A collaboration between Lewis McLain & AI

Economics is about more than charts and numbers. At its core, it is about how people live: whether they are free, whether they are secure, and whether they can provide for themselves and their families. Over the centuries, two broad traditions have defined the debate. The free-market thinkers argue that liberty, incentives, and voluntary exchange are the best engines of prosperity. The interventionist thinkers argue that government must step in to correct markets, protect the vulnerable, and guide society toward fairness. Both traditions arose in response to real crises and genuine human needs, but their answers could not be more different.

🟢 Adam Smith (1723–1790): The Founder of Modern Economics

Every discussion of markets must begin with Adam Smith, the Scottish philosopher who wrote The Wealth of Nations in 1776. Smith described the economy as guided by an “invisible hand”: when individuals pursue their own self-interest, they unintentionally create benefits for others. His famous example was the butcher, the brewer, and the baker, who do not provide dinner out of kindness but out of a desire to earn a living. Yet the result is food on every table.

For Smith, prosperity did not require kings, parliaments, or central planners to decide what people should have. The natural coordination of supply and demand through prices did the job. But Smith was not only an economist of self-interest. In his earlier book, The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759), he stressed the importance of virtue, ethics, and sympathy for others. Together, these works made him both the father of economics and an advocate of responsibility.

Smith’s vision anchors the debate: are markets left to themselves enough, or must governments take a stronger role? He also provides a bridge to the modern theme of self-sufficiency: when individuals and families take responsibility for their own choices, the entire society becomes more resilient.

The Free-Market Thinkers

🟢 Milton Friedman (1912–2006)

Milton Friedman grew up poor in Brooklyn and rose through scholarships to become the most famous champion of free markets in 20th-century America. Unlike Rothbard, he did not reject government entirely. Friedman believed the state should protect property, enforce contracts, and perhaps provide a minimal “safety net.” But he fiercely opposed most welfare programs, which he argued trapped people in dependency.

He saw money as the key to economic stability, famously stating, “Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.” He blamed the Federal Reserve for deepening the Great Depression by failing to stabilize the money supply. His reforms included the negative income tax (a simpler form of welfare) and school vouchers to expand parental choice. For Friedman, freedom came first, and prosperity followed.

🟢 Friedrich Hayek (1899–1992)

Friedrich Hayek lived through the collapse of Austria-Hungary, World War I, and the rise of fascism and communism. These experiences convinced him that liberty was fragile. In The Road to Serfdom (1944), he warned that central planning, even if motivated by compassion, would inevitably erode freedom.

Hayek’s core idea was that knowledge in society is dispersed. No central planner could ever gather enough information to direct the economy better than markets could. Prices act as signals, coordinating millions of choices without coercion. His philosophy was cautionary: liberty must be preserved by keeping governments from overreaching.

🟢 Murray Rothbard (1926–1995)

Murray Rothbard took Hayek’s and Friedman’s skepticism to its furthest conclusion. He believed government itself was illegitimate because it rested on coercion. In his system of anarcho-capitalism, even courts, police, and national defense would be privatized. Rothbard’s famous declaration was blunt: “The state is a gang of thieves writ large.”

Where Friedman accepted a minimal state and Hayek warned against overreach, Rothbard rejected the state altogether. His ideas remain controversial, but they highlight the radical edge of free-market thought.

🟢 Thomas Sowell (1930– )

Thomas Sowell’s journey took him from Harlem poverty to the Marine Corps to Harvard and the University of Chicago. Early in life he was a Marxist, but after working inside government he came to believe that state programs failed ordinary people. Sowell’s lifelong emphasis is on incentives and unintended consequences.

He argued that welfare often undermined family stability and personal responsibility. He showed how culture and history often explain group disparities better than discrimination alone. His warning was simple: “There are no solutions. There are only trade-offs.” Like Smith, Sowell tied economics to human character — a reminder that prosperity depends on responsibility, discipline, and self-sufficiency.

The Interventionist Thinkers

🔴 John Maynard Keynes (1883–1946)

John Maynard Keynes transformed economics during the Great Depression. He was not a socialist — he defended markets — but he argued that markets could stagnate during prolonged periods of unemployment. His solution was for the government to borrow and spend during downturns, creating jobs and restarting demand, and then to cut back when prosperity returned.

Keynes’s legacy was saving capitalism from collapse by making government the “manager” of the economy. Where Smith’s invisible hand trusted individual choices, Keynes’s hand of policy was visible, intentional, and deliberate.

🔴 John Kenneth Galbraith (1908–2006)

Galbraith, the Canadian-born Harvard professor, argued that mid-20th-century America suffered from “private affluence and public squalor.” People bought luxury cars and televisions while schools, infrastructure, and parks decayed. He believed advertising distorted free choice and that corporations bent markets to their will. His solution was more government investment in public goods. For Galbraith, true prosperity was measured not by what a few could buy but by what all could share.

🔴 Gunnar Myrdal (1898–1987)

The Swedish economist Gunnar Myrdal co-designed his nation’s welfare state. He believed that poverty and discrimination would not solve themselves through markets. Instead, the government had a moral duty to redistribute wealth and engineer equality. His book An American Dilemma (1944) influenced U.S. civil rights debates, highlighting the gap between American ideals and racial realities. For Myrdal, equality did not naturally emerge; it had to be created intentionally.

🔴 Paul Samuelson (1915–2009)

Paul Samuelson, the first American Nobel laureate, popularized Keynesian economics in the classroom through his textbook. He treated government stabilization policies as routine and necessary. Samuelson believed experts could “fine-tune” the economy to prevent recessions and smooth growth. He represented the mainstreaming of Keynesian ideas — turning temporary crisis measures into long-term expectations.

🔴 Joseph Stiglitz (1943– )

Joseph Stiglitz expanded the interventionist case by focusing on information asymmetry: the idea that one side in a deal often knows more than the other, leading to unfairness and collapse. He criticized deregulation and globalization for creating fragile systems that benefit elites while harming ordinary people. His prescription was more regulation, more redistribution, and more protection for the vulnerable. For Stiglitz, government is the referee that keeps capitalism fair.

🔴 Thomas Piketty (1971– )

Thomas Piketty reignited debate in the 21st century with Capital in the 21st Century (2013). He argued that capitalism naturally concentrates wealth because returns on capital grow faster than the economy overall. Without strong taxation, societies drift into oligarchy — rule by the rich. His solution is progressive taxation to preserve democracy. Where Smith saw self-interest fueling growth, Piketty saw it endangering equality.

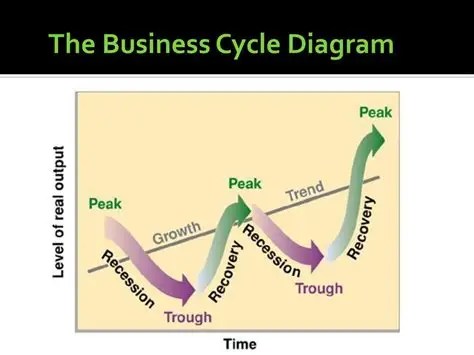

The Natural Economic Cycle

Beyond individual policies, every economy moves through a natural cycle of growth and decline, often called the business cycle. This rhythm is tied to supply and demand and to the approach of full employment — the point where nearly all who want work can find it. During expansions, demand rises, businesses hire, and unemployment falls. As labor becomes scarce, wages and prices climb. Eventually the economy reaches a peak, where inflationary pressures grow. Then comes contraction: demand slows, businesses cut back, and unemployment rises. After the trough, recovery begins, and the cycle starts again.

This pattern is so consistent that economists chart it visually:

Phases of the Cycle:

- Expansion: Rising demand, hiring, falling unemployment.

- Peak: Economy near full employment, inflation pressures appear.

- Contraction: Falling demand, layoffs, rising unemployment.

- Trough: Output bottoms, unemployment high.

- Recovery: Demand rebounds, cycle begins anew.

If this cycle is natural, the question arises: why do governments and central banks try to smooth it out?

Reasons for Intervention

- Pain Avoidance: Recessions bring high unemployment, bankruptcies, and hardship. Leaders intervene to limit suffering.

- Political Pressure: Voters punish politicians during downturns, so governments act to “do something.”

- Belief in Expertise: Keynesians argue trained policymakers can shorten recessions and prevent depressions.

- Fear of Instability: In a global economy, one nation’s crash can ripple worldwide, so intervention is seen as necessary to avoid collapse.

The Debate

- 🔴 Interventionists (Keynes, Samuelson, Stiglitz, Piketty) argue that the human costs of long downturns are too great to leave to chance.

- 🟢 Free-marketers (Friedman, Hayek, Sowell, Rothbard) argue that interventions often cause worse long-term problems: inflation, debt, or dependency.

Thus, the cycle itself is not disputed — the argument is whether we should ride it out naturally or manipulate it in hopes of softening the blows.

The Federal Reserve: The Great Divide

The Federal Reserve, America’s central bank created in 1913, became the lightning rod of the market vs. government debate.

- 🟢 Free-market thinkers distrusted it. Friedman wanted it constrained by strict rules. Hayek preferred competing currencies. Rothbard wanted it abolished. Sowell criticized its repeated failures.

- 🔴 Interventionist thinkers embraced it. Keynes saw it as a tool to fight recessions. Galbraith welcomed its power to balance corporations. Myrdal and Samuelson treated it as essential to the welfare state. Stiglitz wanted it reformed to fight inequality. Piketty viewed it as necessary but secondary to taxation.

Originally, the Fed’s role was mostly about banks and money. But in 1946, the Employment Act committed the government to pursue “maximum employment.” Later, the Humphrey-Hawkins Act of 1978 gave the Fed a dual mandate: keep prices stable and promote jobs. This sounds straightforward, but it creates a constant tension. Raising interest rates to control inflation often hurts jobs. Lowering rates to help jobs can fuel inflation. That impossible balancing act lies at the heart of the disagreement: should we trust markets or experts to steer the economy?

Self-Sufficiency: From Nations to Individuals

The deeper thread running through these debates is self-sufficiency. For Adam Smith, prosperity began when individuals pursued their own interests with prudence. For Friedman and Sowell, welfare failed because it weakened personal responsibility. For Hayek, liberty was preserved only when people managed their own affairs.

Self-sufficiency applies to nations as well. A country that can feed itself, produce its own energy, and defend itself is less vulnerable to outside shocks. The oil crises of the 1970s, for example, showed the dangers of dependency.

It also applies to individuals. Families that budget, save, and live within their means are more resilient in recessions. Workers who develop new skills stay employable as economies change. Communities with strong networks — churches, civic groups, neighbors — provide help before government needs to intervene. Self-sufficiency is not isolation; it is resilience. It reduces dependency, strengthens freedom, and makes prosperity sustainable.

Conclusion

From Smith’s Invisible Hand to Piketty’s warnings about inequality, the debate between free markets and government intervention has shaped the modern world. Both sides offer lessons. Keynes was right that governments must sometimes step in during crises. Stiglitz is right that markets sometimes fail. But history shows that free markets, anchored in liberty and strengthened by self-sufficiency, remain the surest path to prosperity.

The best model is a society where markets drive innovation, government remains lean but capable in emergencies, and individuals and families live with discipline and resilience. Such a society protects freedom, sustains prosperity, and ensures that liberty is not fragile — because it rests on self-sufficient people who can stand tall and contribute to the common good. Economic education is not just for college professors. Individuals must grasp the basics, be a willing participant, and contribute a variety of tolerance and defensive skills.

Key Terms Explained (Alphabetical Order)

- Affluent Society: 🔴 John Kenneth Galbraith’s concept (1958) that modern capitalism can produce “private affluence and public squalor” — abundant consumer goods alongside neglected public services.

- Anarcho-Capitalism: 🟢 Murray Rothbard’s radical vision where even courts, police, and defense are privatized; government is eliminated entirely.

- Central Planning: When government authorities, not markets, decide what to produce, how to allocate resources, and at what price. Associated with the Soviet Union’s command economy.

- Dual Mandate of the Fed: Since the Employment Act of 1946 and the Humphrey–Hawkins Act of 1978, the Federal Reserve has been tasked with two goals: price stability (low inflation) and maximum employment (jobs). These can conflict — fighting inflation may reduce jobs, and boosting jobs may raise inflation.

- Free Market: An economy where prices and production are set by voluntary exchange between buyers and sellers with minimal government involvement.

- Incentives: Rewards or punishments that influence behavior. Example: higher wages encourage more work, while overly generous benefits may discourage it.

- Information Asymmetry: When one side in an exchange has more knowledge than the other (e.g., a seller knowing more than the buyer). 🔴 Joseph Stiglitz used this idea to argue for regulation.

- Monetarism: 🟢 Milton Friedman’s view that controlling the money supply is the key to controlling inflation and stabilizing the economy.

- Oligarchy: A system where a small group of wealthy elites dominate society and politics. 🔴 Thomas Piketty warned that unchecked capitalism tends toward oligarchy.

- Redistribution: The transfer of wealth from one group to another through taxation and welfare programs. Supported by 🔴 Myrdal, 🔴 Stiglitz, and 🔴 Piketty.

- Safety Net: A set of government programs designed to protect people from extreme poverty, such as unemployment benefits, food stamps, or basic healthcare. Accepted by 🟢 Friedman in lean form.

- Stagflation: A situation where the economy experiences both high inflation and high unemployment, as in the U.S. during the 1970s. It challenged Keynesian economics.

- Unintended Consequences: Unexpected effects of policies, often harmful. Example: rent control lowers rents for some but reduces overall housing supply. A central theme of 🟢 Thomas Sowell.

- Welfare State: A government system that provides broad social benefits — pensions, healthcare, unemployment aid — funded by taxation. Strongly defended by 🔴 Myrdal and 🔴 Galbraith.