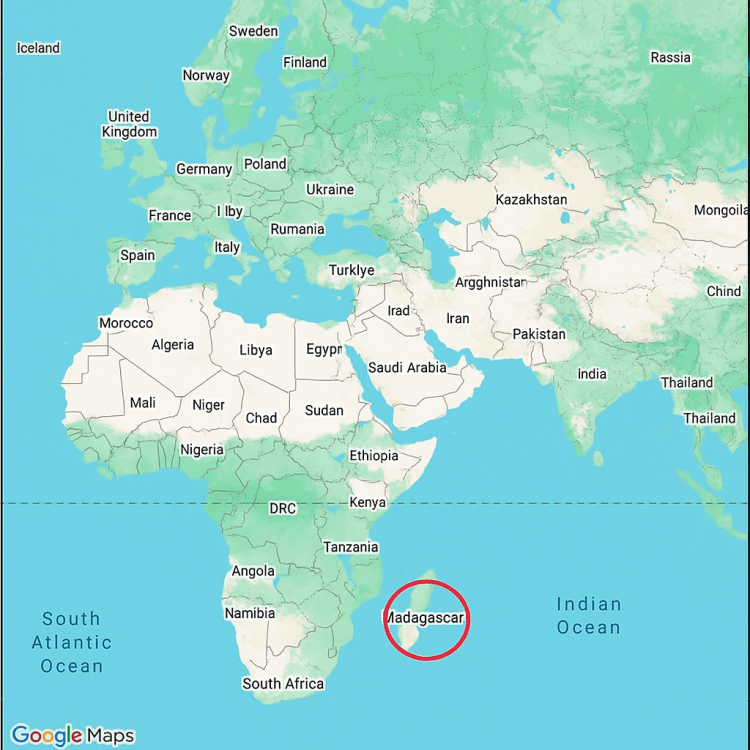

Madagascar occupies a central position in the southwest Indian Ocean, east of Mozambique and west of Réunion and Mauritius.

Covering 587,000 km², it is roughly 45 percent larger than California or almost the size of Texas, with about 31 million inhabitants and the capital at Antananarivo.

Its location astride the Mozambique Channel gives it influence over one of the world’s busiest maritime arteries—used by oil tankers, container ships, and subsea cables. Whoever governs Madagascar shapes the security of sea-lanes vital to East Africa, the Persian Gulf, and South Asia.

2 | Historical Overview (1960 – 2025)

Independence and Early Instability (1960–1972)

Madagascar gained independence from France on 26 June 1960 under President Philibert Tsiranana, whose moderate, pro-French government preserved economic ties to Paris. By the early 1970s, discontent over inequality, rural neglect, and perceived neo-colonialism triggered strikes and mass protests. In 1972, Tsiranana ceded power to the army under Gen. Gabriel Ramanantsoa, inaugurating a cycle of military influence that still echoes today.

Authoritarian Experiment (1975–1991)

After a brief interim, Col. Richard Ratsimandrava was assassinated only six days into office. Admiral Didier Ratsiraka then consolidated control, founding the socialist-leaning Second Republic in 1975. His “Red Book” of revolutionary socialism nationalized industry and aligned Madagascar with the Soviet bloc and North Korea.

Initial enthusiasm faded as the economy collapsed under state planning, corruption, and isolation.

Democratic Opening and Backlash (1991–2002)

Mass demonstrations in 1991 forced political liberalization and the adoption of a new constitution. Albert Zafy became the first democratically elected president but was impeached in 1996 amid corruption allegations. Ratsiraka returned in 1997, attempting liberal reforms without restoring trust.

The disputed 2001 election between Ratsiraka and Marc Ravalomanana paralyzed the nation for months until the military again intervened—this time to back Ravalomanana, whose pro-business policies revived growth but widened inequality.

The 2009 Coup and Prolonged Transition (2009–2013)

When Ravalomanana’s popularity waned, opposition leader Andry Rajoelina, then mayor of Antananarivo, led protests backed by elements of the armed forces. The 2009 coup ushered in nearly five years of suspension from the African Union and crippling aid cuts.

Civilian Return and Renewed Fracture (2013–2025)

Elections in 2013 brought Hery Rajaonarimampianina to power, followed by Rajoelina’s return in 2018. Despite modest economic gains, corruption, weak infrastructure, and power shortages persisted.

By 2023, democratic fatigue was evident: turnout plunged, opposition parties boycotted, and urban frustration boiled over.

In 2025, the CAPSAT mutiny and street protests merged into a decisive rupture. Parliament impeached Rajoelina, the president fled, and Col. Michael Randrianirina declared a transitional government—Madagascar’s sixth regime change in sixty years.

3 | Current Political Situation (October 2025)

- Presidency: Vacant; Rajoelina reportedly in exile.

- Military: CAPSAT commands all branches and central administration.

- Parliament: The National Assembly remains formally seated but powerless.

- Judiciary: Courts and commissions suspended “pending reform.”

- Transition Plan: Elections and a constitutional referendum promised within two years, though no binding schedule is in place.

4 | Economic and Trade Profile

Madagascar’s economy remains fragile and highly export-dependent.

Key products include nickel and cobalt (≈ USD 800 million annually), vanilla (≈ USD 389 million), cloves (≈ USD 340 million), gold (≈ USD 250 million), and textiles (≈ USD 170 million).

Exports flow mainly to China, India, Oman, France, and South Africa; imports come chiefly from China, Oman, France, India, and the UAE.

Major industrial anchors:

- Ambatovy Nickel/Cobalt Mine (Sumitomo-led consortium).

- QMM Ilmenite Mine (Rio Tinto joint venture).

5 | Education and Income

Adult literacy stands near 78 percent, while learning poverty—children unable to read by age 10—remains around 94 percent. Primary completion rates are roughly 57 percent for boys and 62 percent for girls.

The World Bank classifies Madagascar as Low-Income, with Gross National Income (GNI) per capita below USD 1,135 and nominal GDP per capita around USD 600.

6 | Defense and Security Forces

The defense establishment consists of an Army, Navy, Air Force, and internal Gendarmerie/Police.

The Army dominates politics and internal order.

The Navy’s few patrol vessels operate from Antsiranana, Nosy Be, and Mahajanga, policing the channel for illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing.

The Air Force possesses light transports and helicopters but minimal combat aircraft.

Foreign training and equipment arrive intermittently from France, the United States, and China.

7 | External Actors and Influence

- France remains the legacy power, leveraging its territories in Réunion and Mayotte for military reach and EU diplomacy.

- India, through its SAGAR (4) initiative, expands radar networks and port calls to secure Indian Ocean shipping.

- China deepens ties via the BRI (2) and may exploit economic distress to gain long-term concessions.

- Japan and South Korea safeguard their stakes in Ambatovy and could offer technical aid.

- The United States focuses on maritime security, critical-mineral supply chains, and democratic governance.

Expect intensifying competition among France, India, and China over influence and access during the transition.

8 | Possible Futures (2025 – 2027)

Credible Transition:

A published election calendar, reopened courts, and donor engagement restore legitimacy. Exports stabilize, investment resumes, and tourism revives.

Managed Stagnation:

Delays and selective repression persist under a veneer of reform. Economic uncertainty and youth emigration rise.

Entrenchment or Fragmentation:

The junta hardens or fractures; AU/SADC (8) sanctions follow. Exports falter, humanitarian stress deepens, and external authoritarian actors gain ground.

9 | Policy Risks and Opportunities (U.S. Perspective)

Strategic Risks

- Resource Nationalism and Contract Risk

The transitional regime may reopen or revoke agreements for Ambatovy, QMM, and smaller mining concessions. Western firms could face retroactive taxation or forced joint ventures, particularly if China offers bail-out financing. - Democratic Backsliding and Human Rights Concerns

Prolonged military rule risks entrenching authoritarian practices. Crackdowns on journalists and civil-society groups would isolate the country from donors and could trigger AU or U.S. sanctions. - Migration and Humanitarian Pressure

Political uncertainty and climate stress (cyclones, droughts) could push thousands toward Comoros, Réunion, and Mozambique, straining regional capacities and humanitarian budgets. - Geopolitical Drift to Authoritarian Patrons

Should Western aid pause, the junta may pivot toward Chinese or Russian security partners, trading resource access for political backing. - Maritime Insecurity

A weakened or politicized navy would hamper anti-IUU enforcement and open the channel to trafficking and piracy, threatening commercial shipping and U.S. maritime interests.

Opportunities for Constructive Engagement

- Governance Conditionality

Tie all financial support to a transparent, dated transition roadmap endorsed by the African Union (AU) and Southern African Development Community (SADC). - Maritime Partnerships

Expand Maritime Domain Awareness cooperation, providing small-craft support, radar integration, and training to curb illegal fishing and improve search-and-rescue readiness. - Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief (HADR) (5)

Cyclone-response and climate-resilience projects build goodwill and protect U.S. brand presence without direct political entanglement. - Economic Resilience and Supply-Chain Diversification

Convene U.S. buyers of vanilla and critical minerals to design contingency sourcing and fair-trade initiatives, insulating American firms from price spikes while supporting Malagasy producers. - Multilateral Coordination

Align with EU, France, India, and Japan to deliver a unified donor message. Coordinated diplomacy reduces space for opaque deals under the BRI and promotes transparent resource governance.

10 | Key Facts at a Glance

- Population: ≈ 31 million (2025 est.)

- Income Level: Low-income economy (GNI ≤ USD 1,135)

- Adult Literacy: ≈ 78 %

- GDP per Capita: ≈ USD 600 (nominal)

- Main Exports: Nickel, Vanilla, Cloves, Gold, Textiles

- Primary Partners: China, Oman, India, France, South Africa

- Defense Branches: Army, Navy, Air Force, Gendarmerie, Police

Footnotes – Acronyms and Terms

- CAPSAT — Corps of Personnel, Administrative, and Technical Services (elite Malagasy military unit).

- BRI — Belt and Road Initiative, China’s global infrastructure and finance program.

- IUU Fishing — Illegal, Unreported, and Unregulated fishing activities.

- SAGAR — Security and Growth for All in the Region, India’s Indian Ocean policy framework.

- HADR — Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief, disaster-response cooperation.

- GNI — Gross National Income, used for World Bank income classification.

- WB / IMF / EU — World Bank, International Monetary Fund, European Union.

- AU / SADC — African Union and Southern African Development Community, regional bodies for governance and security.

- USD — United States Dollar.