A collaboration between Lewis McLain & AI

Introduction

Few books (if any) have shaped human history as profoundly as the Bible. Revered as sacred Scripture by Jews and Christians, and respected by other traditions, the Bible is at once an ancient library, a theological manifesto, a work of literature, and a source of personal devotion. For Christians in particular, it is not merely a record of human religious thought but the inspired Word of God — “God-breathed,” as the Apostle Paul put it (2 Timothy 3:16). Inspiration means that, while written by human authors in particular times and places, the Bible ultimately conveys the message and truth of God Himself.

Because of this conviction, believers affirm the Bible’s infallibility: that in all matters of faith and practice it speaks without error, reliably guiding humanity to God’s will and salvation. The trustworthiness of the Scriptures is supported not only by theological conviction but also by historical evidence. The remarkable preservation of manuscripts, such as the Dead Sea Scrolls (1), shows the consistency of the biblical text over centuries. Thousands of New Testament manuscripts, some dating to within a century of the originals, provide far more textual support than any other ancient work. Archeological discoveries — from the ruins of Jericho to the records of Babylonian kings — often corroborate biblical accounts. Prophecies fulfilled in history, such as Isaiah’s foretelling of the suffering servant or Micah’s prediction of Bethlehem as Messiah’s birthplace, lend further weight to the claim of divine inspiration.

Yet Christians also recognize that not every mystery of the Bible can be resolved by reason or evidence alone. Faith is required. The most faithful of believers often acknowledge that some questions belong to what they call the “Why Line” — matters that will only be fully understood when we reach Heaven. This humble acceptance of mystery underscores the conviction that the Bible is trustworthy even where human understanding reaches its limits.

Historical Foundations and Canon

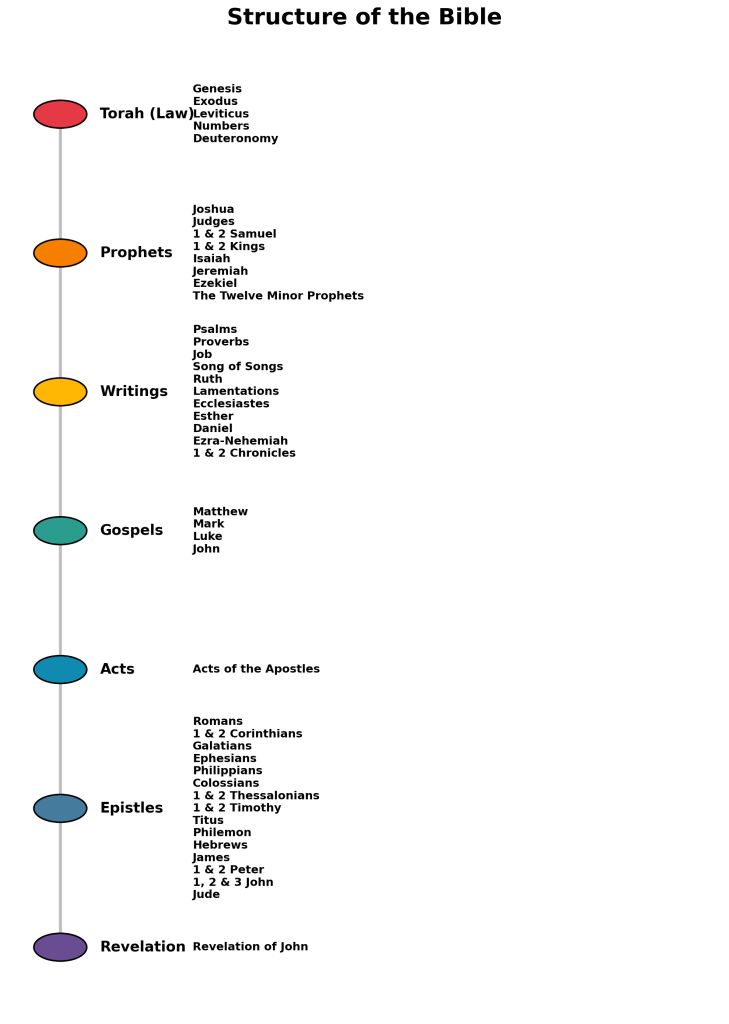

The Bible is best understood as a collection of sacred writings rather than a single book. Composed over some 1,500 years, it brings together voices as varied as shepherds and kings, prophets and priests, apostles and tentmakers. The Hebrew Bible, or Tanakh, is traditionally divided into three major sections: the Torah, the Prophets, and the Writings. Christians inherit this structure but order the books differently and add the New Testament, which consists of Gospels, Acts, Epistles, and Revelation.

The Torah provided the foundation for Jewish faith and practice, while the Prophets carried forward Israel’s story and interpreted it through the lens of God’s covenant demands. The Writings offered poetry, wisdom, and reflections for worship and daily living. Christians then recognized the Gospels as testimonies to the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus; Acts as the bridge between Jesus and the early church; the Epistles as letters of instruction; and Revelation as a vision of ultimate hope.

The recognition of these writings as authoritative was gradual, with Jewish communities closing their canon in the first centuries AD, and the Christian church largely confirming the New Testament canon by the fourth century. The very process of canonization (2) reveals how the community of faith shaped the Bible even as the Bible shaped the community. For believers, this process was guided not merely by human decision but by God’s providence, ensuring that the inspired Word was faithfully preserved for future generations.

The Hebrew Bible / Old Testament

The Torah, sometimes called the Pentateuch, includes Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy. These five books lay the theological foundation for everything that follows. Genesis introduces creation, humanity’s fall, and the beginnings of God’s covenant with Abraham. Exodus recounts Israel’s dramatic liberation from slavery and the giving of the Law at Sinai. Leviticus focuses on holiness, ritual, and the priestly system, while Numbers portrays Israel’s wilderness wanderings. Deuteronomy concludes the Torah by rehearsing the covenant and calling the nation to faithfulness before entering the promised land.

The Torah reveals God’s character as Creator, Redeemer, and Lawgiver, and its preservation through centuries testifies to its central role in Jewish and Christian faith. While skeptics debate details of chronology or authorship, believers affirm that God ensured the Torah’s message remained intact, even if some questions about its composition remain for the “Why Line.”

The Prophets are traditionally divided into the Former and the Latter Prophets. The Former Prophets — Joshua, Judges, Samuel, and Kings — recount Israel’s history from the conquest of Canaan to the Babylonian exile. These books are not merely chronicles of events; they interpret history through the lens of covenant obedience and disobedience.

The Latter Prophets include the “Major Prophets” — Isaiah, Jeremiah, and Ezekiel — as well as the “Minor Prophets,” the twelve shorter books from Hosea to Malachi. Isaiah brings a grand vision of judgment and restoration, Jeremiah warns of destruction yet promises a New Covenant, and Ezekiel combines vivid symbolic acts with hope for renewal.

This “New Covenant,” first announced in Jeremiah 31:31–34, promised that God would write His law not on tablets of stone but on the hearts of His people. Unlike the old covenant, which Israel repeatedly broke, the New Covenant would be marked by forgiveness of sins, an intimate knowledge of God, and a transformed inner life. Jesus later defined its essence when He declared that all the Law and the Prophets rest on two commandments: to love God with all one’s heart, soul, and mind, and to love one’s neighbor as oneself (Matthew 22:37–40). In this way, the New Covenant is both fulfillment and simplification — distilling the law’s deepest intent into love for God and love for others, made possible through the transforming power of the Holy Spirit.

The Writings form a diverse collection that includes poetry, wisdom, and historical reflection. Psalms gathers prayers and songs that span the full range of human emotion, from despair to jubilation. Proverbs offers compact sayings of wisdom for daily living, while Ecclesiastes reflects on the meaning of life in the face of mortality. Job wrestles with suffering and divine justice — a book that especially challenges human understanding, where many Christians confess that only eternity will fully reveal God’s purposes.

Other writings, like Ruth and Esther, tell stories of ordinary faithfulness and courage in extraordinary times. Lamentations mourns the destruction of Jerusalem, while Daniel combines narratives of exile with visions of God’s sovereignty. Chronicles and Ezra-Nehemiah retell Israel’s story with an eye toward restoration after exile. Together, the Writings remind readers that faith involves trust in God’s wisdom even when the reasons behind life’s trials are hidden.

The Judeo-Christian Heritage

The close relationship between the Old and New Testaments explains why many speak of the “Judeo-Christian” tradition. Christianity is deeply rooted in the faith of Israel. The moral law of the Torah, the prayers of the Psalms, and the prophetic hope of redemption all form the groundwork upon which Christianity is built.

Jesus himself was a Jew who affirmed the authority of the Hebrew Scriptures and declared that He came not to abolish the Law or the Prophets but to fulfill them (Matthew 5:17). The early church drew its Scriptures, liturgy, and moral vision from Judaism, even as it proclaimed the New Covenant established in Christ — the fulfillment of Jeremiah’s promise of a covenant written on the heart, sealed in the blood of Jesus, and offering forgiveness and transformation to all who believe.

When Christians use the term “Judeo-Christian,” they affirm continuity — that the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob is the same God revealed in Jesus Christ. The phrase also highlights shared ethical commitments, such as the sanctity of life, justice, compassion for the poor, and the dignity of work, which have shaped Western civilization.

This heritage also explains why many Christians express solidarity with the Jewish people and support for Israel. While Christianity and Judaism diverge in their understanding of Jesus as Messiah, Christians nevertheless honor Israel’s role as God’s covenant people and see in them the roots of their own faith. For some, this connection is not only historical but also prophetic, tied to God’s ongoing purposes for Israel. Thus, the Judeo-Christian tradition is more than a cultural phrase — it represents a living bond between two faiths that share Scripture, history, and hope.

The New Testament

The Gospels — Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John — stand at the heart of the New Testament. Each one offers a distinctive portrait of Jesus. Matthew emphasizes Jesus as the fulfillment of Old Testament prophecy, Mark presents a fast-paced account of His ministry, Luke highlights compassion for the marginalized, and John portrays Jesus as the eternal Word made flesh.

While critics sometimes note variations among the Gospel accounts, Christians see these differences as complementary perspectives rather than contradictions — much like multiple witnesses to the same event. The sheer number of manuscript copies, their closeness to the originals, and their consistency across centuries provide strong evidence of accuracy. Yet, faith still plays a role: Christians acknowledge that understanding how divine sovereignty and human authorship blend is part of the mystery left for the “Why Line.”

The Acts of the Apostles continues the story, tracing the Spirit-empowered spread of the church from Jerusalem to Rome. Its historical details align with known geography, customs, and Roman administration, lending confidence in its reliability. At the same time, it reminds believers that the work of the Spirit often exceeds human explanation.

The Epistles provide pastoral and theological guidance, shaping doctrine and practice. Their survival across centuries and wide circulation among early Christian communities speak to their authenticity. Still, Christians accept that some teachings, like the relationship between divine sovereignty and human choice, will only be fully understood in eternity.

Revelation: The Consummation of God’s Story

The New Testament concludes with the Book of Revelation, a work unlike any other in the biblical canon. Written by the Apostle John while in exile on the island of Patmos, Revelation is both a pastoral letter to persecuted churches and a sweeping vision of cosmic conflict and ultimate victory. Its opening chapters contain messages to seven churches in Asia Minor, urging faithfulness amid suffering and compromise. These letters ground the book’s apocalyptic visions in real communities, reminding readers that Revelation is not mere speculation about the future but a call to perseverance in the present.

Revelation is filled with vivid imagery: beasts rising from the sea, trumpets sounding, bowls of wrath poured out, and a radiant city descending from heaven. These symbols draw heavily on Old Testament prophecy — echoes of Daniel, Ezekiel, Isaiah, and Zechariah run throughout the text. Rather than providing a literal timetable of end-time events, Revelation uses this imagery to unveil spiritual realities. The word “apocalypse” itself means “unveiling.” What John unveils is the deeper truth that behind political powers, wars, and persecutions lies a spiritual battle between the Lamb who was slain and the forces of evil.

Central to Revelation is the vision of Christ as the triumphant Lamb. Though slain, He is victorious, and by His blood people from every tribe and nation are redeemed. This paradox — victory through sacrifice — is the heart of Christian hope. The book shows that worldly empires may rage, false prophets may deceive, and persecution may intensify, but Christ reigns sovereign. The throne room vision in chapters 4 and 5 pulls back the curtain on history to reveal that God, not Rome or any earthly power, sits at the center of the universe.

Revelation also portrays the judgment of evil. Babylon, the symbol of corrupt power and idolatry, is cast down. The dragon, representing Satan, is defeated. Death and Hades are thrown into the lake of fire. These images remind believers that evil, though real and destructive, is not eternal. God’s justice will prevail, even if its timing is hidden from human sight. For many Christians, the exact details of how and when these events occur belong to the “Why Line” — mysteries entrusted to God until eternity clarifies them.

The climax of Revelation is its vision of new creation. In the final chapters, John sees a new heaven and a new earth, where the holy city, the New Jerusalem, descends like a bride adorned for her husband. Here God dwells with humanity, wiping away every tear, and abolishing death, mourning, and pain. The imagery returns readers to the garden of Genesis, now transformed into a city where the river of life flows and the tree of life bears fruit for the healing of nations. The Bible’s story, which began with creation and was marred by sin, concludes with re-creation and eternal communion with God.

For Christians, Revelation offers both warning and comfort. It warns against complacency, idolatry, and compromise with worldly powers, while comforting believers with the assurance that Christ is victorious and that suffering will give way to glory. While debates about millennial timelines, rapture theories, and symbolic details have divided interpreters, the central message remains clear: God is sovereign, Christ has triumphed, and the faithful are called to endure with hope.

Revelation continues to speak powerfully to the modern church. In a world marked by war, corruption, persecution, and uncertainty, its message of hope remains as relevant as ever. Believers under oppressive regimes find courage in its assurance that earthly empires do not have the last word. Christians navigating cultural pressure are reminded, like the seven churches of Asia, to hold fast to truth and resist compromise. Even in prosperous societies, Revelation warns against complacency and lukewarm faith. Most of all, it reassures every generation that history is not spiraling out of control but moving toward God’s promised renewal. For the church today, Revelation calls for perseverance, purity, and trust in Christ’s ultimate victory — a hope that sustains the faithful until the day when the “Why Line” is finally crossed and God’s purposes are made fully known.

Literary Diversity

Across these divisions, the Bible reveals itself as a rich tapestry of literary forms. Historical narratives, poetry, laws, parables, letters, and visions each serve unique purposes. The diversity of style strengthens rather than weakens the Bible’s credibility, demonstrating that its inspiration spans genres and cultures while still carrying a unified message.

Theological Core

Through all its varied voices, the Bible tells a single story: creation, fall, covenant, Christ, church, and consummation. At points this story confronts human understanding with mysteries — how God’s sovereignty works with human freedom, why suffering persists, or how eternity will unfold. Christians hold that such questions belong to faith, trusting that the God who inspired Scripture will one day supply answers.

Practical Application

Because of its varied content and structure, the Bible speaks to every dimension of human life. The Torah calls for obedience, the Prophets demand justice, the Writings shape worship and wisdom, the Gospels reveal Christ, the Epistles guide the church, and Revelation instills hope. Believers live with confidence in the reliability of God’s Word, while also acknowledging that some matters remain beyond comprehension — entrusted to God until the “Why Line” is crossed in eternity.

Cultural Influence

The Bible’s influence extends beyond the boundaries of faith communities. Its stories and phrases have seeped into common speech — “the powers that be,” “the writing on the wall,” “by the skin of your teeth.” Its themes have inspired the greatest achievements of Western art and music, from Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam to Handel’s Messiah. Its moral vision has informed legal systems, human rights movements, and social reforms.

At times, its words have been misused to defend injustice, but they have also served as rallying cries for freedom and equality, from the abolition of slavery to the civil rights movement. The Bible’s cultural legacy demonstrates its unique power to speak to the human condition across time and space.

Conclusion

To explore the Bible is to encounter both unity and diversity. Its structure — Torah, Prophets, Writings, Gospels, Acts, Epistles, and Revelation — provides the framework for God’s grand story. Within this structure lie literary beauty, theological depth, practical wisdom, and cultural influence.

For Christians, the Bible is more than history or literature; it is the inspired, infallible Word of God. It is accurate in its transmission, reliable in its message, and enduring in its truth. At the same time, it calls for faith — faith that accepts both what is clear and what remains a mystery for the “Why Line” in Heaven.

The Bible is a historical witness, a literary masterpiece, a theological anchor, an ethical guide, and a cultural fountainhead. Above all, it is the living Word of God that continues to speak, comfort, challenge, and transform.

Notes:

(1) The Dead Sea Scrolls were discovered between 1946 and 1956 in a series of caves near Qumran, on the northwest shore of the Dead Sea in modern-day Israel.

- The first discovery came in late 1946 or early 1947, when Bedouin shepherds stumbled upon clay jars containing scrolls.

- Over the next decade, archaeologists and local tribesmen uncovered 11 caves with thousands of fragments.

- In total, the scrolls represent about 900 different manuscripts, including portions of nearly every book of the Hebrew Bible (except Esther), as well as sectarian writings from the Jewish community that lived there.

These texts are dated from about 250 BC to AD 70, making them the oldest surviving biblical manuscripts, and they confirm the remarkable consistency of Scripture over centuries of transmission.

(2) The Process of Canonization: Canon comes from the Greek word kanōn, meaning “rule” or “measuring rod.” In the context of Scripture, it refers to the official list of books recognized as inspired and authoritative for faith and practice.

1. Old Testament / Hebrew Bible

- Torah (Pentateuch): The first five books were accepted earliest. By the time of Ezra (5th century BC), the Law of Moses was already authoritative.

- Prophets: Historical books (Joshua–Kings) and prophetic writings were recognized as Scripture by around the 2nd century BC.

- Writings: Books like Psalms, Proverbs, and Chronicles were accepted later. By the end of the 1st century AD (around the time of the Jewish Council at Jamnia, c. AD 90), the Hebrew Bible was essentially fixed.

- Criteria: Books were accepted if they had recognized prophetic or divine authority, were consistent with the Torah, and were widely used in worship.

2. New Testament

- Early Use: By the end of the 1st century, Paul’s letters and the four Gospels were already circulating among churches. Early Christians read them alongside the Hebrew Scriptures.

- Apostolic Authority: Writings had to be connected to the apostles or their close companions (e.g., Luke with Paul, Mark with Peter).

- Orthodoxy: The teaching had to align with the “rule of faith” — the core message of Jesus’s life, death, and resurrection.

- Widespread Use: Books accepted and read across many churches carried more weight than local or sectarian texts.

- Recognition, not Selection: Early councils did not “create” the canon but confirmed what was already being used and recognized as inspired.

3. Key Milestones

- By AD 170, the Muratorian Fragment lists most New Testament books.

- By the 4th century, church councils (Hippo in 393 and Carthage in 397) confirmed the 27 books of the New Testament we know today.

- The canon was recognized by both usage and consensus — seen not as human invention, but as God’s providence guiding the church.

📖 Summary:

The canonization process was organic and Spirit-led, unfolding over centuries. The Bible wasn’t “invented” at a council but recognized as Scripture because the people of God had already experienced these writings as the inspired Word.