A collaboration between Lewis McLain & AI

I. The Altar — Meeting Place Between Heaven and Earth

From the earliest days of faith, the altar has been humanity’s meeting place with God. In Genesis, Noah built one in gratitude; Abraham laid his hopes upon one in obedience; and Jacob called his altar Bethel — “the house of God.” The altar marks the intersection of the divine and the human, the eternal and the ordinary.

In every age and every church, the altar still stands as a sacred center. Whether made of stone or wood, draped in linen or simply polished by years of prayer, it represents holy ground — a place of confession, covenant, and communion.

It is the heartbeat of the church: where infants are dedicated, believers are baptized, couples are joined, missionaries are sent, sinners are forgiven, and the saints are remembered. At its center lies one invitation that transcends time and tradition: “Come.”

II. The Altar of Beginning — Baptism and Dedication

“Just as I am, without one plea,

But that Thy blood was shed for me,

And that Thou bidd’st me come to Thee,

O Lamb of God, I come, I come.”

The first encounter many have with the altar comes at baptism — a moment of beginning and belonging. In some traditions, parents carry infants forward, dedicating them to God’s care. In others, such as Baptist and evangelical churches, baptism comes later, when faith has taken root and understanding has matured.

Young believers often attend classes to grasp the meaning of their decision — to understand repentance, forgiveness, and the public declaration of faith. Then, before family and congregation, they descend into the waters of baptism by immersion, a visible sign of dying to the old life and rising to newness in Christ.

The placement of the baptistry — often elevated behind or above the altar — reminds the congregation that baptism is central to the Christian life. It is both testimony and transformation. The water may shimmer under bright lights, but the moment itself is profoundly intimate: the old self buried, the new self raised, both embraced by the same grace that whispers, “Come to Me.”

III. The Altar of Union — Marriage and Covenant

“Just as I am, though tossed about

With many a conflict, many a doubt,

Fightings and fears within, without,

O Lamb of God, I come, I come.”

Years later, the same altar bears witness to another kind of covenant. A couple stands before it, hands trembling, hearts steady. They exchange vows — not promises of perfection but of perseverance, pledging to walk together through the “fightings and fears” within and without.

The altar is both witness and anchor. Here, love becomes covenant — sealed not by emotion alone, but by the presence of God. The congregation watches as two lives intertwine in divine partnership, bound by grace. Long after the music fades and the flowers wilt, the altar will still “remember.” Every Christian marriage, no matter how strong or tested, stands upon that moment of surrender — not to one another’s will, but to God’s sustaining love.

IV. The Altar of Communion — The Table of Remembrance

“Just as I am, poor, wretched, blind;

Sight, riches, healing of the mind;

Yea, all I need in Thee to find,

O Lamb of God, I come, I come.”

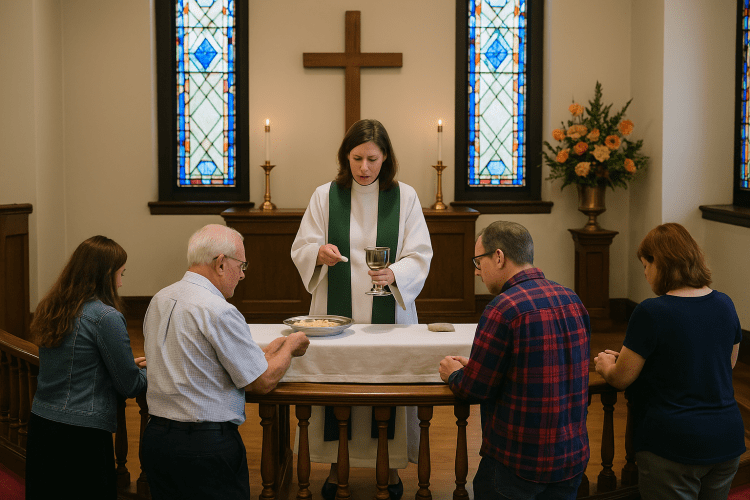

Between the milestones of life, believers return again and again to the altar for communion — the Lord’s Supper, the Eucharist, the breaking of bread.

This regular return to the altar renews the heart and re-centers the soul. The table is not merely ritual; it is relationship. It is where the church remembers the sacrifice that makes every other altar moment possible. The bread and cup are tangible grace — reminders that Christ’s body and blood were given not for the perfect, but for those who come “poor, wretched, blind.”

Communion teaches us that every approach to the altar — for baptism, marriage, confession, or mission — begins with gratitude for the One who first invited us. “Do this in remembrance of Me,” Jesus said, not as a command to repeat, but as a call to return — again and again, just as we are.

V. The Altar of Calling — Mission and Sending

“Just as I am, Thou wilt receive,

Wilt welcome, pardon, cleanse, relieve;

Because Thy promise I believe,

O Lamb of God, I come, I come.”

For some, the altar becomes a launching place — a threshold to mission. Here pastors are ordained, missionaries commissioned, and disciples sent forth to proclaim the gospel.

When Billy Graham preached, his altar calls were not only for conversion but for commission. His voice carried across stadiums, yet his invitation was profoundly personal: “You come, just as you are.” As the hymn filled the air, the aisles filled with people — young and old, doubting and desperate — each one trusting the promise: “Thou wilt receive.”

Many came to Christ for the first time; others came to give their lives to service — to teach, to heal, to go. The altar here becomes both an end and a beginning — the surrender of will, the start of purpose. It is the place where “Here am I, Lord” becomes more than words; it becomes life’s direction.

VI. The Altar of Surrender — The Call to Salvation

The heart of the altar experience is the call to salvation — the moment when pride yields, sin confesses, and grace embraces.

In churches large and small, the invitation is still given. The choir begins softly, the congregation prays silently, and the Spirit stirs unseen. One by one, hearts move before feet do. Then someone steps forward — the longest and shortest walk of a lifetime.

Billy Graham called it “the hour of decision.” The act of coming forward is not magic; it is movement — an outward sign of inward faith. It says, “I am done hiding. I need Jesus.”

This is the altar’s central truth: it is not the location that saves, but the Lord who meets us there. Yet that simple act of obedience — rising, walking, coming — has carried countless souls across the threshold of eternity.

VII. The Altar of Farewell — Funerals and Resurrection Hope

“Just as I am — Thy love unknown

Hath broken every barrier down;

Now to be Thine, yea, Thine alone,

O Lamb of God, I come, I come.”

Even at life’s final chapter, the altar remains the meeting place. Before it, families gather in grief and gratitude. The same altar that saw baptism’s joy and marriage’s promise now bears the weight of loss — yet not despair.

For believers, the funeral is not a farewell of defeat but of fulfillment. The love unknown that “breaks every barrier down” has already conquered death. The altar reminds us that every life lived in Christ ends not in darkness but in dawn. The one who once walked forward trembling now walks into glory with confidence, still saying, “I come.”

VIII. The Altar Eternal — The Invitation That Never Ends

Across centuries, the altar has remained constant — not as furniture, but as symbol. It calls us at every age and stage of life:

- At birth, to be dedicated.

- In youth, to be baptized.

- In union, to be joined.

- In mission, to be sent.

- In communion, to be renewed.

- In salvation, to be redeemed.

- In death, to be received.

Every time we come, the invitation echoes: “Just as I am.”

The altar is not only a place in church — it is a rhythm of grace, a lifelong call to approach God honestly, humbly, and repeatedly. We never stop coming, and He never stops receiving.

So whether it is water or bread, a vow or a farewell, the altar stands — a reminder that God’s love meets us not when we are ready, but when we respond.

O Lamb of God, I come. I come.

Epilogue: The Altar That Never Closes

The altar is not just a place we visit — it is the shape of the Christian life. Every beginning, vow, calling, and farewell echoes one continuing invitation: “Come.”

In Scripture, the altar appears wherever God meets His people — in wilderness and temple, on mountaintops and upper rooms, in the heart of one who prays. The church altar stands as a symbol of that meeting, but the truth it proclaims reaches beyond its rail and candles. The altar, in the end, is wherever Christ reigns and the human heart responds.

The Altar of Daily Surrender

“If anyone would come after Me, let him deny himself and take up his cross daily and follow Me.” — Luke 9:23

Every morning, long before the church doors open, there are altars unseen — the kitchen table where a believer opens the Word, the quiet car before the day begins, the walk under sunrise whispered with prayer.

This altar of daily surrender is not lit by candles but by conviction. It is where worship leaves the sanctuary and enters the schedule. The posture is the same: bowed head, open hands, honest heart. In that stillness, grace meets routine and holiness becomes ordinary.

The Altar in the Home

“Impress these words on your children. Talk about them when you sit at home and when you walk along the road.” — Deuteronomy 6:7

Every home that prays together becomes a little church. The family table becomes an altar when bread is broken with gratitude. The living room becomes holy ground when Scripture is read aloud.

Faith is not preserved by programs but by presence — by seeing faith lived out in daily rhythm. Children learn to love the God their parents trust. At the altar of the home, worship is taught not in words alone, but in tone, laughter, forgiveness, and everyday grace.

The Altar in the World

“Whatever you did for one of the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did for Me.” — Matthew 25:40

When the faithful leave the church, the altar travels with them. The teacher’s desk, the hospital room, the job site, the homeless shelter — all can become altars when compassion and justice are offered in Christ’s name.

Here, worship becomes action. The same hands that once received the bread now extend it to the hungry. The same feet that once walked forward to the altar now go forward to serve. Every believer becomes a living sacrament — carrying God’s presence into places the sanctuary light cannot reach.

The Empty Altar — Heaven’s Completion

“Now the dwelling of God is with men, and He will live with them.” — Revelation 21:3

At last the altar stands empty, radiant, waiting. The candles are no longer needed, for the Lamb Himself is the light. Those who once knelt before the rail now stand before the throne, singing “Just As I Am” not as a plea, but as praise fulfilled.

No more coming forward — only abiding forever. The journey that began in water and bread ends in glory and grace.

Appendix A: The Story Behind “Just As I Am”

Charlotte Elliott (1789–1871): The Voice of Honest Faith

Charlotte Elliott was born in Clapham, England, into a devout but intellectually refined family. Her grandfather was a close friend of the hymnwriter Isaac Watts, and her brother, the Rev. H.V. Elliott, became a well-known clergyman and educator.

Charlotte herself was a gifted poet and musician, but her life was marked by chronic illness that left her bedridden for long seasons. In her youth, she wrestled deeply with doubt about her faith. She feared she was unworthy of God’s love — that her weakness and uncertainty disqualified her from salvation. When Rev. César Malan of Geneva asked if she knew Christ personally, she replied that she didn’t know how to come to Him. His answer pierced her heart:

“Come to Him just as you are.”

Years later, in 1835, still struggling with infirmity but clinging to grace, Charlotte wrote the words that would echo through generations:

“Just as I am, without one plea,

But that Thy blood was shed for me…”

The hymn appeared in The Christian Remembrancer that year and was later included in her collection The Invalid’s Hymn Book.

Though confined by illness, Charlotte Elliott’s simple honesty created one of Christianity’s most universal hymns — a melody of mercy that has carried millions to the altar of grace.

William B. Bradbury (1816–1868): The Tune of Invitation

The tune most commonly associated with “Just As I Am” was composed by William Batchelder Bradbury in 1849. Bradbury, known for “Jesus Loves Me” and “Sweet Hour of Prayer,” wrote a melody that moves with the same steady rhythm as the walk to the altar — step by step, forward, sincere.

Together, Elliott’s words and Bradbury’s music became the sound of surrender, humility, and homecoming.

Appendix B: Hymnic Lineage and Influence

Charlotte Elliott’s hymn “Just As I Am” arose from the same devotional stream as Isaac Watts (1674–1748), the father of English hymnody.

Like Watts, she believed hymns should be personal and Scriptural — carrying doctrine into daily devotion and prayer.

Isaac Watts’ Hymns That Shaped Her Era:

- “When I Survey the Wondrous Cross”

- “Joy to the World”

- “O God, Our Help in Ages Past”

Her work stands as a continuation of that lineage: theology sung through human honesty — heaven’s truth whispered in earthly weakness.