A collaboration between Lewis McLain & AI

Introduction: A Book of Its Moment and Ours

Why have I, Lewis McLain, spent my career in municipal government? What was it that drew me to the public sector? A big part of my choice is directly attributed to this book. After one year in a branch of a big private sector company (Boise Cascade), where promotions meant moving, I knew I wasn’t ready for the sacrifice. I remember people jokingly saying that IBM is short for “I’ve been moved!” Then I read Toffler’s book. It scared the heck out of me. I sought a job with the City of Garland, where we lived at the time. Cities don’t have branches! LFM

Published in 1970, Alvin Toffler’s Future Shock was one of the most influential books of its generation. Toffler, a journalist turned futurist, gave words to an emerging unease: life was speeding up, choices were multiplying, and technology was accelerating change faster than people could adjust. His phrase “future shock” entered the lexicon to describe the psychological disorientation produced by “too much change in too short a period of time.” Much like a traveler overwhelmed by jet lag, whole societies were beginning to feel a kind of “time sickness.”

The book was not a narrow technological manual but a sweeping cultural diagnosis. Toffler’s aim was to alert readers that the accelerating pace of life, driven by computers, automation, new forms of media, and global connectivity, would alter not only how we work but how we think, love, and build communities.

Alvin Toffler: A Brief Biography

Alvin Toffler (1928–2016) was born in New York City and grew up in a working-class family. After studying English at New York University, he worked as a laborer and welder before becoming a journalist. Those early years in industry gave him a firsthand view of the transformation of work and technology. Later, as a writer for publications such as Fortune, he began to explore the social and cultural impact of science and industry.

Toffler’s career blended journalism, research, and futurism. Together with his wife and intellectual partner Heidi Toffler, he developed a series of influential books—Future Shock (1970), The Third Wave (1980), and Powershift (1990)—that examined the accelerating changes of modern society. Known for his sweeping predictions and cultural diagnoses, he became one of the most widely read futurists of the 20th century. His work was translated into dozens of languages and influenced policymakers, business leaders, and educators across the globe.

Why Toffler Wrote the Book

Toffler wrote Future Shock because he sensed a growing mismatch between human adaptability and technological progress. He had worked in factories and later as a researcher at IBM, where he saw firsthand how automation was transforming industry. He and his wife, Heidi, realized that while institutions and technologies were racing ahead, human beings were still wired for slower, steadier rhythms of life.

In his own words, “Man has a limited biological capacity for change. When this capacity is overwhelmed, the capacity is in future shock.” His mission was both descriptive and prescriptive: to describe what was happening, and to warn that societies must learn “future consciousness” to survive.

Core Principles and Examples

One of the most important principles in Future Shock is Toffler’s idea of the acceleration of change. He noted that while in earlier centuries a new invention or a new trade might take generations to spread, by 1970 the cycle of change had compressed dramatically. Technologies were appearing and disappearing within a single lifetime, creating disorientation. He used examples such as careers that no longer lasted a lifetime and marriages that no longer endured in the same way as before. Today, the constant churn of smartphone models, rapid software updates, and the rise of gig-work platforms confirm his observation that technological and social change move faster than human beings can comfortably absorb.

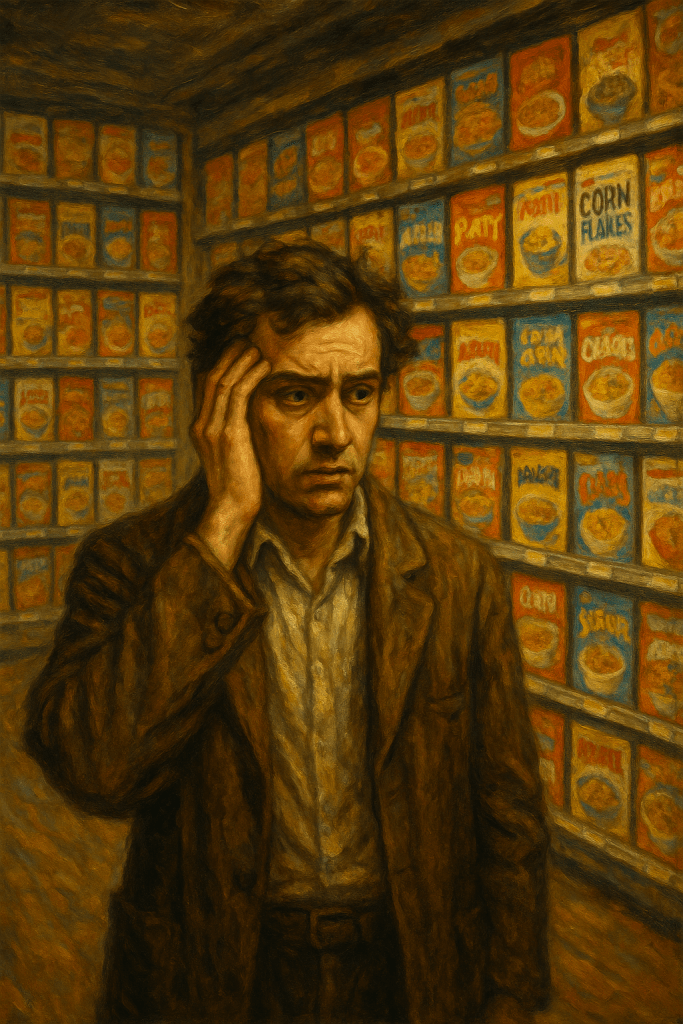

Another theme in the book is what Toffler called “overchoice.” He observed that supermarkets, which once carried just a handful of cereals, were beginning to display dozens of varieties. He argued that such abundance, far from liberating people, often left them paralyzed by indecision. In modern times, we see the same phenomenon in streaming services with their endless libraries, in online dating platforms where swiping can feel overwhelming, and in online marketplaces where too many options make decision-making difficult. Choice itself can become a source of stress.

Toffler also warned about the rise of what he called the “disposable society.” This was not simply about throwaway plastic cups or paper plates, though he noted those as signs. It was also about a mentality of disposability—relationships, careers, and even values that could be cast aside when they no longer seemed convenient. Fast fashion, job-hopping, and the casual end of personal ties in the digital age show that this disposability has expanded beyond what Toffler imagined.

A further insight was Toffler’s concept of “modular man.” He believed people would increasingly live modular lives, attaching and detaching themselves from jobs, communities, and identities with little permanence. Instead of being deeply rooted in one place or one community, individuals would assemble their lives like building blocks, changing them as circumstances shifted. In our own time, this is reflected in global mobility, fluid online identities, and the constant reinvention demanded by the modern labor market.

Finally, though developed more fully in his later work The Third Wave, Toffler hinted at what he called the “high-tech, high-touch” paradox. The faster technology advanced, the more people would seek grounding in intimate, human experiences. In other words, as life became digitized and accelerated, there would be a compensating hunger for touch, presence, and slower rhythms. This is echoed in today’s wellness culture, mindfulness movements, and digital detox practices, all of which point to a longing for balance in the midst of technological saturation.

Theological and Human Reflections

Although Future Shock is a secular work, it raises questions that touch on theology and human meaning. Communities of faith, for example, can help people resist the disorientation of accelerated change by offering stability, ritual, and timeless wisdom. The book invites reflection on whether virtues such as patience, faithfulness, and steadfastness might be even more critical in an age of flux. It also forces us to ask what balance is needed between embracing innovation and protecting the slow, deliberate work of relationships, worship, and contemplation.

Practical “What Now?” Guide

Toffler’s warnings are even more urgent today, and his book is not only descriptive but suggestive of how people might adapt. One practical response is to cultivate what he called “future consciousness.” This means developing awareness of trends without being enslaved to them, and preparing mentally for change so that it does not always arrive as a shock. Staying informed about developments in artificial intelligence, for example, is important not to chase every novelty but to anticipate how such innovations will affect our lives and relationships.

Another practice is to build anchors of stability. Families can preserve rituals such as shared meals. Communities of faith can preserve weekly worship. Individuals can establish rhythms such as journaling or walking. These acts may seem small, but they create continuity in a sea of change.

It is also important to curate choices deliberately. In a world that constantly multiplies options, simplicity is itself a discipline. People can unsubscribe from unnecessary information streams, set limits on consumption, and consciously define what truly matters. By narrowing the field of decision-making, they recover a sense of peace.

Toffler also challenges us to value durability in an age of disposability. This might mean investing in long-term commitments such as marriage, vocation, or community service, even when the cultural tide pulls toward transience. Such commitments may feel countercultural, but they are also deeply human.

Finally, balance is essential. For every hour spent online, one might dedicate an hour to embodied presence: walking with a friend, eating together, or praying quietly. Technology can expand horizons, but it cannot replace touch, silence, or love. In this way, people can ensure that “high-tech” is matched with “high-touch.”

Conclusion: The Prophecy Fulfilled

More than fifty years later, Future Shock feels less like a dated prophecy and more like a daily reality. Toffler’s words anticipated social media churn, rapid job disruption, the mental health crisis of overstimulation, and the dizzying pace of globalization. His essential message—that humans must consciously adapt to the speed of change without losing their humanity—remains a guidepost.

Just as Reuel Howe in The Miracle of Dialogue called us back to authentic encounter, Alvin Toffler in Future Shock calls us back to authentic stability. We cannot slow technology, but we can anchor ourselves, our families, and our communities to withstand the storm of acceleration.