Inspired by Dan Johnson, Written by AI, Guided and Edited by Lewis McLain

I. Hermann Hesse: Life and Vision

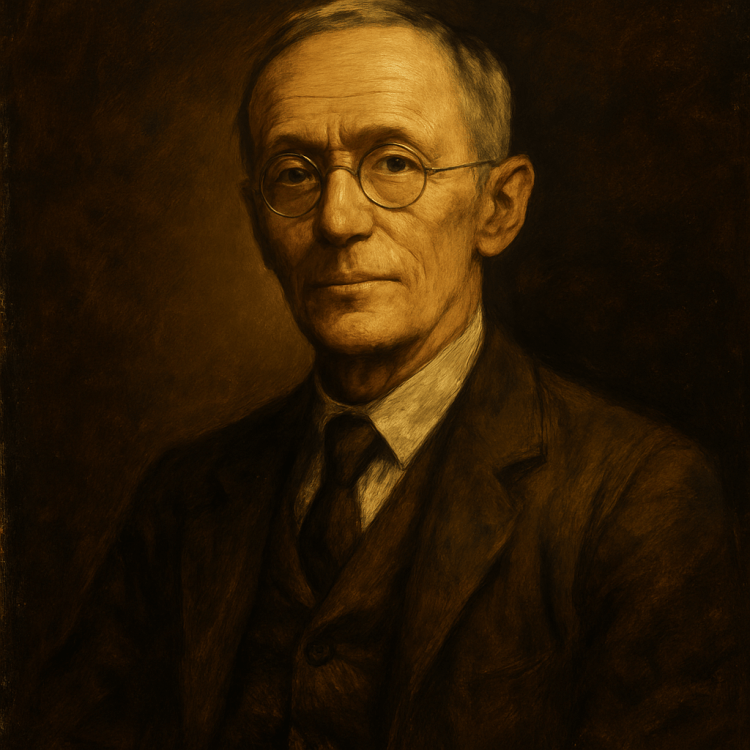

Hermann Hesse (1877–1962) was one of the twentieth century’s most influential literary figures, a seeker whose novels became guideposts for millions navigating the crises of modernity. Born in Calw, in the Black Forest of Germany, Hesse was the son of Christian missionaries. His childhood was steeped in pietism and biblical devotion, but also in conflict—he struggled against the rigidity of his family’s expectations and endured mental health crises that shaped his outlook. When I read many of his books, there were two recurring personal notes in his diaries: he had bad eyesight and complained about how much his eyes hurt. He also traded letters with friends that include small water paintings sent and received. Those pictures seemed to be pleasing to Hesse. If you start seeing pictures (with the help of AI), my motivation comes from Mr. Hesse. LFM

For Hesse, writing was both therapy and spiritual exploration. His early novels reflected the tensions of his life: the desire for freedom against the weight of tradition, the search for authenticity in a rapidly industrializing world.

- In Demian (1919), Hesse explored inner duality, freedom, and the necessity of self-discovery beyond societal norms.

- In Siddhartha (1922), he imagined a man’s journey to enlightenment in ancient India, fusing Western existential doubt with Eastern philosophy.

- In Steppenwolf (1927), he dramatized the loneliness of the modern intellectual and the quest for transcendence amid despair.

- In The Glass Bead Game (1943), his Nobel Prize–winning masterpiece, he conjured a future order devoted to the synthesis of knowledge, beauty, and spirituality.

Amid these great novels stands a shorter but profoundly symbolic tale: The Journey to the East (1932). Though brief, it contains one of Hesse’s most enduring insights—leadership is not power, but service.

II. The Journey to the East: The Servant and the Master

The novella tells the story of a secret brotherhood called the League, a timeless spiritual fellowship that undertakes a pilgrimage “to the East.” The East is never fully defined—it is both place and symbol, representing wisdom, transcendence, and the fulfillment of human longing.

The narrator, H.H., joins the League’s pilgrimage. Along the way he describes a mysterious assortment of travelers: historical figures, literary characters, and seekers from all walks of life. The journey unites them in pursuit of a higher goal.

Yet the true heart of the story is a man named Leo. Leo appears to be nothing more than a cheerful servant. He tends to the pilgrims, carries their bags, prepares their meals, and sings songs that lift their spirits. He is ordinary, unnoticed—yet indispensable.

Then one day Leo disappears. Without him, the pilgrims falter. Discord and division creep in, and the League dissolves. H.H. falls into despair, convinced the journey has failed.

Years later, in a twist of revelation, H.H. learns the truth: Leo was not simply a servant. He was in fact a leader of the League, the embodiment of the very wisdom the pilgrims were seeking. The pilgrimage fell apart because the group failed to recognize that true leadership had been in their midst all along.

Hesse’s parable is at once mystical and practical: it insists that authentic leadership flows not from domination but from humble service. In the inversion of roles—servant as master, master as servant—Hesse revealed a paradox at the heart of human community.

III. Robert Greenleaf and the Birth of Servant Leadership

Decades later, in the United States, Robert K. Greenleaf (1904–1990), an executive at AT&T, was searching for a new way to understand leadership. He had witnessed firsthand how corporate hierarchies often crushed initiative, fostered fear, and alienated workers. After 40 years in management, he turned to teaching and writing, determined to challenge the prevailing model of top-down authority.

In the 1950s, Greenleaf read The Journey to the East, and Leo’s example struck him like lightning. Here was the vision he had been seeking: the leader is great not because of command but because of service. Out of this insight, he developed the philosophy he called servant leadership.

In his seminal 1970 essay, The Servant as Leader, Greenleaf wrote:

“The servant-leader is servant first… It begins with the natural feeling that one wants to serve, to serve first. Then conscious choice brings one to aspire to lead. The difference manifests itself in the care taken to make sure that other people’s highest priority needs are being served.”

Greenleaf’s framework reshaped modern leadership thinking. He identified qualities that distinguish servant leaders:

- Listening and Empathy – Understanding others deeply before acting.

- Awareness and Foresight – Seeing beyond immediate demands to future consequences.

- Healing and Stewardship – Caring for individuals and institutions as trust, not possessions.

- Commitment to Growth – Helping others become wiser, healthier, and freer.

- Building Community – Nurturing belonging, not simply extracting productivity.

Unlike traditional leadership, which seeks power to direct, servant leadership seeks responsibility to care. Greenleaf insisted that the true test of leadership was not organizational success but human flourishing: “Do those served grow as persons?”

IV. Servant Leadership in Today’s World

Although Greenleaf’s vision emerged from corporate disillusionment, servant leadership has spread far beyond the boardroom. Its influence can be traced across diverse spheres today:

1. Faith-Based Institutions

- Many Christian organizations and seminaries explicitly teach servant leadership, grounding it in the life of Jesus.

- Pope Francis has often invoked its spirit, urging leaders to be “shepherds who smell of the sheep.”

- Evangelical colleges and Catholic universities alike offer leadership courses built around Greenleaf’s principles.

2. Education

- Universities such as Gonzaga, Indiana Wesleyan, and Regent have made servant leadership central to their leadership programs.

- In secular contexts, “inclusive leadership” and “transformational leadership” often echo servant leadership’s core values of empathy and empowerment.

3. Healthcare and Caring Professions

- Hospitals and nursing schools apply servant leadership to patient-centered care.

- Nursing theory highlights Greenleaf’s ideas of empathy and stewardship as essential to healing.

- Systems like Cleveland Clinic and Mayo Clinic promote leadership cultures rooted in service.

4. Nonprofits and Social Enterprises

- Global NGOs like Habitat for Humanity and World Vision emphasize leadership through service to the vulnerable.

- Social entrepreneurs adopt servant leadership as a model for organizations aimed at social good.

5. Business

- Southwest Airlines and TDIndustries are classic case studies of servant leadership cultures in practice.

- The rise of “conscious capitalism” and stakeholder-driven business models reflects a growing embrace of servant-leadership values.

6. Military and Public Service

- Though hierarchical, parts of the U.S. military stress servant leadership: officers as stewards of their soldiers’ welfare.

- Police and fire departments in some communities incorporate the philosophy for community trust.

7. Global Reach

- In Africa, servant leadership resonates with Ubuntu (“I am because we are”), highlighting shared humanity.

- In Asia, it has influenced leadership practices in Singapore and the Philippines, where communal values are strong.

- In Scandinavia, egalitarian management structures mirror Greenleaf’s call for humility and shared responsibility.

In today’s world of political polarization, corporate scandals, and institutional mistrust, servant leadership remains both countercultural and urgently relevant. Where command-and-control leadership often falters, servant leadership builds trust, resilience, and long-term sustainability.

V. Conclusion: The Servant as the True Leader

Hermann Hesse, writing in a fractured Europe, offered a parable of a servant who was secretly a master. Robert Greenleaf, confronting the failures of mid-century corporate America, found in that story the spark for a radical rethinking of leadership.

Together, they remind us that the deepest authority is not rooted in command but in service. Leadership is not the pursuit of followers but the care of souls. Institutions endure not because of power structures but because of communities sustained by humility, empathy, and stewardship.

In an age that often celebrates strength as dominance, Hesse and Greenleaf point to another way: that the one who carries the bags may in fact be the one who carries the truth.